Looking back at Ronin

Ronin remains much-loved for its car chases - but is there more to it? We salute its 20th anniversary with a fresh spin...

It’s not entirely without good cause that John Frankenheimer’s Ronin is a movie primarily remembered for its elaborate car chases. The movie does after all contain some of the most pulsating, gripping and downright dangerous car chases ever committed to film. There is however much more to this movie than just high-octane stunt work.

With Ronin celebrating its 20 year anniversary in 2018, it’s a decent time to take a look back at an oft-overlooked action thriller that blends tense, high-stake spy-games with an underlying tone of wistful melancholy.

Set predominantly in the French cities of Paris and Nice, Ronin chronicles a multinational band of former secret service personnel and a rogues’ gallery of criminal networks as they seek ownership of a mysterious case. The film’s obscure title is a reference to masterless samurai from feudal Japan who upon losing their employer resorted to becoming nomadic swords-for-hire. Here we witness modern equivalents, highly skilled operatives in a post-Cold War world, now without an agency and seeking gainful employment.

Throughout the movie there’s underlying sense of desolation surrounding these men and the lives they have chosen. This lugubrious mood is aided in no small part by the film’s drab inner-city setting. There is no sheen or polish to the surroundings and no picturesque cityscapes. Instead the film unfolds along tattered streets and under grey skies. It’s a film playing out on rain-splattered cobbles, in dingy side-street bars and dank back rooms in which shifty men in long coats barely talk to one another.

The original screenplay for the movie was written by J.D. Zeik, but a fairly hefty punch-up was then completed by renowned playwright David Mamet. The extent of Mamet’s work on the project is up for some debate however. Zeik’s team remain fairly adamant it was minimal, but the LA Times quoted Frankenheimer himself as saying “the credits should read: ‘Story by J.D. Zeik, screenplay by David Mamet’,….We didn’t shoot a line of Zeik’s script.”

Mamet is widely credited with bulking up the role of Robert De Niro’s enigmatic Sam and his fingerprints certainly appear to be all over a script filled with brisk back-and-forths, cynical retorts and professional lingo. He would eventually be credited on the film but as ‘Richard Weisz’, in a move which stems from his frustrating experience on Wag The Dog after which Mamet swore to only attach his name to films where he receives sole writing credit.

Cinematographer Robert Fraisse also deserves special praise for his work in the movie. The DP made great use of wide-angle lenses in order to achieve the deep focus look that Frankenheimer demanded. The impact of this can be felt in both the quieter interior shots, where the entire crew appear claustrophobically pinned together, and also the busier exterior shots where a full sense of the destruction caused by the city-wide car chases can truly be felt. These chases of course posed their own challenges to Fraisse and his crew, with extensive use of steadicams and a hefty dose of creativity required in order to capture footage at such breakneck speed.

Ronin is also blessed with one hell of an ensemble cast. At its centre of course is Robert De Niro’s former-CIA operative and man of few words, Sam. It may not be his most glamorous or taxing of roles, but De Niro still delivers in spades, giving us an enigmatic character whose impressive array of skills marks him out as a man with an eventful past. Our introduction to Sam is superb, telling us all we need to know about his mindset and cautious nature. Upon arriving at a backstreet cafe, he scans the rundown surroundings. After meticulously surveying the available escape routes, he plants a gun outside the back door before calmly entering through the front. Shortly after entering the cafe, we see him use a trip to the bathroom as an excuse to ensure the back door is unlocked should he require it. When pushed as to why he did this at a later juncture, he delivers the immortal line “Lady, I never walk into a place I don’t know how to walk out of.”

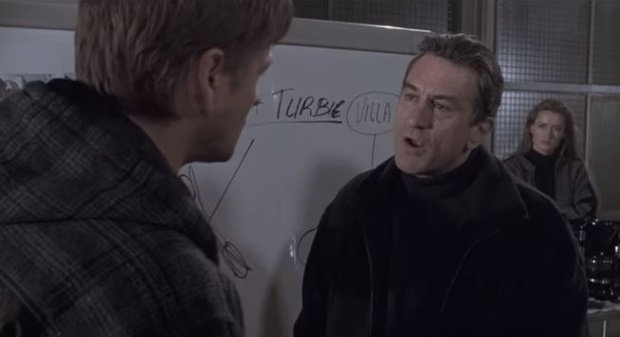

Another standout scene sees De Niro’s Sam delivering a scathing rebuke of Sean Bean’s bewildered former SAS man, Spence. As Spence lays out a woeful heist plan on a whiteboard for the rest of the team, Sam promptly stands up and rubs it out, before emploring his colleague to “draw it again”. While Spence panics and looks befuddled, Sam uses mind games to reveal the beleaguered Brit as a fraud. It’s little moments like this which give us a telling insight into Sam’s battle-tested history.

The characters involved in Ronin are not spies as such, but the film very much possesses that spy-games style aesthetic. It’s a story of skilled operatives working above the law, blending in throughout unknown cities, with only their own wits for protection. There are several wonderful little scenes that deliver a telling insight into the tricks of the trade these men have learned along the way. Scenes such as Sam’s ingenious ruse to capture some photographs of the case, or when he is memorably forced to perform surgery on himself, all add a little bit of extra depth to his backstory.

Alongside De Niro there’s also a strong supporting cast of characters including Jean Reno as local fixer Vincent, Skipp Sudduth (an amateur stunt driver who did most of his own driving) as getaway driver Larry and Stellan Skarsgard as Gregor, the German former KGB man and resident tech expert. Natascha McElhone and Jonathan Pryce meanwhile also do fine work as the determined Irish operatives out to obtain the case at all costs.

Skarsgard is particularly excellent as the double-crossing turncoat, Gregor. He nails the ruthless and unhinged side of the character, with one particular scene near a playground being especially chilling. Sean Bean’s brief turn as poor Spence is also hugely enjoyable, a man clearly out of his depth and pitifully ill-equipped for the fineries of international espionage. My abiding memory of his character being when he excitedly delivers some thoroughly unconvincing cockney rhyming slang about “a bit of raspberry jam back there” after a narrow escape, only to then promptly ask to pull over so he can throw-up.

The actual contents of this much sought after case quite noticeably remain a mystery throughout. As the action unfolds, all we know is that an array of criminal networks are desperate to acquire it for their own nefarious means. At the film’s climax however, we find out that the case and its contents are ultimately of no importance whatsoever. It sits alongside the likes of the Pulp Fiction briefcase and The Maltese Falcon’s Maltese Falcon as one of the great cinematic Macguffins. The case is of vital importance to the terror groups vying for its possession, but for our band of outlaws and operatives, it really is just a means to an end.

As vital as this talented cast and crew all were to shaping the movie, it was undoubtedly director John Frankenheimer who had by far the most prominent impact on the finished article . It’s been said that he was something of an old school director, flexing a great deal of creative control over nearly every aspect of the film’s production, from the extensive stunt work to the precise colour palette.

Frankenheimer is best known for directing 60s classics The Birdman Of Alcatraz and The Manchurian Candidate, as well as for more modest hits including the acclaimed sequel The French Connection 2 and motorsports favourite Grand Prix. It wouldn’t be unfair to suggest however that prior to making Ronin, his star was on the wane somewhat and the film actually marked something of a comeback.

Given his background in political thrillers, fast-paced espionage and the odd motorised action sequence, it’s clear what attracted the director to a project like Ronin. In an interview on the film’s Blu-ray he tellingly notes “I thought I could do it, I thought i could do it rather well. It seemed to fit into things I know how to do.”

How right he was too. Frankenheimer tapped into his extensive experience to create a movie that effortlessly immerses us into its criminal underworld. He captures both the loneliness and the camaraderie of the lifestyle perfectly, as well as the internal dilemma of the men involved who are in theory bound by a strict code, but deep down are forever looking for the highest bidder. The terror networks, the shady operatives, everything feels very sinister, untrustworthy and inherently dangerous. All of which sits neatly alongside the intense bursts of action that the director weaves in.

Frankenheimer ensured that there was a tremendous focus placed on authenticity throughout Ronin’s production. You can clearly tell that the vast majority of scenes were shot on location and you can practically smell the cigarette smoke in the air and feel the drizzle on your face. Where the film’s realism really comes into its own though is during its much lauded car chases. These high-octane sequences are right up there with the likes of Bullitt and French Connection in the discussion of all-time greats. Every second of them was meticulously planned by the director beforehand, who opted to shoot on location on the bustling streets of Nice and Paris. He refused to use CGI to achieve his vision, feeling instead that only genuine stunt work would deliver the authenticity he required.

When it came to the actual task of filming the stunts, De Niro and the rest of the cast would more often than not still actually be in the cars when filming took place. They would be in right-hand drive cars, but sat in the left seat made up to look like they were driving while a skilled stunt driver did the real work next to them. For close-up scenes of the interiors meanwhile, cars would simply be chopped in half and then dragged through the streets by stuntmen in even faster motors.

Its reported that as many as 300 stunt drivers were used for the final chase sequence, and one can only guess at how many BMW’s and Peugeot’s were destroyed in the process. Former F1 driver Jean-Pierre Jarier was just one of the many experts who ripped around the compact city streets at speeds of up to 100 mph.

Frankenheimer and Freisse did superb work in these sequences, immersing us right into the action while still maintaining a sense of the cat-and-mouse pursuit that is unfolding. The shots switch from cramped low-angles in the cars themselves, to wide high angle shots capturing the anarchy following in their wake. The director also noticeably decided against using a score of any kind during the chases, arguing it might distract from the intensity of the moment. His commitment to capturing the chaos is perfectly summed up by a line on the Blu-ray commentary: “I don’t believe that violence happens in slow motion.”

It’s obvious that the director has a great affinity for motor sports and cars in general, with the chase sequences all clearly crafted with great love and adoration. To quote our own Ryan Lambie from his detailed look at the climactic chase, “throughout this scene, Frankenheimer directs with low-key, unfussy brilliance. Robert Fraisse’s gritty cinematography is kinetic and exciting… There’s a real sense here that Frankenheimer and his team are thoroughly enjoying this anarchic blast through Paris. How else can we account for the scene’s sheer length and scale of destruction? “

Ronin is not entirely without faults of course. The love story between Sam and Deidre feels a little out of place and the pace does sag noticeably once the action shifts to the climactic ice-dancing set-piece. However, these minor criticisms aside, it’s still an immaculately crafted and incredibly entertaining action thriller. It’s blessed with a strong cast, a twisting plot and Frankenheimer’s masterful direction which ensured a fittingly desolate and uncompromising tone.

It’s not the flashiest of movies, but that’s part of its stripped back charm. It’s not trying to paint this life as a glamorous globe-trotting romp. Instead it’s a proto-Bourne, showing the grim reality of life on the lam and the guns for hire who operate within it.