The joy of discovering a hidden videogame gem

It's fun playing the acclaimed classics, but there's a certain thrill in discovering an old, half-forgotten videogame gem, too...

From the earliest computers to the PCs and consoles of the present, every system has its undisputed classics. The ZX Spectrum had things like Manic Miner, Chaos and Deathchase. The SNES had such games as Super Metroid and Super Mario World. The Amiga? Cannon Fodder, Another World, The Chaos Engine and many more besides.

The sign of a true classic, of course, is that it’s still hugely playable even years after its release – hence the enduring affection for so many of those games mentioned above. But while it’s always worth visiting the medium’s most respected titles, there’s also a certain thrill in roaming further afield and discovering something you’ve never heard of before – much less played.

A case in point: while idly scrolling through eBay on one of those phantom days between Christmas and New Year, I stumbled on an old Japanese NES (or Famicom) game called Hino Tori. The box was a bit battered, but the stunning artwork still shone through; the price was right, and the game was made by Konami, so I promptly purchased the thing.

It was only later that I found out a bit more about this odd-looking game I’d purchased on a whim. Its full name is Hi no Toro Hououhen: Gaou no Bouken, which translates to Phoenix Chronicles: Gaou’s Adventure. Originally launched in 1987, it’s loosely based on a long-running manga series by the godfather of the medium, Osamu Tezuka (even if you’ve never heard of him, you’ll know his most famous creation: Astro Boy).

Hino Tori’s 1987 release places it right in the midst of Konami’s golden age. Around that point, it was busily putting out classic after classic, either in arcades or on home systems like the MSX or Famicom: games like Gradius, Salamander, Contra, Castlevania and the original Metal Gear. Indeed, Konami’s prowess at porting its own games to the NES is one reason why the console was such a hit – as good as Nintendo’s own games were, the system probably wouldn’t have done so well without some decent third-party releases.

Unlike those other games, however, Hino Tori was never released outside Japan – an odd state of affairs, given that even Konami’s lesser games of the period made it to America. Hino Tori may have been based on a manga unknown to westerners, but it could have easily been revised slightly to appeal more to that market. Konami’s action game Mad City, for example, emerged in America with revised graphics and a new title: The Adventures Of Bayou Billy.

It’s possible that Konami decided that Hino Tori was simply too steeped in Japanese folklore and local references to successfully translate – indeed, play through the first level, and you may wonder what the hell’s going on. The central character’s a fairly unlovable-looking chap with a huge nose, long black hair and magenta trousers; he isn’t exactly Super Mario. The rest of the graphics are an acquired taste, too: an odd collection of rocks, snakes and floating heads.

Hino Tori’s one of those games, though, where the unwelcoming front-end belies hidden depths. First, there’s its really novel control system. The hero, Gaou, can defend himself from enemies by throwing spears either straight ahead or vertically – an ability that turns Hino Tori into something approaching a run-and-gunner, although without the ferocious turn of speed found in, say, Contra. Gaou’s other party trick is his ability to create his own platforms – single blocks that he can spawn just about anywhere, thus allowing him to hop to higher levels and gather items.

The only drawback is that Gaou has a finite number of these blocks, though fallen enemies drop new ones, so it’s unusual to run out of them unless you’re really clumsy. The platform-making ability makes Hino Tori quite unlike any other action game of the period, since it adds an element of strategy and puzzle solving – it’s telling that the game even allows you to destroy yourself by hitting select, since it’s possible to trap yourself with your own platforms.

Once you get the hang of the system, however, the platforms become pretty much indispensible, whether you’re using them to dig your way out of a steep-sided pit, reach a high catwalk or even fight an area boss. “Emergent gameplay” wasn’t really a term people were using in the 80s, but Hino Tori undoubtedly features a hint of it – the game’s makers didn’t necessarily expect its players to use the platforms as a means of staying out of a boss’s reach, but it’s a viable tactic if you feel like trying it out.

The only other game of Hino Tori’s vintage with a similar mechanic was Taito’s classic, Rainbow Islands, though it’s likely that Hino Tori beat that game to release by a few weeks or so; Rainbow Islands hit Japanese arcades in 1987, but Hino Tori came out on the 4th January that year. Besides, Hino Tori’s platform-building is rather different from Rainbow Islands’ curved, conveyor-belt like walkways. The emphasis there was more on speed and timing than strategy.

Hino Tori certainly looks less appealing than Rainbow Islands, though even this issue seems to ebb as the game goes on. Oddly, the better-looking levels are tucked away deeper into adventure, as cliffs and caves give way to exotic, sometimes surreal space landscapes and metallic future zones. Where most games of the era front-loaded all their best assets, Hino Tori tucks them away in later stages.

You may be wondering, by now, just what links all these disparate elements. Who is this big-nosed guy we’re controlling? Why do the blocks have angry faces? What’s with all this time travel? It’s here that our research took us down a bit of a rabbit warren.

Gaou’s an unlikely hero, even going by his backstory. He lost an arm and an eye as a youth, and as a grown-up, he killed his wife in the midst of a heated exchange. Filled with remorse, he learns to sculpt from a Buddhist monk, and sets himself the challenge of creating a large statue of a phoenix. The only trouble is, the statue’s broken into 16 equally-sized bits, each stashed in a different time and place in history – and so Gaou hurtles around the world on a quest to track them down.

Those platforms with angry faces, then, are the fruit of Gaou’s sculpting efforts, and the strange blocks you acquire at the end of each stage are the bits of phoenix statue. Collect the lot, and you’ve completed the game.

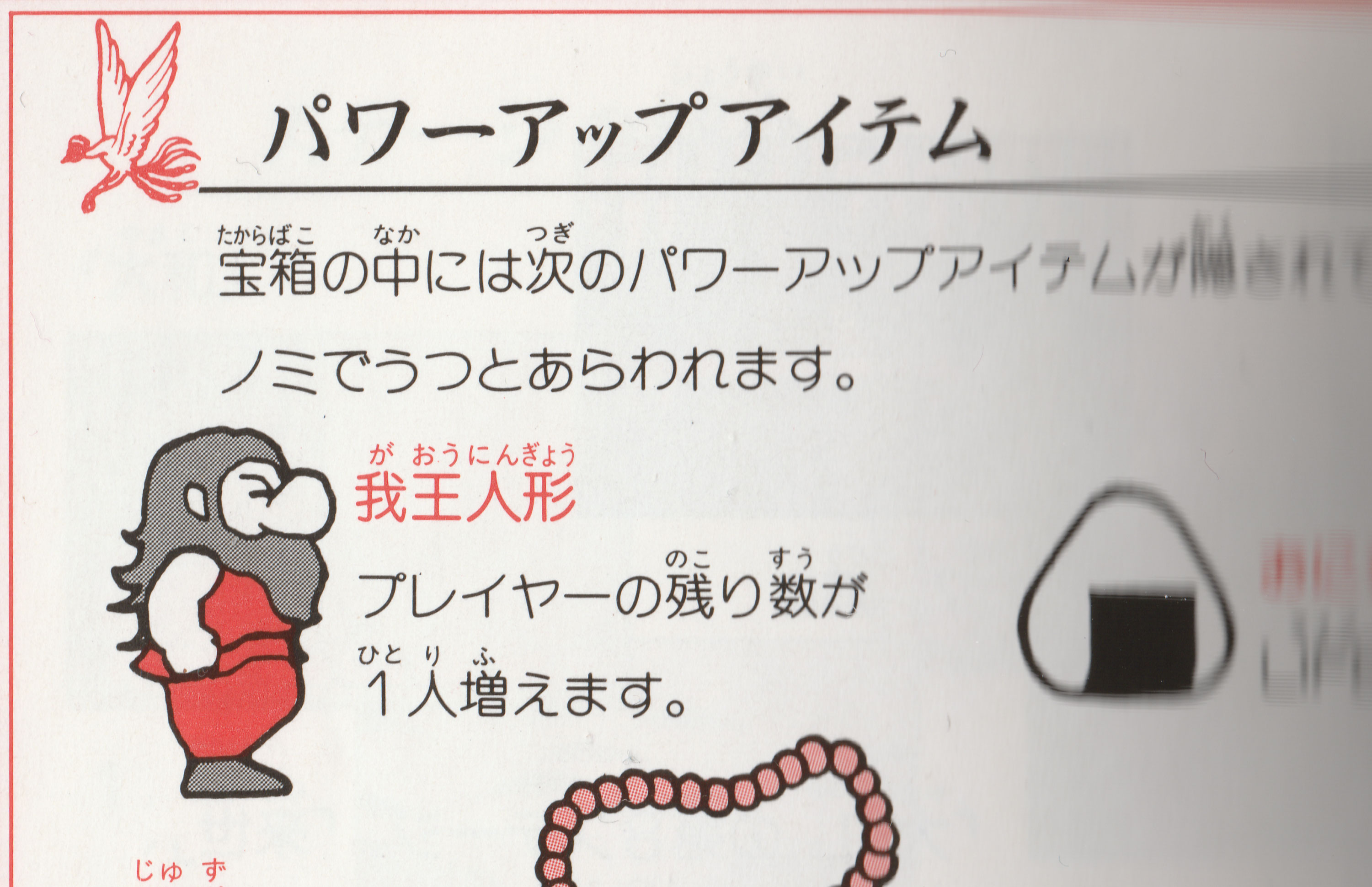

It’s a weird story, certainly, and not entirely faithful to Tezuka’s sprawling source manga, either – though the game’s journey through different time periods, from 9th century Japan to futuristic planets, is straight out of his Phoenix saga. Beyond the basics, you don’t need to know too much more about the manga in any case – though a passing knowledge of Japanese culture may help you recognise some of the collectible items dotted through the game. Those odd triangles that give Gaou extra energy, for example, are onigiri, or rice balls. You can also spot these in some Alex Kidd games.

It’s details like these, we suspect, that would have been lost had Hino Tori been translated for western consoles. It’s certainly difficult to imagine Nintendo of America signing off on a game which stars a reformed murderer as its can-do hero.

Still, Hino Tori‘s quirky touches give it a pleasing air of the exotic, and it’s fair to say that its surreal level designs and enemies are quite unlike anything else on the NES. The game has depth, too, thanks in part to that block-building mechanic, and also the ability to smash up the scenery to find the secrets tucked away beneath. By jumping and then firing downwards, Gaou can dig out treasure chests with useful items inside, or better yet, uncover portals that take him to different time zones. It’s only by finding these portals – which whisk the player back and forth across the various stages – that all the pieces of Phoenix sculpture can be found.

Quite by accident, then, your humble writer stumbled on what might be a half-forgotten classic from Konami’s golden age. Sure, Hino Tori isn’t perfect – its control system is fiddly at first, for one thing – but then, things like Castlevania and Contra had their flaws when viewed without the old nostalgia glasses on. It’s difficult to track down the exact personnel who worked on Hino Tori, but it certainly feels of a piece with some of the great games that Konami was making in the mid-to-late 80s. (The music, part-written by Castlevania‘s Kino Yamashita, is as upbeat and catchy as you would expect.)

Discovering a half-hidden gem like Hino Tori feels a bit like a lazy form of archaeology: you’re idly scrolling through the listings on eBay, or Steam, or an app store somewhere, you take a punt on something you’ve never heard of, and it ultimately pays dividends. Of course, there are all those other times where you might have purchased a game and, within a few minutes, realised you’ve made a dreadful mistake, but even those forgotten hours seem worthwhile when, on those rare days when everything lines up, you stumble on a true hidden gem.