How Xena: Warrior Princess used Greek Myth

Xena: Warrior Princess had a rich fantasy world of its own, but drew heavily on Greek mythology in imaginative and exciting ways.

First of all, sorry if this bursts anyone’s bubble, but sadly Xena: Warrior Princess is not a ‘real’ character from Greek myth. Whereas Hercules and Iolaus from Hercules: The Legendary Journeys are both important characters from Greek mythology, the three most important characters in Xena: Warrior Princess – Xena, Gabrielle, and Callisto – are all original characters with entirely original stories.

Xena does have things in common with some characters from Greek myth. Most obviously, the Amazons (who appear in the series and adopt Gabrielle as their princess, but Xena is not one of them) are a ‘real’ Greek myth – not a real people, but a mythical tribe who appear in numerous stories from Greek mythology. They were described as a tribe of warrior women, who cut off one breast to make it easier to shoot arrows – oddly enough, the show left out that detail!

The closest non-Amazon character to Xena is probably Atalanta, a huntress who killed centaurs with arrows (with both breasts intact), won a wrestling match against the male hero Peleus, and refused to marry until a suitor could beat her in a foot race, which no one was able to do without cheating. The goddesses Artemis and Athena, who both appear in the series, had traditionally masculine attributes as well, and Athena is especially similar to Xena as she was associated with war (as well as the male god of war, Ares), but they were both completely divine beings, and so were considered a bit different to mortal human women.

Keeping it real

The series did include lots of elements from ‘real’ Greek mythology. Numerous Greek gods and goddesses turned up over the course of the show, from famous Olympians like Ares, Zeus, and Aphrodite, to less well known deities like Nemesis (goddess of justice), Morpheus (god of dreams), and Discord (in Greek Eris, the goddess of discord). Some early episodes were inspired by stories from Greek myth, like Hercules freeing the Titan Prometheus from being chained up and having his magically regenerating liver eaten by a giant eagle every day (Season 1’s ‘Prometheus’); the story of Odysseus, known by his Latin name Ulysses in the show, and his long journey home to his wife Penelope (Season 2’s ‘Ulysses’), and Season 1’s brief glimpse of the Trojan War in ‘Beware Greeks Bearing Gifts’.

For the most part, rather than directly adapting specific myths, the series used characters, elements and ideas from Greek mythology to create new stories. As a 1990s show, the series used the blend of arc plotting and standalone episodes that was common at the time. This meant that the show, like an anthology show, could do different types of stories in different episodes, allowing it to incorporate not just the tragic and dramatic tone of some Greek myths, but the comedic and light-hearted tone of others as well – for in the ancient world, playwrights used mythological characters and themes for both tragedy and comedy.

Ancient Greek playwrights would mess around with the stories people thought they knew to surprise their audience and keep their attention. The famous story of the witch Medea murdering her own children, for example, was an innovation of the playwright Euripides, adapting earlier stories where they were killed by accident or killed by other characters. So what Xena (and parent show Hercules: The Legendary Journeys) was doing was exactly what ancient Greek dramatists did, taking ideas and characters people know and playing around with them to create something new.

Remixing the myths

One of the interesting things about Xena: Warrior Princess was the way the show took place in a vaguely described mythical time which seemed to cover millennia of not just Greek mythology and legend, but even well-known, real and dateable Roman history. For the ancient Greeks and Romans, there was a sense that the distant past was a time of myths, and that gods and heroes and monsters walked the earth long before their own time. However, they also had a fairly strong sense of there being a rough chronology to these stories. Certain myths happened in a certain order, and there was a clear progression of ‘Ages’ with different events belonging to different periods. The Titan Kronos was in charge first, then he was usurped by his son Zeus. Mankind was created by the Titan Prometheus, and Woman inflicted on them as a punishment to Prometheus by Zeus (ancient Greek myth was not as feminist as the show it inspired, as you can tell!).

The Greek poet Hesiod outlined five Ages of Man. The Golden Age was the reign of Kronos, when men lived like gods. When Zeus took over, the Silver Age began, and men were now inferior beings who had to work for a living. The Bronze Age was an age of strong, warlike men who were destroyed by Deucalion’s flood (the Greek equivalent of the story of Noah’s Ark). Next was the Age of Heroes, and this is where myth starts to meet legend and pre-history. This is the period when the Trojan War supposedly took place – the war is fictional, but the city of Troy is real (it’s at a site called Hissarlik in modern Turkey) and so were the Greek city states described in the stories, so this war can be placed in a real timeline of human history, at around 1200 BCE, even if the war as described in the stories never really happened. The final age was the Age of Iron, Hesiod’s present day of around 700 BCE, an era of misery and toil (Hesiod was not much of an optimist).

Xena throws all of this chronology out of the window and blends everything together into a glorious mish-mash of myth, legend, and history. The 10-year Trojan War is covered in a single episode set at the end of the siege. Heroes from different stories appear in no particular order. King David of Israel turns up – he lived around 1010-970 BCE, which would be a couple of centuries after the Trojan War.

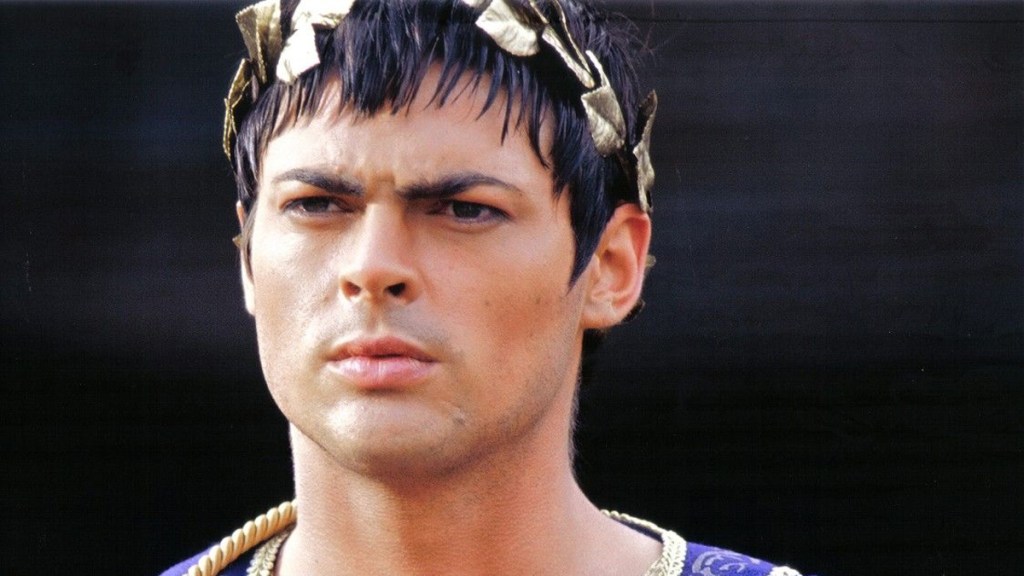

Most bizarrely for a show supposedly about Greek mythology, substantial chunks of Roman history are thrown into the mix as well, forming major story arcs across the years, especially in the fourth season. Producer Rob Tapert is obviously keen on this period because he later produced the STARZ Spartacus series – starring his wife, Lucy Lawless, a.k.a Xena – which features several of the same characters including Julius Caesar, Crassus and (briefly) Pompey.

Even when using real historical characters, though, Xena folded in decades’ worth of history. Most of the characters and loosely adapted plotlines follow the collapse of the Roman Republic and the beginning of a monarchy under the emperors in the first century BCE, and although it’s loosely adapted to say the least, there are lots of genuine details. Julius Caesar really was kidnapped by pirates as a young man (and had them all executed later on) and the power struggles in the dying years of the Republic really did feature an alliance between Crassus, Caesar, and Pompey, and the famous love affair between Mark Antony and Cleopatra. The British Queen Boudicca, or Boadicea, however, lived over a hundred years later, and although Julius Caesar invaded Britain twice, he never actually conquered it (it was the later emperor Claudius who did that) so even the Roman historical chronology is all over the place.

There’s something kind of wonderful about this ‘throw everything at the wall and see what sticks’ approach to chronology. There are lots of fun depictions of Julius Caesar in pop culture (from the dude with the surfer hairdo in Tapert’s Spartacus: War of the Damned to Kenneth Williams camping it up in Carry on Cleo) but none are quite as off-beat as Karl Urban repeatedly trying to kill Xena and even escaping the underworld after death to create a new reality where she never met Gabrielle, in an attempt to save himself. And the idea that the first Empress and possible serial killer (depending which ancient Roman rumours you believe) Livia was really Xena’s daughter – and a formidable warrior – is rather fun too.

Playing in other cultures’ sandpits

It wasn’t just time that Xena jumbled up whenever the writers felt like it – the series also included plenty of gods, myths and heroes from other places that had nothing to do with Greece or Rome. From Norse gods (including Loki and Odin) to Hindu gods, to Tau Chinese characters, to the early medieval British hero Beowulf, Xena’s “time of ancient gods, warlords, and kings” and “land in turmoil” could be anywhere, anywhen. This gave the writers great freedom in choosing the stories they wanted to tell and playing with them in new and creative ways, as well as allowing them to cast a diverse group of actors to play them.

Casting black actresses Galyn Gorg and Gina Torres as Helen of Troy and Cleopatra respectively was reflective of academic movements throughout the late 1980s and 1990s to recognise the importance of black Africans to Mediterranean culture, and it has been argued that the real Cleopatra was black, as while her ethnicity was primarily Greek (her Greek ancestors conquered Egypt), her grandmother was a concubine of unknown origin. But the wide range of sources of inspiration Xena drew on meant that they could largely cast actors suited to their roles, regardless of skin colour. Although the goddess of Love, Aphrodite, was somehow still portrayed as a slim, ditzy blonde in pink, which is not a representation the ancient Greeks would have recognised – their statues of Aphrodite are a lot more rounded in body shape and wear even less clothing!

Xena: Warrior Princess, like a lot of great shows from the 1990s, was a series full of good humour and creativity that didn’t take itself too seriously most of the time, but was still able to land a dramatic punch when it turned its mind to it. It’s a method of making television that, when done well, can give audiences the best of all worlds, and perhaps one that might see a bit of a comeback if audiences start to tire of heavily serialised, grimdark TV. The series’ approach to Greek mythology was like its approach to story-telling in general – use the things that you think will work, don’t be afraid to change things, to mix it up, to mess things around, and tell whatever story you want to tell using whatever tools are available to you to tell it. The ancient Greek playwrights would have been proud.