Super Mario Land: The Brilliance of an Underrated Classic

The Game Boy’s Super Mario Land is sometimes regarded as an oddity today. We argue that it’s actually a bit of a classic...

In 1947, a 60-something-year-old American named George Adamski took the first of several photos of what he claimed was a Venusian Scout Ship – a mysterious craft from another world. The images were widely printed in newspapers and magazines, and the ship depicted in them – saucer-shaped, with a domed roof and round windows – did much to define the look of unidentified flying objects at the height of the ’40s and ’50s UFO flap.

More than four decades later, Adamski’s flying saucers landed in a highly unexpected venue: Super Mario Land. Right at the start of world 2-1, there’s one hovering right in the middle of the screen, with its round portholes, unmistakable shape – like a dustbin lid – and familiar bulbous “landing gear” jutting out of the bottom. It seemed desperately strange then, and strange now, that Nintendo’s flagship action franchise would delve into the further reaches of Ufology – but then again, it was all par for the course in a game that also features Egyptian pyramids, giant Maoi heads from Easter Island, and undersea levels where flying saucers sit on the ocean floor.

It was as though, in their desire to find a new theme for Mario’s first proper handheld platformer outing (forgetting those simplistic Game & Watch titles earlier in the decade), Nintendo turned to the oddball ideas of author Erich Von Daniken, who posited that everything from the ancient pyramids to bananas were somehow connected to alien visitations. At the time, Super Mario Land sold millions of copies, and along with Tetris, was one of the Game Boy’s must-have titles. But if later critiques of Super Mario Land are anything to go by, it’s generally regarded as an aberration – an ill-formed semi-sequel that doesn’t deserve to be mentioned in the same breath as the franchise’s mainline titles from around the period, like Super Mario Bros. 3 or Super Mario World. Eurogamer’s Chris Schilling, in his retrospective, regarded the game as an act of in-house rebellion, if not outright sabotage.

It’s important, however, to look at Super Mario Land in its late-80s context. In 1989, the rules of the Super Mario universe, if we can call it that, were still in flux – especially in the west. Super Mario 2, famously a reworking of an entirely different game called Doki Doki Panic, had only come out in America the previous year, and wouldn’t emerge in Europe until April 1989. It mixed up the Super Mario Bros. playbook with a throwing mechanic, a range of playable characters, and a vague Arabian Nights theme (something established in Doki Doki Panic, and simply carried over in the reskinned game). Super Mario Bros. 3 and Super Mario World, which would do much to build on the visual richness of the franchise, were still many months away.

Further Reading: Why Mario Bros. Is Nintendo’s 1983 Arcade Classic

As far as Nintendo was concerned, then, the Super Mario brand of running, jumping, and hitting blocks was still open to reinterpretation – especially with the imminent launch of the Game Boy, which effectively opened up a largely unexplored vista for the entire games industry. Before the Game Boy, there had never really been a system like it before – not one capable of running relatively complex games on swappable cartridges, like a Nintendo Entertainment System on the move. Who even knew what the console’s prospective customers would even want from the new device? Would they even want to play a game with the speed and relative complexity of Super Mario Bros., or would they prefer something more akin to a Game & Watch game? That untested market, coupled with the Game Boy’s technical limitations, such as its ferociously blurry LCD screen, must have made Nintendo a little wary – little wonder, then, that a relatively new title like Tetris was chosen as the pack-in game, and not the firm’s plucky little mascot.

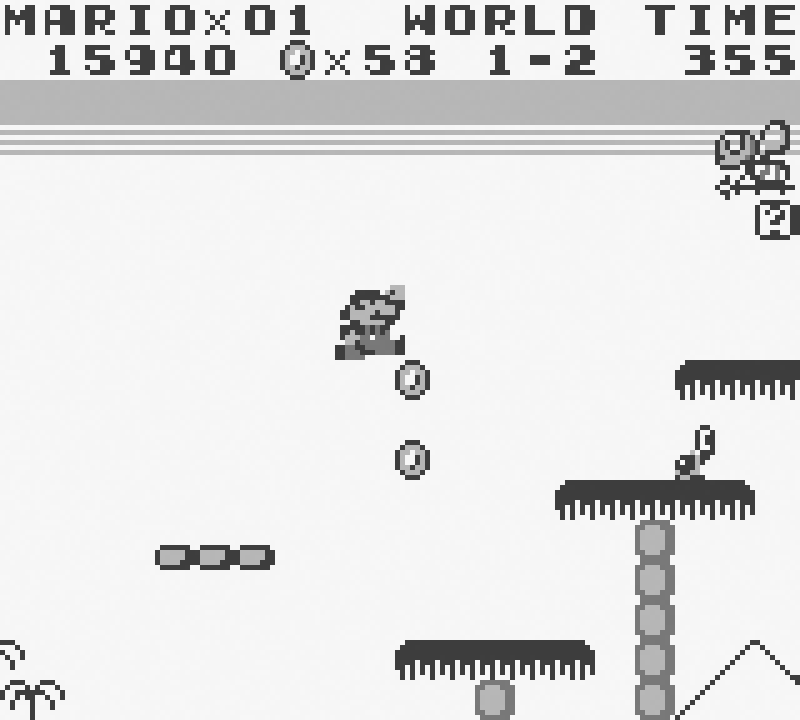

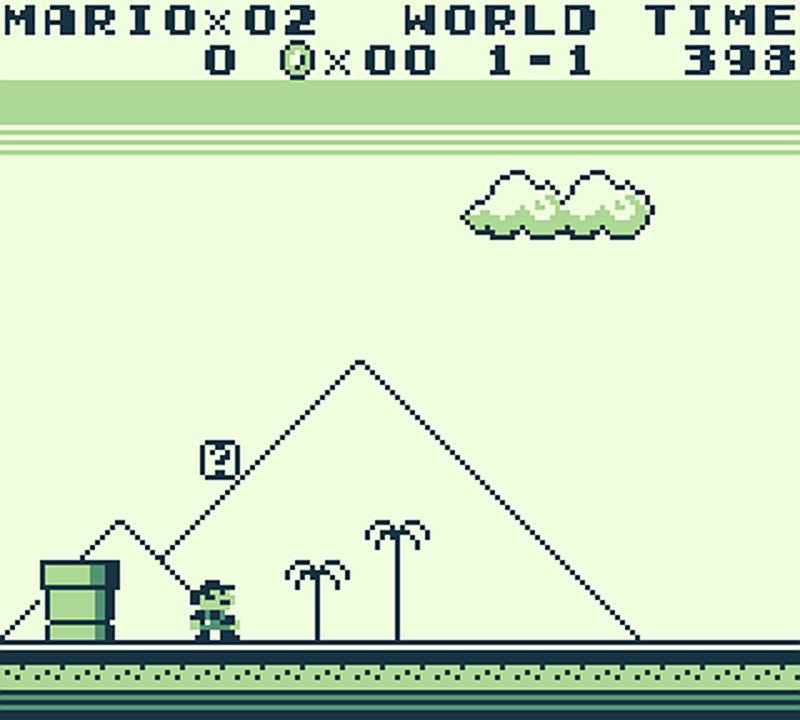

With all that in mind, Nintendo’s decision making when it came to Super Mario Land was pretty sensible. In shrinking the game for the handheld’s tiny screen, shortcuts were made to keep the visuals clean and simple – the backgrounds left largely white, with the occasional outline of a pyramid or cloud to suggest the location. Goombas are now tiny silhouettes with white eyes, life-up tokens are now little hearts, and Mario fires bouncing spheres rather than gobs of flame. With those sensible choices came some daring and downright weird ones. The platforming levels are very occasionally interspersed with scrolling shooter stages, where Mario clambers into a vehicle (a submarine in one, a plane in the other) and blasts away at floating enemies. The flagpole bit at the end of the platform stages in Super Mario Bros. is replaced by a challenge that involves reaching a higher door, which in turn launches a bonus mini-game where the player earns extra lives. And then there are the very strange world designs, with all those UFOs and giant heads…

A quick glance at Super Mario Land’s personnel explains why the game doesn’t quite fit the established mold. Shigeru Miyamoto, the design legend behind the other Mario games, had nothing to do with this one. Instead, the project was headed up by Gunpei Yokoi, a design genius whose ideas did much to shape Nintendo’s status as a video game giant. Beneath him was director Satoru Okada, best known for his work on Metroid and Kid Icarus, but who’d never been involved in a Mario game before. Between them, Yokoi and Okada cooked up a world that is very consciously separate from the Mushroom Kingdom of the main console titles. The setting here is somewhere called Sarasaland, the damsel in distress is Princess Daisy rather than Princess Peach, and the main villain is an alien named Tatanga, and not Koopa.

Further Reading: Super Mario Bros. Platformers Ranked

All these changes – and many more, which we’ll get to shortly – could certainly be interpreted as a willful bit of subversion, but there’s also an alternate possibility. As mentioned above, Nintendo was testing new ground with the Game Boy, and in 1989, there was still no telling how well – or how badly – the machine would be received. That the system needed a Mario game was an edict handed down from the company’s CEO, and the hero’s smiling face certainly would’ve helped potential customers come to terms with the new-fangled Game Boy. But at the same time, Nintendo may have wanted to keep a certain distance between Mario on the NES and Mario on the Game Boy – not to mention the Super NES, just around the corner, which had its own killer app (Miyamoto’s Super Mario World) deep in development. If the Game Boy failed, then the Super Mario brand ran the risk of being tarnished along with it. It was far better to create a title that felt detachable and fairly standalone from the main franchise. If the thing failed to sell, Nintendo could at least dismiss Super Mario Land as a fun spin-off, or a dream Mario once had after eating too much cheese.

If Nintendo was being protective of the Super Mario brand, though, Yokoi and Okada used the opportunity to change things up. Some of the changes are interesting or infuriating depending on which way you look at them. At first glance, the tiny turtle-like enemies just look like regular Koopa Troopas. It’s only when you bounce on them that you learn their shells are actually explosive and will kill Mario if he’s standing too close when they go off. Given that one of the central mechanics in Super Mario Bros. involved booting empty Koopa shells at enemies, this could be regarded as trolling on Nintendo’s part. At the very least, it’s a non-verbal means of telling the player, “You’re not in the Mushroom Kingdom anymore.”

Subtle changes have also been made to Mario’s movement and jumping physics, while the bouncing balls refuse to behave quite like the fireballs in his previous adventures. When fired, they hit the ground fairly close to Mario’s feet, which means that he has to get quite close to enemies to destroy them – particularly dangerous when it comes to the fast-moving Fly creatures, which take two bouncing balls to kill. Floating Easter Island head enemies are even trickier – they take three hits to kill, and will follow Mario to the ends of the earth if he tries to ignore them.

Further Reading: 10 Remarkable Facts About the Super Mario Bros. Movie

None of this is to say that Super Mario Land is a particularly tough game. With just 12 short levels spread over four worlds, it can still be completed in short order. Nevertheless, Super Mario Land feels absolutely right for the diminutive Game Boy – the lesser difficulty level helps defuse the frustration caused by the system’s smeary screen, and the challenge ultimately comes not from simply getting to the end, which is easily done, but by finding every possible secret area, collecting every coin, and beating your own high-score.

Besides, Super Mario Land is scored to one of the best theme tunes in Mario history – a jolly, up-tempo suite of chiptunes composed by Hirozaku Tanaka that could have easily graced one of the main console sequels. Once heard, it echoes in the brain for days, like one of Mario’s bouncing balls. The music’s a reminder of how successfully Yokoi’s team succeeded in creating a remarkably Mario-like experience on such a tiny scale. Sure, the sprites are absurdly small, but Mario himself is immediately recognizable, and he even grows to a subtly different size when he collects a mushroom, in grand Super Mario Bros. tradition.

The “same, but smaller” ethos stretches to the levels themselves. They may be short, but they have all the secret rooms accessed through pipes, coins, mystery boxes, and enemies to squash as you’d expect, and each world has its own boss at the end, each defeated in its own way (the first can be offed by hitting a switch, not unlike the King Koopa confrontations in Super Mario Bros.). As weird as the backgrounds are, they work perfectly for the Game Boy: the interior of a pyramid is sketched in with simple black hieroglyphs, each one just a handful of pixels high. Some dinky flickering candles complete the effect.

Yes, it’s all incredibly weird, but the Von Daniken-like aesthetic feels somehow in keeping with a series of games that has been decidedly dreamlike from the beginning – the whole notion of magic mushrooms granting greater size is, after all, taken from Alice in Wonderland.

If the franchise’s history after Super Mario Land tells us anything, though, it’s that Nintendo wasn’t all that impressed by what emerged in 1989. Mario never revisited Sarasaland in later games. No other entry attempted a side-scrolling shooter level. The sequel, subtitled Six Golden Coins, looked entirely different, with chunkier, zoomed-in graphics and even a new villain – Wario, who made his debut in that game. Super Mario Land’s alien boss, Tatanga, presumably burned up on the way back to his home planet.

Further Reading: 25 Underrated NES Games

Super Mario Land stands alone to a degree, but it’s fascinating to see how well it holds up almost three decades later. Play the thing on the 3DS, or even on a SNES through Nintendo’s Game Boy cartridge adapter, and the screen blur vanishes, and those curious level designs shine all the more brightly. It’s a simplistic game, but consistently entertaining – its ideas and sudden switches of style and theme providing plenty of surprises the first time around, and the assorted hidden coins and lives adding at least a bit of longevity.

Super Mario Land also has more in common with 2017’s Super Mario Odyssey than even Nintendo may have realized – the same harebrained lurch from one scenario to another (pyramids and Mexican hats, dinosaurs, rabbits on the moon, etc.), the same approachable difficulty level, and the same apparent desire to tinker with existing Mario mechanics. With the console-handheld hybrid Switch, and following the relative failure of the Wii U, Nintendo again found itself going for broke – which may partly explain the vague similarities between two games divided by such a huge expanse of time.

It’s possible we’ll never know exactly why Super Mario Land’s creators put one of Adamski’s flying saucers in their game, but we can’t help thinking it’s an apt image for an odd, now very old entry in the Mario franchise. Years after he took his photos, it emerged that Adamski’s “Venusian Scout Ship” was simply the shade from a medical lamp – the spherical landing gear underneath were lightbulbs, hurriedly secured into position.

Super Mario Land, similarly, is a curious beast, its style built up from bits and pieces all strapped together. But just as Adamski managed to create a semi-iconic UFO from bric-a-brac found in his garage, so Super Mario Land’s makers took some disparate ideas seemingly at random and, somehow, created a weird but deeply lovable handheld classic.