Lord of the Rings: How Faithful Are Peter Jackson’s Movies to the Tolkien Books?

As The Rings of Power approaches, we take a look back at how The Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit trilogies approached fidelity to Tolkien lore.

Warning: contains spoilers for The Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit books and movies.

With Amazon’s The Rings of Power series coming out very soon, there’s been a lot of talk about how faithful – or otherwise – the series is to Tolkien’s lore. But what exactly does it mean to be faithful to a book? We all know that no TV or film adaptation can simply take a book and put it on screen. For one thing, everyone imagines something slightly different, and for another, what works in a novel does not necessarily work on screen.

For every BBC 1995 Pride and Prejudice, which as close as any adaptation to taking the words of the book and filming them, there’s a Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets, which ends up feeling slow and awkwardly paced by sticking doggedly to the source material. Even Pride and Prejudice’s most famous scene isn’t actually in the book (where Mr Darcy regrettably doesn’t take any dips in the lake).

Adaptations have to make changes if they’re going to work in a new medium. Having said that, there is a line where ‘making changes’ becomes ‘turning into something completely different’, and some fantasy fiction fans are still smarting a little from the BBC’s Discworld-inspired series The Watch, which was barely recognisable as an interpretation of Terry Pratchett’s characters. It’s a fine line to walk – how well do the Peter Jackson The Lord of the Rings films do?

Left Out: Glorfindel, Tom Bombadil, the Scouring of the Shire

There are some obvious major changes from the books that Tolkien fans have been talking about since the movies came out over 20 years ago. For example, instead of an Elf called Glorfindel, it is Arwen who rescues Frodo from the Black Riders on the way to Rivendell. In another distinct departure, a group of Elves led by Haldir turn up to fight alongside the Rohirrim at the Battle of Helm’s Deep, and Haldir is then killed off.

Both of these are sensible and effective changes. Glorfindel never appears again, whereas Arwen is Aragorn’s love interest, and without Haldir’s death, the only named character lost at Helm’s Deep would be Théoden’s door guard Háma. Nice as Háma is, the audience aren’t too desperately attached to him so Haldir’s death helps to bring some more gravitas to that battle.

Two major incidents from the books were left out all together; the hobbits’ adventures with Tom Bombadil early on, and the ‘Scouring of the Shire’, a chapter right at the end in which the hobbits get home to discover Saruman has taken over and industrialised the Shire.

Again, both of these were sensible changes. Tom Bombadil is so insignificant to the overall plot that has hasn’t made it into any adaptation yet, though since the character is ageless, both he and Glorfindel could turn up in The Rings of Power, which should make their fans happy. And the biggest criticism of the film version of The Return of the King was that it had too many endings, so adding another climactic sequence after the destruction of the Ring would hardly have been a good idea – though it is a shame that Saruman’s alternative death scene ended up tucked away in the Extended Edition.

Added In: Arwen’s Mortality, Faramir’s Temptation

Some material was also added to the films, especially to Arwen’s story. In the books, Arwen sits around looking pretty in Rivendell early on, then disappears for hundreds of pages before turning up to marry Aragorn at his coronation. This does not make for a compelling character and movie audiences would be left wondering why Aragorn chose her over Éowyn. So in addition to replacing Glorfindel, Arwen is given her own storyline in which she is dying and heads off towards the Grey Havens, but changes her mind when she sees a vision of her and Aragorn’s future son. It’s a way of dramatizing her choice to marry the mortal Aragorn, with all the heartache that will cause for an immortal character, and it works well enough and doesn’t change her character arc (such as it is) much from the books.

The most significant added material relates to Faramir in The Two Towers. This really upset book fans as it was the only change that resulted in a key character difference. In the book, after Faramir has found out that Frodo is carrying the One Ring and ruminated on how this is “a chance for Faramir, Captain of Gondor, to show his quality”, he laughs and reassures Frodo and Sam that, having already told them “Not if I found it on the highway would I take it”, he considers that a vow and, unlike his brother Boromir, will protect them and not try to take the Ring. Shortly afterwards he lets them go and sends them on their way.

In the film, Faramir follows up on the temptation to “show his quality” and decides to take the hobbits, with the Ring, to his father Denethor, to try to make his father proud. They get all the way to Osgiliath before an attack by the Black Riders results in Frodo trying to give them the Ring and Sam having to wrestle him to the ground and talk him out of it. Witnessing this, Faramir decides the Ring probably should be destroyed after all and lets them go.

The sequence gives Frodo and Sam more to do, as their major action scene from the book – the fight with Shelob the giant spider-creature – has been moved to third film (because they don’t have any major action scenes in the book of The Return of the King; their journey through Mordor to Mount Doom is covered in only three chapters). But there’s no denying this is the biggest deviation from the source material in the trilogy.

The sequence lets us see how far Frodo is being driven to despair by carrying the Ring, and it gives Sam a really lovely speech about how “there’s some good in this world, Mr Frodo, and it’s worth fighting for”. It does make Faramir a slightly less morally upstanding character than he is in the books, as he gives in to the temptation to take the Ring to his father for quite a while and nearly gets them all killed in the process. But it should be noted that Faramir does, in the end, let the hobbits go just as his book counterpart does, and his struggle is far more dramatic in the movie version, making him a more flawed, and possibly more interesting, character.

Galadriel’s Gifts, Sam’s Front Door, Frodo’s Age, Songs

These are a few of the major talking points, and of course there are smaller changes scattered throughout the films that might be irritating to some book fans. For some, for example, the fact that Galadriel doesn’t give Sam a box of earth from Lothlórien as a gift is annoying. For others, the final image of the movie is a huge irritant, as Sam goes into a hobbit hole with a yellow door instead of the green door of Bag End, which Frodo left to him and his family. There are also many fewer songs than there are in the books, in which the action quite frequently stops for a song about the Olden Days or a sung eulogy for the dead (though quite a few songs and eulogies do appear in the Extended Editions).

Frodo is also thirty years younger than his book counterpart. While this would seem like something that would affect his relationships with the other hobbits, it doesn’t really. Sam is Frodo’s servant and that has a more significant impact on their relationship than their respective ages, while Merry is the most sensible hobbit and Pippin the most foolish, so even though Pippin is no longer the youngest, the character dynamics remain unchanged.

The majority of the movies follow the action of the books pretty closely and much of the dialogue from the books is used. In some places dialogue has been a little bit modernised or moved to slightly different scenes, but much of it is lifted from the novels. Some events are compressed, most notably the time that elapses between Bilbo’s birthday party and Gandalf telling Frodo about the Ring (17 years in the books, a few weeks in the films). But most of the major plot beats are there and the story is clearly the same story, even with the changes.

John Howe and Alan Lee: Illustrating Middle Earth

It helps that Jackson hired the two best known illustrators of Tolkien’s work, John Howe and Alan Lee, to work on the films’ design elements. It’s inevitable that movie characters, sets, and costumes won’t ever quite match whatever a book reader has imagined in their head. But when they look a lot like images readers have been seeing attached to these characters and this story for years, it really helps the films to feel like they are faithful dramatisations of the books.

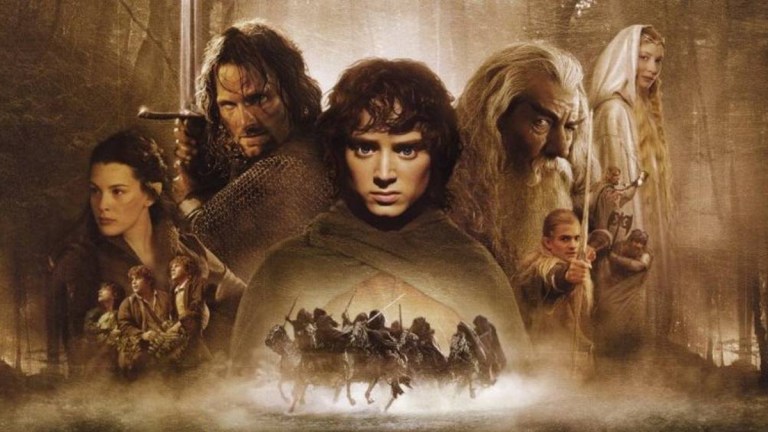

The movies are also generally very faithful to the spirit of the books. We will never forget that first viewing of the first trailer for The Fellowship of the Ring, which showed the entire Fellowship walking over a hill, and in which any book fan could pick out exactly who was who – including which was which among the four hobbits – without needing to know anything about the casting. Most of the movie’s characters feel like they’ve stepped out of the pages of the book, and many of the story’s themes come effectively, like the importance of showing pity and mercy, which saves the world in the end (even if Gollum didn’t entirely deserve it).

What About The Hobbit Films?

We can see just how faithful The Lord of the Rings movies are to the books by comparing them with Jackson’s own film adaptation of The Hobbit a few years later. The Hobbit looks just as good as The Lord of the Rings, and the casting is very good as well. And there’s certainly enough of Tolkien’s story that it’s recognisably an adaptation of it – we’re not in The Watch territory here.

But The Hobbit is not as faithful an adaptation as The Lord of the Rings. It infamously took one short children’s book and used it as the basis for three long, epic movies, as opposed to taking three books aimed mainly at adults and adapting them into three movies (to be fair, Tolkien always considered The Lord of the Rings to be one book, and it was only the publishers who requested it be split into three – but that’s one very long book).

This resulted in a lot of added material. Some of this dramatized scenes only referred to vaguely in the books, which is actually a good idea – movie audiences would have felt quite cheated if Gandalf had gone off to fight ‘the Necromancer’, i.e. Sauron, and they didn’t get to see it. But it meant the film-makers had to invent a lot of the details themselves.

The movies also added lengthy storylines that didn’t appear in the books. It’s fun to see Legolas, who would have been around at that time, but the huge storyline running across the second and third movies in which Kíli has a doomed romance with an Elf called Tauriel, and then Fíli, Kíli, Óin and Bombur get left behind in Laketown for a while, is entirely the creation of the filmmakers.

We can see why they added these plots. There are literally no named female characters in The Hobbit (Galadriel doesn’t appear either) so the movies desperately needed to include some women, somehow, and leaving four Dwarves in Laketown means we have characters we care about besides Bard the Bowman around when Smaug attacks. But it’s undeniable that these come at the expense of remaining faithful to the books.

Ironically, the Hobbit films were sometimes also criticised for being too faithful to the books. Far more songs make it into the theatrical releases of these films than the earlier trilogy, and although they are mostly lifted from the book, they tend feel out of place. This is because the biggest change which makes these films less faithful adaptations overall is the change to the tone. The Hobbit is a mostly light-hearted story (up until the end) about some funny characters having funny adventures. The Hobbit films are not.

The Lord of the Rings started out as a suitable sequel to The Hobbit, and the tone of the early chapters is fairly light, Black Riders notwithstanding. As the story progressed, however, it got darker, more epic-feeling, and more complex, and the lighter tone gradually fell away. This is the other reason Tom Bombadil never makes it into adaptations, besides his uselessness to the plot. The hobbits’ adventures with him, despite the dangers posed by evil trees and ghosts at ancient burial sites, are treated fairly lightly and feel very much like the sort of adventures that befall Bilbo and the Dwarves in The Hobbit.

The Hobbit films tried to take on the epic tone of The Lord of the Rings films, while still adapting most of the action of The Hobbit. This is why, despite all the added material and lengthy running time, some parts (like the group’s meeting with Beorn) were actually cut down, and it’s why some scenes directly taken from the book feel out of place. Dwarves singing a funny song about doing the dishes belong in a fun children’s adventure, but feel like a waste of time in an epic fantasy, and the same goes for goblins singing funny songs. Even Bilbo’s conversations with Smaug, which are great fun and well adapted, don’t quite fit the tone of some of the surrounding scenes.

We already know that The Rings of Power will be creating a lot of new material in the course of its adaptation. There is far less for the writers to go on than The Hobbit had, since they are primarily adapting a timeline from the Appendices to The Lord of the Rings, and we know the timeline of several centuries will be compressed into one human’s lifetime. So in a sense, the series can’t be entirely ‘faithful’ to the plot, as there’s not much plot to be faithful to.

We have high hopes, though, that it will be a faithful adaptation in other ways. The epic tone the series is adopting fits the grand history of the Second Age and the wars and conflicts of Tolkien’s mythology far better than it fitted The Hobbit. Although there are clear differences in the design of the world, with different people working on it behind the scenes, Middle Earth looks enough like the world of the movies to believably portray that world several centuries earlier. Only time will tell whether these younger characters, like Galadriel, Elrond, and even Sauron, feel convincingly like younger versions of the characters we know – but we’re excited to find out.