The Trial of the Chicago 7 Ending: What Happened Next?

We examine some of the events that happened next for the major players in The Trial of the Chicago 7 after the ending.

It’s a strangely feel-good finale. After spending more than two hours witnessing a gross miscarriage of justice that seemed to suggest the deck is stacked against those the establishment deems “radical” or “extreme,” Aaron Sorkin’s The Trial of the Chicago 7 ends with the smallest of victories being given Hollywood heft. Tom Hayden (Eddie Redmayne) is all but promised a lenient sentence by the vindictive, and potentially senile, Judge Julius Hoffman (Frank Langella), provided he offers a contrite statement before the court.

Instead Hayden attempts to read off the names of every American who died in Vietnam since this sham trial began. It’s a symbolic act of defiance, and a welcome one that sends the court into temporary pandemonium. It doesn’t change anything, other than maybe Hayden’s sentence, but the audience can savor the good fight against corrosive authority, so perfectly personified by Langella’s judge.

That’s all well and good, but what happened afterward? A handful of freeze frames and sentences worth of bite-sized information tells us a little bit of what came next for each major player in the trial, but not enough. So allow us to expand a bit.

Abbie Hoffman

As played with resounding cynicism by Sacha Baron Cohen, Aaron Sorkin’s Abbie Hoffman convincingly proves you can turn contempt for court into a religion. The actual Hoffman was a leader of the Yippie movement and later wrote Steal This Book, but his career extended beyond the courtroom and that literary subversion. Prior to being indicted for conspiracy to incite a riot across state lines, Hoffman was already a counterculture figure who cut his teeth as a member of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and organizing Liberty House in the fight for Civil Rights.

He became focused on the Vietnam War in the late ‘60s, but was never afraid of a good stunt, such as when he rained fake and real dollar bills down on the New York Stock Exchange in 1968. Some investors booed, others began filling their pockets with the green on the floor. Additionally, he had the notoriety of being chased off stage at Woodstock by Pete Townshend after he interrupted The Who’s set to demand the release of John Sinclair, co-founder of the anti-racist White Panther Party. This occurred about one month before the trial started.

After the trial, he built his fame with Steal This Book in 1971, which encouraged readers to find ways to live for free without paying for possessions. However, Hoffman soon disappeared from public life, becoming a fugitive after he was charged with intent to sell and distribute cocaine in 1973 (he claimed it was entrapment). In 1974, he had plastic surgery and began living by the name Barry Freed, until he turned himself into authorities in 1980—the same day his interview with Barbara Walters aired. He’d go on to stage civil disobedience to protest the CIA and Iran-Contra affair in 1986, and write Steal This Urine Test to protest the War on Drugs in 1987. He even appeared in Oliver Stone’s Born on the Fourth of July.

But suffering from Bipolar disorder, and depressed both by his mother’s cancer diagnosis and at the lack of protest in youth culture of the ‘80s, he eventually died by suicide when he swallowed 150 phenobarbital tablets with liquor in 1989. He was 52, and the FBI had a file on him that was over 13,000 pages long.

Tom Hayden

Prior to the Trial of the Chicago Seven, Tom Hayden became a national figure on the left for authoring the first draft of the Students for a Democratic Society’s political manifesto, the Port Huron Statement. In it Hayden advocated for, among other things, a “New Left” that pursued participatory democracy in the spirit of nonviolent civil disobedience, allowing citizens to directly vote on social issues. He also toured North Vietnam in 1965, later co-writing The Other Side with Staughton Lynd. The pair also disavowed the anti-Communism of their parents’ generation.

After the trial, Hayden returned to tour the conditions of North Vietnam multiple times, as well as in Cambodia and Laos as the Richard Nixon administration began bombing those regions. While Hayden did not meet movie star and future second wife Jane Fonda during her own infamous trip to Hanoi in 1972, the pair shared a drive to be politically active and motivate social change, including urgently ending the Vietnam War. Hayden and Fonda married in 1973, and collaborated on the 1974 documentary Introduction to the Enemy. During this time, he also founded the Indochina Peace Campaign, which Fonda would name her production company, IPC Films, after.

Hayden soon became more active in Democratic Party politics, advocating for strong environmental protection policies, beginning with an unsuccessful primary challenge against Democratic U.S. Senator John V. Tunney in 1976. He did, however, succeed in being elected to the California State Assembly for 10 years, beginning in 1982, and the California State Senate for eight years, beginning in 1992. He also ran unsuccessfully for governor in 1994 and Mayor of Los Angeles in 1997.

He and Fonda divorced in 1990, but he married again three years later. Hayden passed away in October 2016, but not before being one of the Democratic National Committee’s California representatives that year. He threw his support behind Hillary Clinton after initially saying he was leaning toward (but not endorsing) Bernie Sanders.

Jerry Rubin

As the other co-founder of the Yippies, Jerry Rubin’s early life shared many of the same values as Abbie Hoffman. After all, he dropped out of the University of California, Berkeley in 1964 to become a full-time social activist. In 1967 that included running for mayor of Berkeley and winning 20 percent of the vote on a platform of being anti-war, pro-Black Power, and wanting to legalize marijuana. That didn’t work out, but along with Hoffman, Rubin had better success in a number of publicity events, including the Stock Exchange demonstration events mentioned above, and when he appeared before the House Un-American Activities Committee dressed as a Revolutionary War soldier who quoted Thomas Jefferson and Thomas Paine while blowing soap bubbles at congressmen.

This contempt was an example of Rubin’s original worldview that television news mythologizes whatever it covers. “I’ve never seen ‘bad’ coverage of a demonstration. It makes no difference what they say about us. The picture is the story.”

Yet shortly after the trial, Rubin’s perspective changed. While during the early ‘70s he continued protesting, organizing demonstrations that would lay down before trucks transporting napalm, as well as attempting to organize protests at both the Republican and Democratic National Conventions of 1972, he became disgusted after Nixon was reelected that year. He retired from politics in the mid-‘70s to become an entrepreneur, making his first millions by being an early investor in Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak’s Apple Computer.

By 1980 Rubin was a full-fledged Wall Street stockbroker for John Muir & Co., and was organizing parties at Studio 54 via his own Business Networking Salons, Inc. company. He even took on a debate tour with old ally Abbie Hoffman in a series of events called “Yippie versus Yuppie.” Rubin claimed counterculture was too scary to affect real change and that “wealth creation is the real American revolution.” From George Washington-chic to Washington D.C. Brooks Brothers attire. He died in 1994 from a heart attack after being hit by a car in Los Angeles.

Bobby Seale

A co-founder of the Black Panther Party with Huey P. Newton, Seale was one of the most powerful voices for Black rights and Black Power in the late ‘60s—hence why the Justice Department dubiously charged Seale with conspiracy to incite a riot alongside the rest of the “Chicago Seven.” As demonstrated in the film, Judge Julius Hoffman grotesquely ordered Seale be gagged and beaten after denying Seale the right to legal counsel for months. While Seale was later severed from the trial, the Netflix film glosses over what exactly happened afterward to the Black Panther leader.

Seale indeed stood trial again in Connecticut in 1970 for the murder of Alex Rackley. Rackley was a 19-year-old Panther when he was tortured for two days at the New Haven Panther headquarters after being suspected of being an FBI informant. After days of interrogation and physical violence, Rackley confessed under duress. He was executed the next day. As a Black Panther co-founder, Seale happened to be in New Haven for a speech at Yale during the second day of Rackley’s confinement. And after turning over state’s evidence and confessing to the murder, Panther George Sams Jr. claimed Seale learned about Rackley’s kidnapping and ordered his murder. The jury was unable to reach a verdict on Seale’s involvement, and the charges were subsequently dropped.

After the trial, Seale ran for Mayor of Oakland in 1973, and earned the second most amount of votes in a field of nine. But he lost the subsequent runoff. He left the Black Panther Party in 1974, according to some accounts due to a physical altercation with Lewis due to Lewis’ desire to produce a movie on the Panthers. Lewis and his bodyguards allegedly beat Seale with a bullwhip, though Seale denies these events occurred. Despite their parting of ways, their demand for equality as laid out in their Ten Point Platform—which includes demands for full Black employment, an end to police brutality, the end of “robbery by the capitalists” of the Black Community, and decent housing—remains a touchstone for those calling for social justice.

In 1987 Seale published his autobiography A Lonely Rage, as well as cookbook Barbeque’n with Bobby Seale: Hickory and Mesquite Recipes. He’s since taught Black Studies courses at Temple University and has toured the country to speak to college campuses about his experiences as a Black Panther and to encourage community organizing. He still lives in Oakland.

Julius Hoffman

Frank Langella’s horrifying depiction of a biased and borderline senile jurist does not appear to be far off the mark from the real Judge Julius Hoffman, a figure very much unprepared for the 1960s or the major trial placed in his lap. Literally born in the 19th century—1895 to be exact—Hoffman was a Northwestern graduate and private lawyer before becoming a Judge of the Superior Court of Cook County in 1947. President Dwight Eisenhower then nominated him to the bench of the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Illinois in 1953.

Apparently already having developed a reputation for bias and incivility before the movie’s famed case, The Trial of the Chicago 7 is correct in noting that a 1974 survey of Chicago attorneys found that 78 percent of them had an unfavorable opinion of Hoffman’s court. However, the judge never actually lost the gavel or suffered severe consequences. Although when the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Seventh District first struck down his numerous contempt convictions and then the subsequent convictions of the Chicago Seven causing a riot, they did so in part because Hoffman exhibited a “deprecatory and often antagonistic attitude toward the defense.”

In 1972 Hoffman assumed senior status, which acts as a semi-retirement for federal judges where they receive a full salary but have the option to take on a reduced caseload, allowing the U.S. president to select a new jurist for their bench. However, Hoffman continued to oversee cases throughout the ‘70s—hence his notorious bad marks in Joseph Goulden’s survey—and continued to judge cases until the 1980s.

In 1982 the Executive Committee of the United States ordered Hoffman not be assigned any new cases after further complaints of erratic behavior and abuse of power. He still was allowed to preside over his ongoing cases, however, until his death a year later. He was a week away from turning 88.

William Kunstler

Both before and after the Trial of the Chicago Seven, William Kunstler was famous for finding himself at the center of the most politically controversial cases that always ended up on the front page. A “radical” lawyer who received his law degree from Columbia after attending Yale as an undergraduate—with a stint in the U.S. Army during World War II in between—Kunstler was already an ACLU director in 1964, five years before the movie’s trial. He’d become an ACLU board member by 1972.

Before the film’s trial he represented Freedom Riders in 1961 Mississippi and at various times advised the likes of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Stokely Carmichael, Lenny Bruce, and the Catonsville Nine (Catholic activists who burned Vietnam War draft files in Maryland). He also less glamorously defended Jack Ruby.

After the movie’s trial, Kunstler worked with the American Indian Movement (AIM), defending Russell Means and Dennis Banks, two leaders of AIM who helped lead the 1973 occupation of Wounded Knee, and defended AIM members again after the murder of two FBI agents. He also defended John Hill who was charged (and eventually convicted) of killing a prison guard during the Attica Prison riot of 1971. Yet his defense helped convince New York Governor Hugh Carey to pardon Hill…. He also defended clients tied to the mafia, including Joe Bananno, John Gotti, and Louis Ferrante.

At the time of his death in 1995, due to heart failure, Kunstler was defending Omar Abdel-Rahman, aka “The Blind Sheik,” for the 1993 World Trade Center bombing. Abel-Rahman was later convicted.

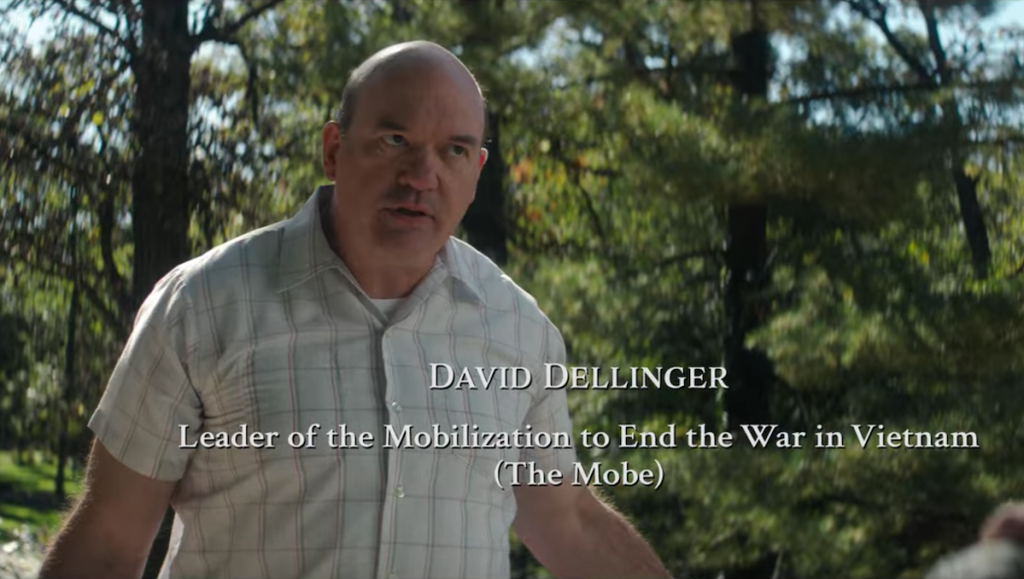

David Dellinger

Prior to being one of the Chicago Seven, David Dellinger was most famous for his radical pacifism during World War II. During the 1930s he’d studied at Yale and Oxford, even touring Nazi Germany in 1937 before the war. He then worked as an ambulance driver in the Spanish Civil War and came to the conclusion he would remain totally anti-war as a result. He was arrested in 1943 after failing to report for his draft physical, and was ultimately imprisoned despite his conscientious objections. In prison he helped protest racial segregation of federal dining halls, leading to their integration.

Throughout the 1950s and ‘60s, Dellinger participated in freedom marches in the American South, protesting segregation. He became acquainted with Dr. Martin Luther King in this time. He also traveled to both South and North Vietnam in 1966, having contact with North Vietnam President Ho Chi Minh.

After the war he stayed politically active, including when he staged a sit-in at Chicago’s Federal Building during the Democratic National Convention of 1996. He also protested free trade in 2001. He received the Peace Abbey Courage of Conscience award in 1992. He died in 2004 at the age of 88.