George Lucas’ Original Indiana Jones 4 Story Was Even Worse Than Crystal Skull

Before Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull, George Lucas tried to make a full-on alien invasion Indy flick in the 1990s, and it’s even crazier than it sounds…

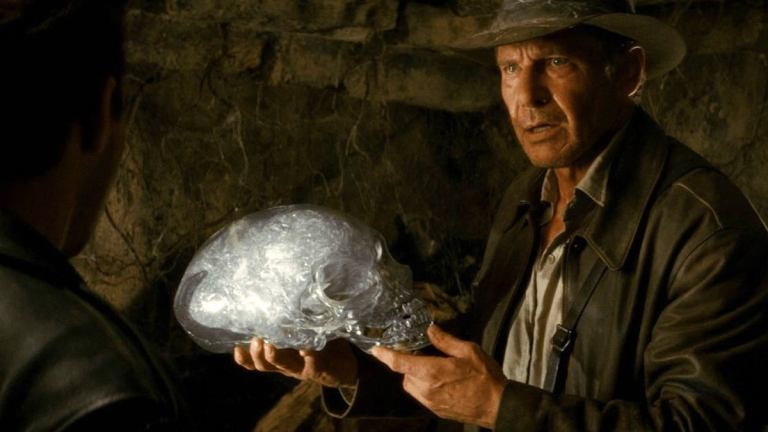

Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull does not have a good reputation. Released in 2008 and almost a full 20 years after what was considered the ending of a trilogy, the fourth Indiana Jones picture was directed by a different kind of Steven Spielberg, one who’d been primarily focused on adult historical dramas since the turn of the century, and starred a much older Harrison Ford. It felt different too, even as it tried to act largely the same as the film that came before it, Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade (1989). This internal refusal to admit Indy had changed was only compounded by the dubious choice to tie aliens to the film’s central mystery—much to the chagrin of the film’s star.

While the movie received some positive notices from critics during release, including Roger Ebert, fans were instantly divided on the film’s overly sentimental tone, its use of modern CGI special effects, and especially the fact that the titular crystal skull turned out to belong to a little gray man who at the end of the film goes home by way of a flying saucer. Even 15 years later, and on the eve of Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny’s release, the man who took the reins of the franchise over from Spielberg, director James Mangold, told Den of Geek magazine, “One of the things I thought about a lot was why the last Indiana Jones movie struggled.” (For the record, he suggested it was due to more than just aliens.)

Nonetheless, and despite the many other valid critiques folks have with Kingdom of the Crystal Skull, after reading where producer George Lucas wanted to take the franchise in the 1990s… it could have been worse. But then it’s hard to think otherwise after just reading the title Lucas originally had in mind for the fourth Indy movie: Indiana Jones and the Saucer Men from Mars.

As that heading suggests, there once was an intention by Lucas, as well the screenwriter he tasked with the project, Jeb Stuart, to turn Indiana Jones into a 1990s sci-fi spectacular that could’ve been comparable to Independence Day (1996), particularly if Saucer Men from Mars had gone into production before Roland Emmerich’s famous alien invasion flick was released. And it would’ve featured callbacks not just to 1981’s Raiders of the Lost Ark—which still occurred in Crystal Skull by way of Marion’s return—but also Temple of Doom (1984) and The Last Crusade. And judging by this version of the script, it was on track to be an absolute train wreck.

Aliens, It Had to Be Aliens

The draft of Indiana Jones and the Saucer Men from Mars examined for this piece was at least a second attempt by Stuart to synthesize his and Lucas’ ideas about what the Indiana Jones movies could become into a narrative. Dated Feb. 20, 1995, this “revised draft” was turned in well after Stuart was first brought aboard by Lucas in late 1993, back when the maestro of yesteryear genres and baby boomer nostalgia first got an itch to do Indy IV.

When Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade released four years prior to that, it was generally recognized to be the end of the road, complete with Ford’s Indy, his father Dr. Henry Jones Sr. (Sean Connery), and their friends riding off into the sunset (and in a classic John Ford shot, which is now even more obvious after the ending of Spielberg’s The Fabelmans). Spielberg considered that chapter of his life closed, especially as he began tackling sober-eyed stories of real-life horror with increasing frequency in the ‘90s, beginning with the Oscar-winning Schindler’s List (1993).

Lucas, on the other hand, produced the fairly underrated The Young Indiana Jones Chronicles on television from 1992 to 1993, including a fan-favorite episode in ’93 where Ford cameoed as a middle-aged Indy, appearing in a wrap-around story where Dr. Jones takes a breather and reminisces about how he learned to play the saxophone while waiting tables at a jazz club in ‘20s Chicago.

It was while watching Ford handle a horn with gray hair that Lucas began imagining an Indiana Jones film where Indy was a little older and more seasoned. It could also be a movie where instead of punching Nazis, he would punch both Soviet commies and the paranoid Americans who saw Red shadows everywhere, especially academia. This would be how Lucas transitioned Indiana Jones from the type of 1930s and ‘40s B-serials that inspired Raiders of the Lost Ark to their 1950s successors; an era that was obsessed with alien visitors and atomic weapons.

In other words, from the outset, Lucas wanted Indy to stare down flying saucers and narrowly survive a nuclear blast.

Tapping Stuart for this project also made sense, as he helped at least lay the foundation for two of the best action movies of the previous five years: Die Hard (1988) and The Fugitive (1993). Both films featured other screenwriters too, however Stuart showed a knack for developing strong movie-star-ready scenarios that let leading men shine while also stringing together set pieces in a way that was propulsive and did not seem to dumb its characters down. Those qualities are visible in Indiana Jones and the Saucer Men from Mars’ extended prologue.

Beginning on crocodile-infested waters in the deep jungles of Borneo, Stuart’s opening plays like the greatest hits from Raiders of the Lost Ark. Indy and a “native” sidekick are besieged by pirates in their rival steamboat. Those pirates, in turn, work for an evil French archeologist who wants the maps and golden idol Indy has already found.

The nostalgic familiarity here is used as a backdrop for the opening’s real purpose: to create a ‘90s blockbuster meet-cute where Indy is introduced to the principal love interest of the film, Dr. Elaine McGregor. She is one of the greatest linguists in the world, fluent in 49 languages; she also suffers from that bland ‘90s action movie depiction of female professionals where she’s described as “beautiful” and doesn’t act like other girls. Still, her only qualities appear to be her beauty and willingness to get her hands dirty in the field with the guys.

With the film being set in 1949, Ford’s Indy is older, a WWII vet, and is looking to settle down. Hence by the end of the prologue (which features a six-week time jump) he is proposing marriage to Elaine, albeit beginning with a clever beat where they’re introduced in extreme close-up, apparently in a moment of romantic intimacy, before the camera spins upside down and reveals they’re hanging by ropes over a pit of man-eating ants.

As with all other Indiana Jones movies, this is just the end of his most recent adventure and a prelude to the next, which begins with a rather hackneyed sequence wherein Elaine stands Indy up on their wedding day. All the old favorites are in attendance to the ceremony too: Sallah (John Rhys-Davies), Short Round (Ke Huy Quan), and even Marion (Karen Allen) and Willie (Kate Capshaw), the latter of whom Sallah admonishes for still being hung up on Indy. (One particularly bad scene involves the pair of exes taking Indy out for drinks after Elaine leaves him at the altar.) Yet this sequence largely seems to exist to give Sean Connery something to do as he returns as Indy’s best man and has lengthy scenes where he still nags his adult son.

Connery’s return would’ve also given us the best line in the movie: After Elaine breaks the hearts of both Indiana and her own parents, Henry Sr. puts his arm around Elaine’s father and says, “Are you a golfing man, Fred? I’ve always found that in extreme cases like this, it’s best to go play a round of golf.”

In theory these sequences are also meant to establish Indy has changed into an older man looking to settle down. But in practice, Elaine is so underdeveloped beyond being efficient at transcribing ancient and (later) alien languages that the fact she stands him up never registers. It’s bland 1990s blockbuster plotting, not unlike the “love story” in Spielberg’s The Lost World: Jurassic Park (1997). The most important part of her disappearance is that it starts the actual mystery. What exactly did pull Elaine away from the wedding? (Spoiler: Aliens).

Communist Paranoia Is the Main Focus

As it turns out, Elaine was called away by a snooty type named Bob Bollander. Bollander works for the OSS (the U.S. intelligence service during World War II and before the formation of the CIA). Along with the even more archetypal General McIntyre, he feels compelled to recruit Elaine straight from her wedding ceremony because something unimaginable has happened—a flying saucer was struck by lightning and crash-landed in New Mexico.

That’s right, Indiana Jones 4 was originally intended to pivot entirely around the conspiracy theories associated with the alleged alien coverup in Roswell, New Mexico. And yet, while charred, seven-foot tall alien corpses and ancient extraterrestrial artifacts are far more foregrounded in Saucer Men from Mars than Kingdom of the Crystal Skull, this draft of the script seems most preoccupied with delving into the Cold War paranoia of its setting. That was also a feature in the final film released in 2008, but those elements turn out to be just remnants left over from Lucas’ original vision in the ‘90s.

Most of the action sequences before the third act in Stuart’s script revolve around Soviet spies who have infiltrated the military base built overnight around the alien crash site, with one of the operatives being a former friend of Dr. Jones from their WWII days. This main rival is rather unimpressively described as “Russian James Bond” on the page (presumably most of the characterization would’ve come down to casting). At various points, the Russians kidnap Elaine, steal an alien artifact, and even kidnap Dr. Jones when he intervenes.

They also facilitate an infamous sequence that survived all the way to Kingdom of the Crystal Skull: Indiana Jones, a nuclear explosion, and the aid of a remarkably well-made refrigerator. Yep, the “nuke the fridge” sequence was originally in Saucer Men from Mars, although it was (maybe?) a little less fantastical. At least in this version, Indy pushes the fridge into a crawl space beneath a house’s floorboards and locks himself inside the appliance right before the atom bomb goes off, thereby surviving the blast without also being miraculously knocked a dozen miles out of harm’s way.

Even so, Indy relying on a thin layer of lead to survive an atomic fireball, and then somehow not being exposed to catastrophic amounts of radiation while waiting for the clean-up team to find him, leaves a lot to be desired.

So does much else of the film. If alien invasion movies like The War of the Worlds (1953) and Invaders from Mars (1953) were Lucas’ touchstones for this script, then at best Indy is a more proactive version of the scientist or professor character in those movies who is always pontificating in the background with exposition disguised as on-the-fly theorizing. For most of the second act of the movie, Indy becomes a strangely passive character while bickering with U.S. Army stereotypes who tell Indy “the atom is our friend.” Eventually, they turn on him too as they become suspicious of Dr. Jones’ friendliness with Russian agents during the war. Indy strangely remains inert though, fading into the ensemble of a bland invasion movie instead of being the plucky hero always on the move.

As a consequence, only the heavily derivative prologue feels like a proper Indiana Jones movie, with the rest of the action being stuck in the exotic location of… small town, USA circa 1949. The way Lucas envisioned the series was that Indy could have adventures in different types of genres as opposed to just adventure flicks (his original idea for Indy III was to make it a haunted house movie before Spielberg insisted on introducing us to Junior’s stern father). But by putting Indy into a 1950s alien invasion film, Lucas robs the character of his sense of danger.

And the alien movie he’s in isn’t that great either…

Countdown to Invasion

Perhaps the most interesting thing about the extraterrestrial backdrop of Indiana Jones and the Saucer Men from Mars is how much it seems to draw on Spielberg’s own Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977) while simultaneously predicting Independence Day and Signs (2002). In fact, the story still seemed several drafts away from fully locking down its MacGuffin, which in this script was a stone cylinder found on the crashed flying saucer. It includes coded ancient languages carved onto each side: Egyptian hieroglyphs, Mayan markings, and Chinese pictographs, among others.

The implication is that the aliens have been visiting us for a long time and likely helped build ancient civilizations. Yet this Chariots of the Gods setup is largely underdeveloped and ignored (as opposed to becoming the central mystery of Crystal Skull). What the stone cylinder says about the movie’s plot, instead of ancient civilizations, is much more important to Stuart’s script, even if the mechanics were still a muddle. Ultimately, Dr. Jones and Dr. McGregor deduce that it must represent instructions for how to fuel the flying saucers. Further if those directions are ignored, the device will start to glow with increasing intensity.

Near the start of the third act, Indy ominously states to General McIntyre what surely would’ve been the line of the trailer: “She was right… the numbers represent a descending scale… a countdown.”

This line is almost verbatim what Goldblum tells the President of the United States about the alien code he discovered in our satellites in Independence Day: “In approximately six hours, the signal is going to disappear and the countdown is going to be over… Checkmate.”

We do not actually see exactly what checkmate would’ve looked like in Saucer Men from Mars, however Indy and Elaine tenuously reason that the stone cylinder must be returned to a nearby mountaintop. Otherwise “dragon fire” will fall. As the countdown descends into the third act, we get a glimpse of that too, beginning with a flying saucer that crashes the Soviet plane that attempts to take Indy and Elaine to Moscow, and then outmaneuvers two rudimentary U.S. jets, including by melting one of them with a heat ray.

After crash landing in a small town, Indy and Elaine are also pursued by aliens on foot in a sequence that mirrors Close Encounters and Signs. Later on, they’re abducted from a ‘50s drive-in where, while hiding, the two almost-newlyweds are so distracted by making out in the backseat that they’re oblivious to the fact their convertible has been captured by a tractor beam and is flying in the sky! Even with all this ‘90s action movie spectacle, the actual aliens of the film still feel poorly constructed and like a work-in-progress. They melt American planes and during the climax completely obliterate McIntyre’s army in a massive special effects sequence involving explosions and whirling sand tornados.

Yet Indy and Elaine are also defensive of the visitors in what appears to be a theme about trusting foreigners. This feels undercooked in a movie where both the Soviets and extraterrestrials have killed servicemen and at various points try to kill the two leads. The stakes are never defined, and the aliens ultimately become little more than UFO straw men used to facilitate various set pieces, including a mountaintop climax that plays like a more violent (and boring) version of the end of Close Encounters, including when Bollander out of nowhere believes he can harness the alien cylinder to his advantage and shouts, “Bow down rulers of the universe, for I now have the power!” Flying saucers promptly incinerate him.

The screenplay feels decidedly unfinished, with only the ending seemingly ironed out: Indy and Elaine get a second walk down the aisle where Henry, Marion, Willie, and Sallah all look on in approval. In the final beat, their “Just Married” car is driven by an adult Short Round who asks, “Where to, Dr. Jones?” Indy looks up from kissing his bride, “The airport, Shorty, and step on it.”

The Road Not Taken

Upon reading the Indiana Jones and the Saucer Men from Mars script, it’s obvious that the film was not ready to be shot—and it never would be. We’ve only heard glimpses of what occurred behind the scenes during the development of the project, but unsurprisingly, reports suggest Spielberg was reluctant to do another alien movie after Close Encounters and E.T. (1982), although in 2005 he tried his hand at a far less tongue-in-cheek alien invasion film when he remade War of the Worlds as a post-9/11 parable. Meanwhile in 2008, Lucas admitted to Entertainment Weekly that Ford rejected the treatment.

“Harrison said, ‘No way am I going to be in a Steven Spielberg movie like that,’” Lucas recalled. “And Steven said, ‘I don’t know, I don’t know, I don’t know.’”

According to Laurent Bouzereau and J.W. Rinzler’s The Complete Making of Indiana Jones, Jeffrey Boam (the screenwriter of The Last Crusade) continued to rework Lucas and Stuart’s ideas well into 1996, but after the release of Independence Day, Spielberg had enough. Seeing the similarities in the stories, he told Lucas he would not be making an alien invasion movie.

So Saucer Men from Mars was abandoned, and the fourth Indiana Jones movie transformed into something else, likely finding its best form in a script by Frank Darabont (The Shawshank Redemption, The Green Mile). Spielberg and Ford liked Darabont’s treatment, which was also the first to realize they should bring back Allen’s Marion for more than a cameo. However, Lucas vetoed it.

Lest you worry that it might’ve been the perfect lost movie, Darabont’s Indiana Jones and the City of the Gods largely reads like a smarter, better written, and edgier version of Kingdom of the Crystal Skull, complete with waterfall gags and an alien MacGuffin. Eventually, David Koepp (War of the Worlds, The Lost World: Jurassic Park) penned a version that all parties could agree on—and they made it.

Lucas still sometimes hints to the press that he thinks Indiana Jones could be more than the same formula time and again. In 2008, he told Total Film Indy should traverse different genres, and he lamented to Vanity Fair, “We’re sticking with having it look pretty much the way the other ones did. Steven decided, and that was out of my control. I mean, I had a lot of say about the ‘50s [setting]. Ultimately, he wanted it to feel like the other movies, and it does.”

To Lucas’ credit, Indiana Jones had the opportunity to be more than the plot of Raiders done roughly four times over. While Temple of Doom is certainly the weakest and most uneven of the original trilogy, it deserves praise for attempting a completely different story wherein Indy is essentially lost in an imperialist fantasy version of India, complete with human sacrifices and hidden cults as the main villains. It’s a story of desperate escape, not a race to the MacGuffin.

However, even in that film, Indy is combatting the Thuggee, a historic gang that existed in India until the 19th century, albeit modern Indian scholarship now asserts their murder of travelers on the road was either exaggerated or invented by British powers to justify colonialism. Either way, that sordid adventure is rooted in actual legends and stories, whether true or not (see also: the Ark of the Covenant’s supposed origins on Mount Sinai).

Turning Indiana Jones into just another sci-fi franchise where CGI flying saucers would blow up military planes and tanks is honestly… kind of dull in comparison. It robs the character of his mystique, and in the case of early drafts of Saucer Men from Mars, they didn’t even land on a particularly good alien invasion story in which to insert Dr. Jones. At least by going the Chariots of the Gods route, where an early civilization’s achievements were the results of visitors from the sky, Kingdom of the Crystal Skull looks better in contrast.

Still, we hope there are no aliens in Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny.