Oppenheimer: 11 More Movies to Watch About the Bomb and the Cold War

Want to feel even worse about our headlong rush to self-destruction? Then watch these movies as an Oppenheimer chaser.

Films about the end of the world are nothing new. But films about the real end of the world–the moments in human history that seem to have put us on an inevitable path toward our own self-destruction–are less frequent. In the 1950s, as the Cold War took hold and the threat of nuclear war escalated, most of the films that came out dealt with it in terms of metaphor, usually sci-fi ones, like giant irradiated lizards and insects standing in for hydrogen bombs.

Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer addresses one of those moments in history head-on, giving us not just a glimpse into the tormented mind of the “father of the atomic bomb,” but a you-are-there, immersive front row seat to the very moment in which the first bomb was detonated and the end of the human race came into clear view, starting with what many now consider to be the morally monstrous decision to drop two of the things on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

But while such films are far less available than the monster mashes we mentioned above or Mad Max-style post-apocalyptic survival sagas, there are some that–in dramatic, comedic, surreal, or pseudo-documentary fashion–tackle the origins, aftermath, and repercussions of the A-bomb in terms that make the horror of it stand out just as sharply. If Oppenheimer left you wanting more, here are 11 more films to watch.

The Beginning or the End (1947)

Like another film later in this list, this movie is now fairly obscure. In fact, we initially confused it with Beginning of the End, an atom age sci-fi schlockfest about giant irradiated locusts. But this stands as the first Hollywood effort to chronicle the development of the atomic bomb. Coming just two years after the completion of the Manhattan Project and the attacks on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, it had the arguable benefit of General Leslie Groves (the real-life military head of the project, played by Matt Damon in Nolan’s movie) aboard as a consultant (he’s played in the film by Brian Donlevy, who would later go on to sci-fi fame as the star of the first two Quatermass movies).

A number of the real scientists refused to allow themselves to be portrayed in the film (which they could do back then), although Oppenheimer himself gave his approval. Still, the loose mixing of fiction and fact, the creation of composite or new characters, and the lack of scientific accuracy (many of the details of the bomb’s development were still classified at the time) make The Beginning or the End seem closer to after-the-fact propaganda than a genuine look at the events it portrays.

Hiroshima (1953)

By the early 1950s, Japanese cinema was finally able to produce films about the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The Japanese Teachers Union, a powerful labor union that was trying to make up for indoctrinating students into Japanese imperialistic propaganda, funded two films that approached the subject in wildly different fashion. 1952’s Children of Hiroshima was done in a maudlin, melodramatic, and apolitical style that left the JTU disappointed, so the following year they commissioned Hiroshima.

Hiroshima can’t be mistaken for a tearjerker. Using thousands of survivors of the real bombing as extras during the film’s brutal recreation of that horrible day (the film’s lead actress, Yumeji Tsukioka, was also a native of the city), the film does not spare the viewer from an up-close view of the blast and its aftermath, both physical and emotional. The film calls out both the Japanese imperial government and the U.S. military for bringing the bomb down on Hiroshima, and its U.S. release in 1955 gave American citizens their first opportunity to actually see images of the blasted city.

Incidentally, the film’s composer, Akira Ifukube, went on to create the score for the classic Gojira, Japan’s attempt to address the bombings through the use of a radioactive monster as metaphor.

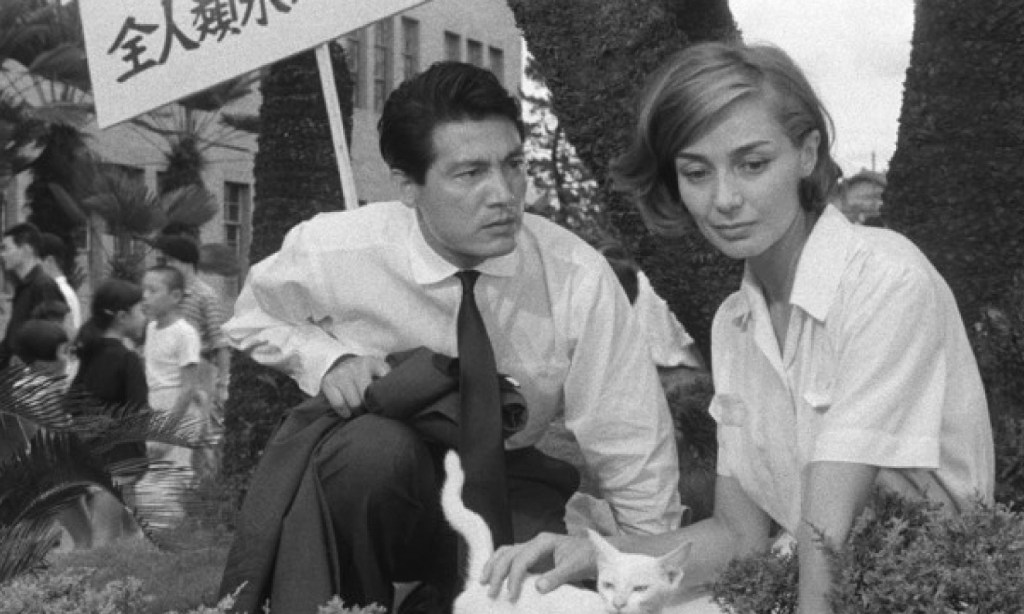

Hiroshima mon amour (1959)

One of the key early titles of the French New Wave and the feature debut from French director Alain Resnais, Hiroshima mon amour’s place in cinema history would be secure even if it wasn’t a timeless, sensual story of romance in the aftermath of war. A Japanese architect (Eiji Okada) and a French actress (Emmanuelle Riva) embark on an affair while recounting their memories of war–in his case, losing his family in the A-bomb attack; in her case, losing her German lover and becoming an outcast.

While Nolan’s film and this both tackle the subject of the atomic bomb from completely different viewpoints, they do share a predilection for using flashbacks and non-linear narratives (something Nolan has utilized since the start of his career). The first hour of Oppenheimer, in particular–with its dreamlike visions and jumps in time–may in some ways be a tribute by Nolan to Resnais’ groundbreaking film.

On the Beach (1959)

Stately, somewhat maudlin, yet profoundly somber and ultimately devastating, Stanley Kramer’s adaptation of Nevil Shute’s novel focuses on the inhabitants of Melbourne, Australia, the last people yet to be affected by a global nuclear war. Yet their days are numbered, as a poisonous radioactive cloud creeps inexorably toward the continent to wipe out the last vestiges of humanity. Everyone begins to prepare for the end in their own way, some of which is deeply shocking.

The presence of major stars like Gregory Peck, Ava Gardner, and Fred Astaire, at first seemingly reassuring, only drives the horror home as we realize that no one will escape the movie alive. And the final scenes of empty, windswept streets, devoid of all life, are in their way as brutal as any more visceral portrayal of the aftermath of nuclear war. Haunting and unforgettable.

Dr. Strangelove, or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1964)

As the story goes, director Stanley Kubrick was working on a serious script about an accidental launch of nuclear missiles but kept discarding things that, from his research, just seemed too absurd to use in a sober-minded thriller. That’s when the idea hit him to completely change his approach and write the film as what he called a “nightmare comedy.”

The result is one of the greatest films of all time, a hilarious–yes, hilarious–look at how the buffoonery, egotism, and megalomania inherent in human beings, especially those entrusted with protecting civilization, can lead quite easily to the end of the world. With a cast led by Peter Sellers (brilliant as the president, a British soldier, and the titular Nazi refugee scientist now working for the U.S.) and George C. Scott, Dr. Strangelove skewers our control over the levers of power and is just as terrifying as any straight drama or documentary about the same subject.

Fail Safe (1964)

While Kubrick’s Dr. Strangelove was based on a 1958 novel called Red Alert (from which Kubrick kept the basic plot but turned it into a black comedy), another film with a very similar premise, based on a 1962 novel called Fail-Safe, went into production at virtually the same time. In fact, Kubrick tried to legally block Fail Safe from going into production, accusing the authors of that book of plagiarizing Red Alert. The lawsuit was eventually settled, with Fail-Safe coming out eight months after Dr. Strangelove.

As a result, Fail Safe did not fare well at the box office and was sort of dismissed in the wake of Kubrick’s classic. But as a thriller on its own terms, and a serious mirror image of the Kubrick film, Fail Safe holds up remarkably well. Directed by Sidney Lumet and starring Henry Fonda, Walter Matthau, Fritz Weaver, and others, it’s an extremely tense, gripping drama in which the President (Fonda) must make an unspeakable choice to prevent nuclear catastrophe.

The War Game (1966)

Originally commissioned by the BBC just two years after the Cuban Missile Crisis brought the world to the brink, this faux-documentary from director/provocateur Peter Watkins proved so horrifying that the network pulled it before it was even broadcast, instead letting it have limited theatrical and festival screenings. It did eventually premiere on British airwaves–nearly 20 years after it was first supposed to–around the same time that similar films like Threads and The Day After also came to the fore.

The film plays as a combination of news report and found footage, showing England’s preparations for nuclear war, the catastrophic event itself, and its aftermath, in which what’s left of the country’s infrastructure and social services quickly collapse into anarchy and barbarism. Working with limited resources, Watkins nevertheless creates a string of nightmarish images and sequences, culminating in a group of orphaned children answering “nothing” when asked what they want to be when they grow up.

Black Rain (1989)

Not to be confused with Ridley Scott’s crime thriller from the same year, this Japanese film focuses on the long-lasting and horrific aftereffects of the Hiroshima bombing on the members of one family and many others who survived the blast. The main character Yasuko (Yoshiko Tanaka) is a young woman who cannot find a suitable husband because all the nearby families are concerned that she will grow ill or not be able to bear healthy children as a result of being in Hiroshima on the day of the attack. In a terrible irony, it’s when she finally falls in love that she begins to get sick.

Of course her fate is sealed no matter what, just like those of many others around her and her family. Black Rain sensitively explores both the immediate, nightmarish impact of the bomb and the suffering it created for years afterward, painting a mournful, intimate portrait of the human devastation wrought by the terrible weapons unleashed upon innocent souls.

Fat Man and Little Boy (1989)

Before Oppenheimer, another of the few more or less mainstream theatrical motion pictures to feature the physicist and focus on the Manhattan Project was this drama from director Roland Joffé (The Killing Fields). Paul Newman headlines the movie as General Leslie Groves, while Dwight Schultz, perhaps best known around these parts as Lt. Reginald Barclay on various Star Trek series, portrayed Oppenheimer.

The movie essentially chronicles the same material as the middle section of Oppenheimer, including Groves’ recruitment of the scientist to lead the project, the various challenges they faced, some personnel clashes, and a few fictionalized incidents–including the death of one young scientist, played by John Cusack, after he’s exposed to radiation (two researchers actually died in similar circumstances, but after the Manhattan Project was completed). The film ends with the successful testing of the bomb in New Mexico. Not a success at the box office or with critics, it’s now a largely forgotten curio.

Thirteen Days (2000)

The nightmare that haunted Oppenheimer for the rest of his life after the creation of the A-bomb–full-scale global devastation wrought by the use of atomic weapons–almost arrived in October 1962 when a 13-day standoff between the U.S. and the Soviet Union over the placement of Soviet missiles in Cuba took us to the brink of all-out nuclear war. Roger Donaldson’s Thirteen Days dramatizes the Cuban Missile Crisis quite effectively, drawing on (at the time) newly declassified material to paint a gripping picture of the Kennedy administration’s frantic, thankfully successful efforts to avert Armageddon.

The film has been taken to task for elevating the importance of Kevin Costner’s presidential adviser, Kenneth O’Donnell, in the crisis, but in the end that doesn’t take away from the movie’s mostly straightforward recreation of what might have been the most terrifying two weeks in human history. The always underrated Bruce Greenwood is also low-key spectacular as President John F. Kennedy. Sort of like Oppenheimer, Thirteen Days shows us incredibly smart, yet still very flawed human beings grappling with questions almost beyond comprehension.

Good Night, and Good Luck (2005)

The Red Scare and McCarthyism rear their ugly, vicious, anti-American heads in Oppenheimer, as elements in the U.S. government uses the physicist’s liberal leanings and past associations with American communists to take him down after he speaks out strongly against the development of thermonuclear weapons. So if you’ve gotten your fill of the nuclear-themed movies on this list, one of the more incisive looks at another dark chapter in American history may be just the thing to cheer you up send you further into despair.

Directed by George Clooney (who also stars alongside David Strathairn, Jeff Daniels, a pre-MCU Robert Downey Jr., and Patricia Clarkson), Good Night recounts the battle of wills between CBS News journalist Edward R. Murrow (a brilliant Strathairn) and the virulent Joe McCarthy (seen only in archival footage), as the former gradually helps turn the tide against the latter’s vile fear-mongering campaign. Good Night is more about the value and responsibility of a free press–more relevant than ever with an insurrectionist trying to return to the White House–but focuses on the same venal politics that ultimately broke Oppenheimer.

Oppenheimer is in theaters now.