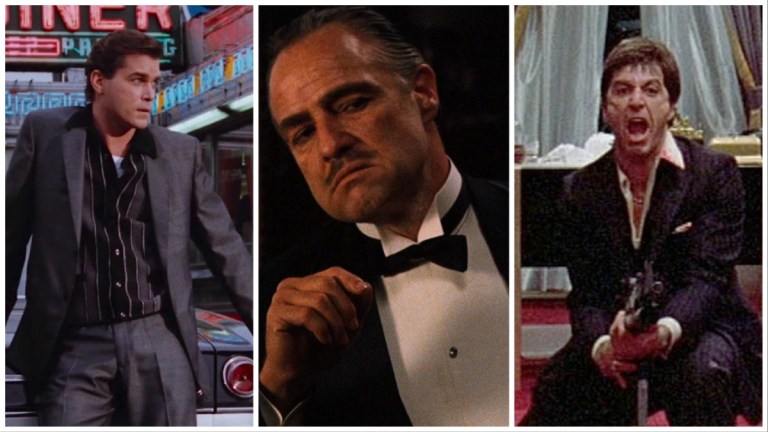

The Best Gangster and Mob Movies Ranked

Organized crime is big business, and cinema has taken it very personal, from Cagney to Coppola.

Gangsters, mobsters, thugs, and mugs. Organized crime holds the upper tier of the international cinematic commission. “Crime pays,” Edward G. Robinson, who played Rico Bandello in the seminal gangster film Little Caesar (1931), is famous for saying. “But only in the movies.” When a good mob movie is on the table, it is an offer no filmmaker can refuse. There is more intrigue, suspense, violence, mayhem, and madness to be found in the criminal element than any other genre.

“Gone are the days of the gangsters,” audiences heard for years, usually in movies about mobsters. They always rise up, even if they are splattered across the ornate fountains of their gangland mansions in the last frame, like Al Pacino’s Tony Montana in Brian DePalma’s Scarface (1983), or rolling down the steps of a church, dead from a hail of bullets. That’s how James Cagney’s Eddie Bartlett went out in The Roaring Twenties (1939). Now, 100 years after that film is set, directors are still aiming their cameras at the public enemies, regardless of what number they come in on Interpol’s watch list.

Here are 15 organized crime films which each made most-wanted lists that budding gangsters need to see.

15. Road to Perdition (2002)

“There are only murderers in this room, Michael.” That’s what Michigan’s Irish mob boss John Rooney (Paul Newman) tells his closest and most loyal enforcer. “There is only one guarantee: None of us will see heaven.” Based on the graphic novel by Max Allan Collins and Richard Piers Rayner, penance in writer-director Sam Mendes’ Road to Perdition unfolds like panels in a comic. Tom Hanks plays Michael Sullivan, Rooney’s top hitman.

As the title suggests this is a road picture, Sullivan and his son Michael Jr. (Tyler Hoechlin) are on the run after his boss’ jealous son Connor (Daniel Craig) kills their family in a mistaken power move. They are not just on their way to Perdition, Michigan, but to a fork which will determine the future of a gangster’s son. Jude Law’s stalking hitman, Harlen Maguire, meanwhile has a second job as a crime scene photographer. He develops the tension which leads to the wholly unexpected shock of an ending.

14. The Long Good Friday (1980)

The first film distributed by George Harrison’s HandMade Films, The Long Good Friday gave Bob Hoskins his breakthrough as cockney mob boss Harold Shand and introduced Helen Mirren as his level-headed posh lover Victoria. Director John Mackenzie packs a lot of energy into a fast-paced and circuitous screenplay by Barrie Keeffe. The audience doesn’t know any more than Harry about the faceless enemy going around bombing and stabbing criminal associates.

Shand kept peace in London for 10 years. His next scheme will make him rich and legit, with help from some illegitimate friends, like the American Mafia. Shand’s plans are disrupted by what he thinks are rival gangsters, but turns out to be much worse: Republican Irish terrorists. “Those boyos don’t play by the rules,” warns a well-connected associate. They also don’t know how to interpret stupid decisions. Let Shand’s face be the last you see. It tells the whole story.

13. On the Waterfront (1954)

On the Waterfront is a gritty portrait of dockworkers under the thumb of gangsters. It is also an allegory for director Elia Kazan’s compliance with Hollywood commie hunters. As great as this film is, in mob circles it’s still the story of a rat. Marlon Brando’s Terry Molloy is a cautionary tale, and not just because he got a one-way ticket to Palookaville. Terry was a boxer who took a dive for Johnny Friendly (Lee J. Cobb) and lost a title shot.

The mobbed-up union president gives the future Godfather actor a no-work job. It’s a lofty position for the conscious-plagued mug who fingered a squealer to the mob. But Terry dances with cops and his brother Charlie (Rod Steiger) pays the price. Friendly has him hung on a hook, and kicks the shit out of the former boxer too. The film should have ended with Terry face down on the dock. It is still a masterpiece.

12. The Departed (2006)

“I don’t want to be a product of my environment,” Jack Nicholson’s Irish mob boss and turnaround informant Frank Costello declares. “I want my environment to be a product of me.” With that he lays out the motivations of the legendary Boston crime head Whitey Bulger, at large and unscathed for years when the film was made.

A remake of the 2002 Hong Kong film Infernal Affairs, Martin Scorsese’s The Departed has everything: Mobsters posing as cops, wannabe cops pretending to be gangsters, secret identities, double lives, multiple twisted endings, a true-life centerpiece, Nicholson, and Leonardo DiCaprio. When it opened, Scorsese said it even had a plot, a personal first for him. Mix Matt Damon’s bad cop-turned-worse, Martin Sheen’s secret meetings, Mark Wahlberg’s South Boston accent, and Alec Baldwin’s every snide comeback into the concrete and it dries into a street crime masterpiece. Scorsese throws surprises from every corner.

11. Miller’s Crossing (1990)

Every scene in the Coen Brothers’ Miller’s Crossing is a kill shot, not for any violence, but because the framing leaves an indelible mark on the brain. The film mixes 1930s gangster films with the film noir atmosphere found in Dashiell Hammett novels. Leo O’Bannon (Albert Finney) is an Irish mob boss. Gabriel Byrne’s Tom Reagan is “the man who walks behind the man, and whispers in his ear.” He whispers so many things we don’t really know whose side Tom is on until the very end of the film, and he still leaves us questioning.

O’Bannon’s rival, mob boss Johnny Caspar (Jon Polito) puts it all in perspective when he asks, “If you can’t trust the fix, what can you trust?” Certainly not John Turturro’s bookie character Bernie Bernbaum. He tests loyalties, and with a gang war in the balance, that’s no quick walk in the woods.

10. Kiss of Death (1947)

Directed by Henry Hathaway, Kiss of Death came so close to a true mob portrayal, real-life gangster Joe Gallo got straightened out and made his button. He would go on to inspire the plot to The Godfather, but what he saw on that screen was sadistic, grinning Tommy Udo, played by Richard Widmark in his debut, Oscar-nominated performance.

Victor Mature stars as Nick Bianco, a small-time hustler who botches a robbery and rats out a heavy name. It turns out to be just what the cops need to bring down the major menace to society. For his troubles, Bianco gets out of jail, free, but told not to pass go or expect protection. With a friendly Udo shadowing, a bad fall is around every corner. Tommy pushes an old woman in a wheelchair down a flight of stairs for dawdling. Tattling? Forget about it.

9. Gomorrah (2008)

The Mafia may have seen a decline since cinema shined a light on it, but their Neapolitan counterpart, the Camorra, continues to thrive. Gomorrah is an adaptation of the exposé by Robert Saviano, who went undercover, working as a waiter at mob weddings. Director Matteo Garrone approaches the film like a documentary, but it feels like those handheld cameras are surveillance tools mounted on the undercover writer. There is no glamor in this telling. This is modern life in Naples and Caserta. Five inter-related incidents show organized crime is found in every level of society. Just as it’s always been.

The arcs are linked by the bagman don Ciro (Gianfelice Imparato), who pays the families of jailed Camorra members. The naturalistic performances leave no room for the tricks of acting. Similarly, there is no flamboyance to the violence, brutal and vicious as it is. There are no morals, or heroics, only victims and wads of cash.

8. New Jack City (1991)

Intended as the Black version of The Godfather, New Jack City introduced an entirely new kind of crime boss. Wesley Snipes’ Nino Brown is as iconic a gangster as any played by James Cagney, Humphrey Bogart, or Robert De Niro. Nino wasn’t just da bomb, he invented it. You can see how the kids on his block all want to grow up to be in Brown’s crew. There is nothing Ice-T can do to make us root for him.

Also starring Chris Rock and Judd Nelson, New Jack City was an anti-drug movie which tried to rob the crack boomers of their glamor. Director Mario Van Peebles, the son of cinematic provocateur Melvin Van Peebles, owes a great debt to Michael Campus’ 1973 crime classic, The Mack, as does Boyz n The Hood, dipping into social alternatives. But the Cash Money Brothers are as classic as the original gangstas.

7. The Roaring Twenties (1939)

Raoul Walsh’s The Roaring Twenties should be seen on a double bill with Francis Ford Coppola’s The Cotton Club (1984). Both are unrelenting romances with gangsters and the jazz age. James Cagney’s Eddie Bartlett comes back from WWI to grim prospects at home. He gets dipped in Prohibition at a speakeasy headlined by Panama Smith (Gladys George), and turns into headline-making bootlegger.

Eddie partners up with his two foxhole buddies, Jeffrey Lynne’s young lawyer Lloyd Hart and Humphrey Bogart’s George Hally. Both could stand some watching. George betrays his boss Nick Brown over spaghetti no less. Lloyd makes a play for Eddie’s sweetheart, Jean Sherman (Priscilla Lane). She epitomizes the era’s sound. When a club snubs her, Eddie buys the joint. Cagney’s rise up the gangster ladder is a tour de force. His stumble down the church steps is iconic. “He used to be a big shot,” some off-key canary says. In crime film history, he still is.

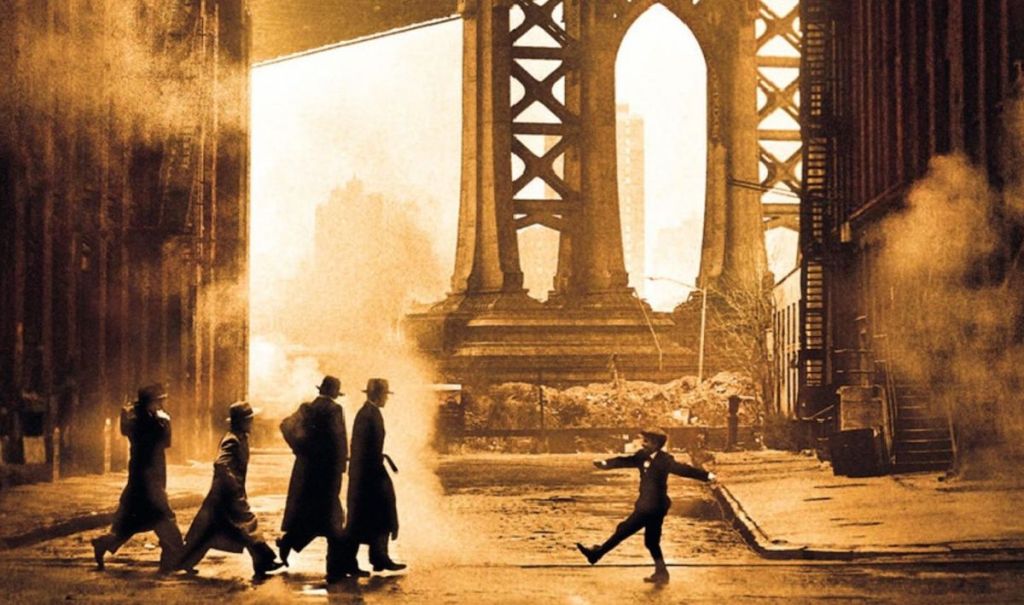

6. Once Upon a Time in America (1984)

Sergio Leone turned down a chance to direct The Godfather to make an unflinching look at the depths of criminal heights. Based on the book The Hoods (1952) by Hershel “Noodles” Goldberg under the alias Harry Grey, the film stars Robert De Niro as David “Noodles” Aaronson and James Woods as Maximilian “Max” Bercovicz. A pairing as exciting as Bogart and Cagney. De Niro is in his prime, gangster film royalty as the veteran of The Gang that Couldn’t Shoot Straight (1971), Mean Streets (1973), and The Godfather, Part II. Woods created one of the most convincing sociopaths of crime cinema in The Onion Field (1979).

Once Upon a Time in America opens with a botched liquor delivery and ends on a wood-chipper grinding a mob mastermind, and still takes the time to savor Charlotte Russe. The film has been called the movie that killed the gangster genre. There are no heroes or anti-heroes. The masks are off, mobsters are monsters.

5. Scarface (1983)

Director Brian De Palma and screenwriter Oliver Stone created the most audacious cinematic gangster in Scarface. From chainsaw massacres, through cocaine mountains, to the unmistakably overreaching accent Al Pacino tosses off with impassioned commitment, Tony Montana’s career is littered with the successes of excess. He learned to speak English by watching Cagney and Bogart movies, and his gangster translation is impeccable.

The arc of Pacino’s Cuban immigrant surpasses that of the Italian arrival in Howard Hawks’ original 1932 film. In exchange for a Green Card, Montana and his friend Manny Ribera (Steven Bauer) assassinate General Emilio Rebenga, who tortured the brother of crime boss Frank Lopez (Robert Loggia). The charming cocaine distributor repays Tony with a job, and a warning which would come back to bite him on the ass: “Never underestimate the other guy’s greed.” The new Scarface exceeds even this. Through it all, we root for Tony Montana, if only because we don’t want to be on his bad side.

4. Mean Streets (1973)

Mean Streets is one of cinema’s most influential films because it is one of the most personal. It feels like a home movie. David Johansen said he thought he was watching a documentary when he first saw it. Mean Streets doesn’t play out on the manicured lawns of The Godfather. These are the day-job enforcers, Goodfellas on a $500,000 budget. Harvey Keitel’s Charlie collects protection money for his uncle Giovanni (Cesare Danova). His friend Johnny Boy (Robert De Niro) can’t scrape together what he owes to loan shark Michael (Richard Romanus) because he owes more money to bigger wise guys.

Charlie could get made if he gets rid of his friends, and his epileptic girlfriend Teresa (Amy Robinson), but his Catholic guilt gets in the way. Johnny Boy’s self-destruction is his penance, Keitel lets De Niro steal the film like he can use it to pay off his character’s debts.

3. Goodfellas (1990)

Ray Liotta’s Henry Hill goes from rags to riches to rat in one of the greatest mob movie arcs. Robert De Niro’s Jimmy Conway is a legend who lives up to every word on the street. Karen Hill probably taught Lorraine Bracco more about mob psychology than all six seasons on The Sopranos. Martin Scorsese put the fun back into crime with his game-changing masterpiece of violence and humor, Goodfellas. The clothes, cash, coke, and clubs are exciting, even when dangerous. The exuberance of Joe Pesci’s Tommy shooting over a car roof during a getaway drive more than offsets any shine-box insults.

“As far back as I can remember, I always wanted to be a gangster,” the film opens, and it touched a nerve. More guys tried to get made after Goodfellas came out than after the commission had to close the books in the aftermath of The Godfather.

2. The Godfather, Part II (1974)

“You broke my heart, Fredo,” Michael Corleone (Al Pacino) sadly informs his younger brother, dutiful son, and inadvertent rat, played by John Cazale, in The Godfather, Part II. Then he breaks all family ties with a kiss of death. The story of the son of Don Vito Corleone is as perilous and exciting as his father’s. We see in Robert De Niro’s young Vito Andolini, an immigrant who passes through Ellis Island with nothing to his name but a price on his head. He takes the name of his Sicilian home town Corleone and becomes a caporegime of industry, leaving a dynasty that ultimately survives all its enemies.

The locations, whether capturing 1950s Las Vegas, New York City at the turn of the century, or the hilly Sicilian villages where young Vito hides, are exquisitely rendered. The score by Carmine Coppola and Nino Rota is a masterpiece. Director Francis Ford Coppola makes an offer no one can refuse: the perfect sequel to the perfect crime movie.

1. The Godfather (1972)

Take away the accolades for changing cinema and claims of best-picture-ever status, and director Francis Ford Coppola’s The Godfather is still the best mob movie ever made. It tells the story of the most successful of the Five Families on the New York Ruling Commission without ever once uttering the word mafia. Just like real mobsters, who would never even mouth it in public. Marlon Brando’s Vito Corleone is the most iconic gangster ever projected on screen, and Al Pacino’s Michael earns his button like no other in cinematic mob history. Sonny (James Caan) might have been a bad don, hotheaded and reckless, but that character epitomizes the gangster allure. Every gangster who made their bones after 1972 wants to be Sonny.

Coppola always saw his adaptation of Mario Puzo’s novel as an indictment of corporate America, and it is cutthroat. No crime movie made violence look more artful. Not many mob movies made food look so good either. The Godfather is known as a family film and it is packed with as much Italian seasoning as it is with Sicilian reasoning. See it now before the vengeance gets cold. Leave the gun, take the cannoli, and don’t stop for tolls.