Who Was The Haunting of Hill House Author Shirley Jackson?

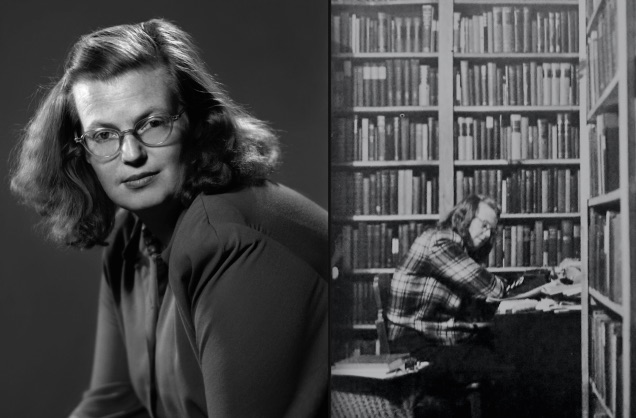

The reclusive subject of the new movie Shirley was a pioneering writer in her time.

In the new film Shirley, Elisabeth Moss plays a fictionalized version of acclaimed author Shirley Jackson, whose two-decade career yielded six published novels, two memoirs, and around 200 short stories. Although her career and life were both uncommonly brief, Jackson’s output has endured and she is one of those rare writers whose work is held in high esteem by both literary critics and horror enthusiasts.

“I think I have always been interested in Shirley Jackson,” says Sarah Gubbins, who adapted the screenplay for Shirley from a novel by Susan Scarf Merrell. “Somebody had asked me that question and I was trying to remember when I first encountered her work. Obviously ‘The Lottery’ was something I read, like many people, in high school. It’s just a story that stays with you. You can’t forget that story.”

While Jackson may not strictly be branded as a “horror writer,” there is no doubt that her most famous works–the novel The Haunting of Hill House and the short story “The Lottery”–had a massive impact on the genre and remain two of its milestones. Much of her other work, while observational and dryly witty, was seated on the border between the real and surreal. It was her deft touch in balancing both, while hinting at outside forces imposing themselves on everyday life that is now considered one of her greatest strengths as a writer, as well as her lasting contribution to the horror genre.

“Shirley was a writer a bit ahead of her time,” muses Gubbins. “I think there’s something that she does, particularly in her novels, which is to explore how terrifying the mundane can be. I think she also explores multiple conflicting psychological quirks… the discomfort in our own safety I think was something that she was really hitting upon.”

Shirley Jackson seemed destined to be a writer. Born in San Francisco on Dec. 14, 1916, she had a relatively affluent childhood in the suburban town of Burlingame but was anything but a “conventional” child: according to biographer Ruth Franklin, she was already spending a significant amount of time alone by the time she was 12, either reading or writing in her room despite her mother’s disapproval. She also harbored an interest in her mother’s pastimes of reading Tarot cards or consulting Ouija boards, leading to her own research in abnormal psychology and the occult.

Jackson was not an especially social person, but she reportedly blossomed when she began attending Syracuse University in 1937, already determined to become a writer and putting herself on a regimen of penning a thousand words a day. She joined a student writing workshop, worked on a literary magazine and published her first short story, “Janice,” which attracted the interest of fellow student and future literary critic Stanley Edgar Hyman.

“There are so many fascinating things about her real life, and it’s very inspiring to learn about the real Shirley,” says Shirley director Josephine Decker. “I don’t even know where to start. I think the thing that the film captures well, which is also in the novel, is just her relationship with her husband was so singular. It was such an unusual romance for that era, and maybe for any era.”

Hyman in many ways mentored Jackson’s career as a writer, introducing her to 18th century English novelists and unfailingly encouraging her natural talents. Disowned initially by their disapproving parents after marrying, the couple lived in New York City, Connecticut, and New Hampshire before finally settling in North Bennington, Vermont where Hyman took a job as a professor of literature at Bennington College while Jackson continued to work on her own writing. She published four stories in The New Yorker in 1943 and another six for the magazine the following year (out of 11 total that appeared in print in 1944), firmly establishing herself as a professional fiction writer.

But the relationship with Hyman was a difficult, unorthodox one, even as they complemented each other in their respective pursuits. “They were so reliant on each other in that artistic realm, yet they had a sex life that was very unusual,” says Decker. “Stanley would go have his affairs and then write long letters detailing every single thing that had happened. He was allowed to have affairs but had to be further than 100 miles from home… Just these bizarre kinds of rules.”

While Shirley is clearly a fictional work–in which a young couple staying with the Hymans become both pawns and collaborators in a psychological war between Stanley and Shirley–it touches on Hyman’s frequent infidelities, many of them with students. The film also opens with the Hymans throwing a well-attended party at their house, something which they reportedly did often. Even as their family grew (Stanley and Shirley ended up having four children, along with a large number of cats and a dog or two), the pair were constant fixtures among Bennington’s literary community, hosting soirees filled with intellectual debate and drinking amidst the couple’s reported library of 25,000 books.

Even as her career prospered, however, Jackson herself began to suffer from feelings of depression, inadequacy, and agoraphobia that only grew as time went on. She eventually became housebound for the last four or five years of her life. She and Stanley also did not get along very well with their neighbors in North Bennington, which could have been at least one inspiration for “The Lottery,” Jackson’s 1948 short story in which a small town enacts a horrifying annual ritual. The story so disturbed readers that The New Yorker received more mail about it than any piece of fiction in the magazine’s history.

Although Jackson published her first novel, The Road Through the Wall, in 1948, she began to explore the dark psychological realms for which she became most famous in her second book, Hangsaman (1951), the writing of which is chronicled in Shirley. In The Bird’s Nest (1954), she wrote about multiple personality disorder, while 1958’s The Sundial focused on an eccentric family who believe the end of the world is nigh.

“Most of her writing was mostly kind of post-war so [there is] that kind of anxiety, the unseen enemy, the ways in which that anxiety is manufactured by the self,” says Gubbins. “I [also] find her very funny. I find her to have a kind of a view of humanity that is not quite satirical because I do think that one of the things about Shirley Jackson is she’s an incredibly empathetic writer, but she loves to explore the vanities and egotism and kind of pettiness of humanity.”

In 1959 Jackson published the novel that remains her most famous: The Haunting of Hill House. It’s about four investigators who set out to explore the titular home and determine whether it is indeed haunted. Jackson’s deft and chilling way with the material and her characters’ psyches–never truly revealing whether the “haunting” is real or not–fashioned the book into a masterpiece that is to this day considered the greatest haunted house story of all time. Stephen King called it in his 1982 book Danse Macabre one of the two “great novels of the supernatural in the last hundred years.”

Hill House was adapted twice as a film, once as a masterpiece of horror cinema in 1963, then again as a disastrous remake in 1999, and was the loose inspiration for a 2018 Netflix limited series. The original book was also a massive influence on later well-known horror novels like King’s The Shining, Richard Matheson’s Hell House, Mark Z. Danielewski’s House of Leaves, and even more recent offerings like Daniel Kehlmann’s You Should Have Left.

Jackson published one more novel–1962’s We Have Always Lived in the Castle–and continued to turn out short stories and other works, but her psychological issues and declining health, combined with prescription drug abuse and increasing consumption of alcohol (also issues touched on in Shirley, although repurposed to earlier in her life), created a spiral from which she was unable to pull herself out. She died in her sleep in 1965 of cardiac arrest. She was just 48 years old and was cremated without a funeral, as per her wishes.

In a tribute published by The Saturday Evening Post, Stanley Hyman (who died five years later) wrote, “Shirley Jackson’s work is among that small body of literature produced in our time that seems apt to survive.” Her work has been re-evaluated by critics in the ensuing decades since her death, with feminist critics especially taking a much closer look at her output. Jackson was not necessarily considered a feminist writer while she was alive and working, which may have contributed to her writing not being appreciated during her lifetime as the landmark body of work it’s now regarded as.

“I think there is a psychology in her work that feels very contemporary,” says Sarah Gubbins. “When I read her work, it doesn’t feel 60 or 80 years old. I think that that’s unusual.” Gubbins adds that while Shirley, the film and novel, are not standard biographies in any way, “I’m really hoping that this film, with the resurgence of some of her other works, is a way for us to go back and really give her due as one of the great American novelists and writers of the 20th century.”

Shirley is available now on Hulu and VOD.