Ready Player One: Biggest Book Changes Made for the Movie

Ready Player One made many changes from the Ernest Cline book, dividing some biggest fans. We examine how and why.

This article contains major Ready Player One spoilers, for both the film and book.

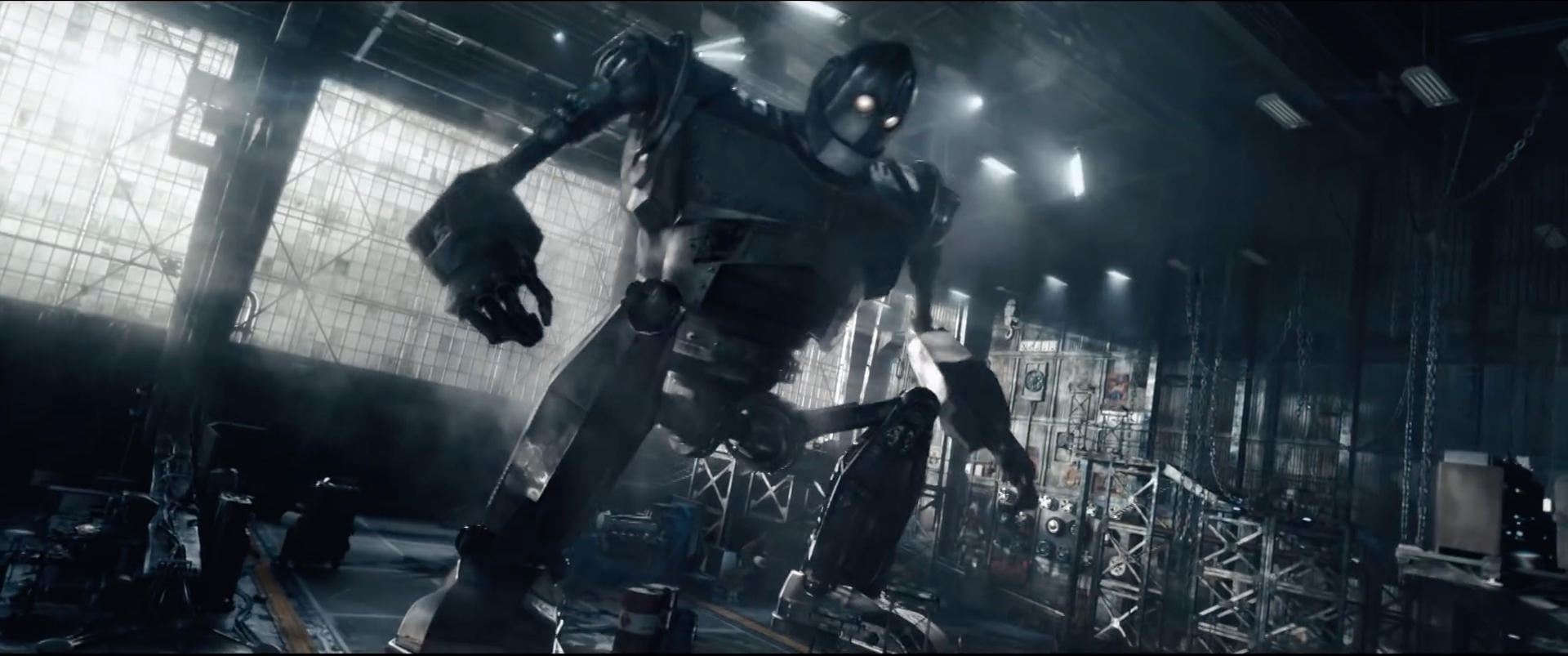

Like so many coins disintegrating across our DeLorean’s windshield, Ready Player One is finally out and consuming movie and geek culture all at once. Steven Spielberg, the proverbial Walt Disney of 1980s entertainment, has made the ultimate love letter to 1980s entertainment, filled with more nostalgic references and easter eggs than a Lego movie, and stuffed to the brim with self-awareness.

Yet this is par for the course for fans of Ernest Cline’s 2011 bestselling novel of the same name, which is far more overwhelming in its member berries than the film can ever hope to be. As perhaps the definitive catalogue of pop culture forget-me-nots for Gen-X, Cline’s literary version is almost a different beast altogether. Unrestrained by copyright limitations, a two-plus hour running time, or a strict adherence for narrative structure as found in the film’s classist director, Cline threw everything into the literary version of Ready Player One. Oh yes, that also includes the kitchen sink, but it’s not just any kitchen sink; it’s the one Michael J. Fox rinsed his hands in during an episode of Family Ties that was shot between Back to the Future movies.

So of course, it was impossible for Spielberg to adapt the full breadth and vision of Cline’s novel, even with the author as one of the film’s credited screenwriters, and ultimately we think that is for the best, including in how Spielberg changed the ending. Even so, it is worth noting the differences between the book and film, and just why the changes might’ve been made, as well as why they nevertheless could be off-putting to Cline’s biggest fans.

However, rather than listing all the individual shifts—which given the sheer volume of homages on Cline’s page would be a fool’s errand—we’ve compiled the biggest changes into the handful of comprehensive categories below.

The Movie Expands On the Type of Pop Culture Referenced

For the formative years he grew up in, Ernest Cline wrote the definitive literary time capsule with Ready Player One. Whereas the film version of the story focuses mostly on popular movies and video games, with some miscellaneous love thrown to the occasional cartoon, anime, or kaiju, Cline misses nothing. Yes, major touchstones like Back to the Future and Street Fighter are featured in both. But the book also has half-forgotten TV shows like Max Headroom, PBS cartoons such as Schoolhouse Rock, and really obscure relics of nerd culture, like the Japanese Spider-Man TV series from the 1970s.

By its nature, the OASIS in the novel is trying to transform the media of the present into the pop culture past of OASIS creator James Halliday’s youth. It also just so happens to be Cline’s youth too. Crucially, one of the most important discoveries of literary Parzival’s journey is found in a recreation of a dimly lit bowling alley/pizza joint with an arcade in the back. It was Halliday’s escape, and it is the tone and tenor of its pop culture interests personified in one place. In contrast, Ready Player One as a movie broadens the expanse of the pop culture landscape being traversed. This is likely done out of a combination of copyright necessity, commercial viability, and simply because Spielberg’s sensibility is larger than the one Cline zeroed in on.

In terms of copyright, it is noticeable that no property owned by Disney or Nintendo is visually featured in spite of numerous mentions. Star Wars, Spider-Man, and Mario Kart get name-checked, but none of them are visually present like Batman, Superman, or Resident Evil. This is likely due to the limits of even Spielberg’s reach in rounding up licenses. Yet the only one that feels like a real missed opportunity is that Cline included the “customizations” he’s made to his own personally owned DeLorean to the one Parzival drives around in the OASIS. Namely, in the book, he tags it with a Ghostbusters logo on each door. While the cinematic DeLorean ride includes the KITT scanner on its grill (which is also in the book), presumably Sony was not as open to sharing its licenses as, say, Universal, who provided Spielberg with the T. Rex from his own Jurassic Park and Peter Jackson’s specific rendering of King Kong.

However, many more of these changes were done to match Spielberg’s sensibilities and that of his broader audience. In the book, Cline and Halliday are obsessed with a specific type of ‘80s culture, such as Parzival’s undying love for Ladyhawke and WarGames. In fact, one of the defining tests (which we’ll expand on later) is based wholly around WarGames, whereas in the film, its closest mirror is when the High Five have a reluctant stay in The Shining’s Overlook Hotel.

Why this is done is worthy of its own article, but suffice it to say that Spielberg has a unique and personal kinship with Stanley Kubrick, which began on the set of The Shining. The movie simply has more resonance for the director than WarGames. However, that also holds true for most audiences too, because The Shining is a major touchstone of pop culture nearly 40 years on, and WarGames is a film that only children of the ‘80s and early ‘90s—or Broderick and Ally Sheedy diehards—will have a faint recollection of.

Due to trying to appeal to a larger audience, Spielberg also expanded upon what pop culture is included. Hence Millennials also see their nostalgia serviced in the movie with Parzival revealing that James Halliday’s favorite shooter video game was 1997’s GoldenEye on the Nintendo 64, and Halliday’s ghost in the machine alter-ego, Anorak, refers to Z at one point as “padawan,” a distinct nod to the Star Wars prequels that current 20-somethings grew up with. And kids today also get a wink and a smile from shotouts to Minecraft, Overwatch, and Halo.

All of this reflects a shrewd commercial choice to expand the pop culture, but it also is subject to a Spielbergian sense of curation. Simply put, his interests lie beyond the pizza parlor/bowling alley arcade, so he also includes more high-brow references to Citizen Kane, with Z saying that Kira is Halliday’s “rosebud,” and having I-R0k quote Frank Capra’s It’s a Wonderful Life to Nolan Sorrento. Intriguingly, Spielberg has also chosen to excise almost all references to his own films. While the book sits fawningly at the feet of Raiders of the Lost Ark, E.T., and the Spielberg-produced Goonies, only the T. Rex from Jurassic Park is given a dramatic showcase, which is curious as she does not appear in the book. He also includes the DeLorean from the Marty McFly movies he produced because it is inseparable from Parzival’s personality. Indeed, the movie leans into the Back to the Future references, while sadly cutting one of Cline’s subtler nods to Spielberg: in the novel Wade Watts calls his journal “the Grail Diary,” a la Sean Connery’s vital notebook in Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade.

The Film Also Wildly Shrinks the Story

Yet perhaps one of the most contentious changes from the book is found in how the movie radically alters the narrative of the piece. To put it simply, Ready Player One has a vast narrative for its brisk 370 pages. Now whether you find this effect charming or unwieldy will depend upon the reader, but it is impossible to film as a two-hour movie. Even so, some of the many changes made to condense this into a coherent narrative are radical. For instance, the novel takes place over nearly a year versus the film passing in seemingly a matter of weeks. As such, readers spend a lot more time in Wade Watts’ changing day-to-day activities, as well as in learning all the intricate world-building within the OASIS.

In this vein, the book begins with Wade still attending his future’s version of high school, which is in actuality a virtual simulation of ‘80s high schools found on the “planet” Ludus, which is only mentioned in passing in the film. While this might seem minor, it becomes pivotal in the book because initially Wade doesn’t have enough in-game currency to leave Ludus, but as the first key (which does not involve a race at all) is hidden on that planet, he is able to find the Copper Key before anyone else. It also creates a more direct comparison between James Halliday and Willy Wonka, as his placement of the first test in the wilds of the free educational planet suggests he wants a child who is in awe of ‘80s pop culture (or magical chocolate) to be who inherits his company.

Other elements of this world-building are far less thought out, such as the rather underwritten revelations about the real world when Wade travels between his hometown of Oklahoma City and Columbus, Ohio. In the book, Wade lives with his aunt on the top floor of the Stacks in another state, but Spielberg wisely excises this mooted detail, as the only significance it has is that Wade (with Parzival money) is able to afford a bus ride between Oklahoma City and Columbus, during which we learn that outside the major cities, the United States has devolved into a Wild West/Mad Max dystopia of complete lawlessness. His bus comes with a security shotgun rider, as if it were a stagecoach circa 1880.

While this is an intriguing development, it has no real importance to the novel, and is in fact somewhat incongruous with the rest of the book, which suggests that corporations now rule a rotten world with an iron fist. The idea that the OASIS is a global, renewable resource when most of its market is a wasteland potentially without power… doesn’t make a whole lot of sense. There are many other such narrative dead ends in the book that are removed from the film, like the character of I-R0k actually being a “friend” of sorts to Parzival and Aech, hanging out in Aech’s basement, which is a popular chatroom for teenage avatars (he doesn’t have a garage in the book). But other than serving a redundant function of revealing on the internet that Parzival and Aech are high schoolers, I-R0k is a character Cline just drops mid-novel without ever revisiting.

Conversely, in the film I-R0k is hilarious comic relief played by T.J. Miller, and who more convincingly serves the function of a character who ruins things for Wade by directly discovering via eavesdropping that Parzival is named Wade, and passing that on to IOI. (Also, I want to note that Spielberg has Wade somewhat more persuasively mourning the death of his aunt, whereas in the novel he takes a nap and then jumps back into the OASIS to flirt with Artemis within 24 hours).

And it is with Artemis that the movie makes its most significant changes, many of them arguably for the best.

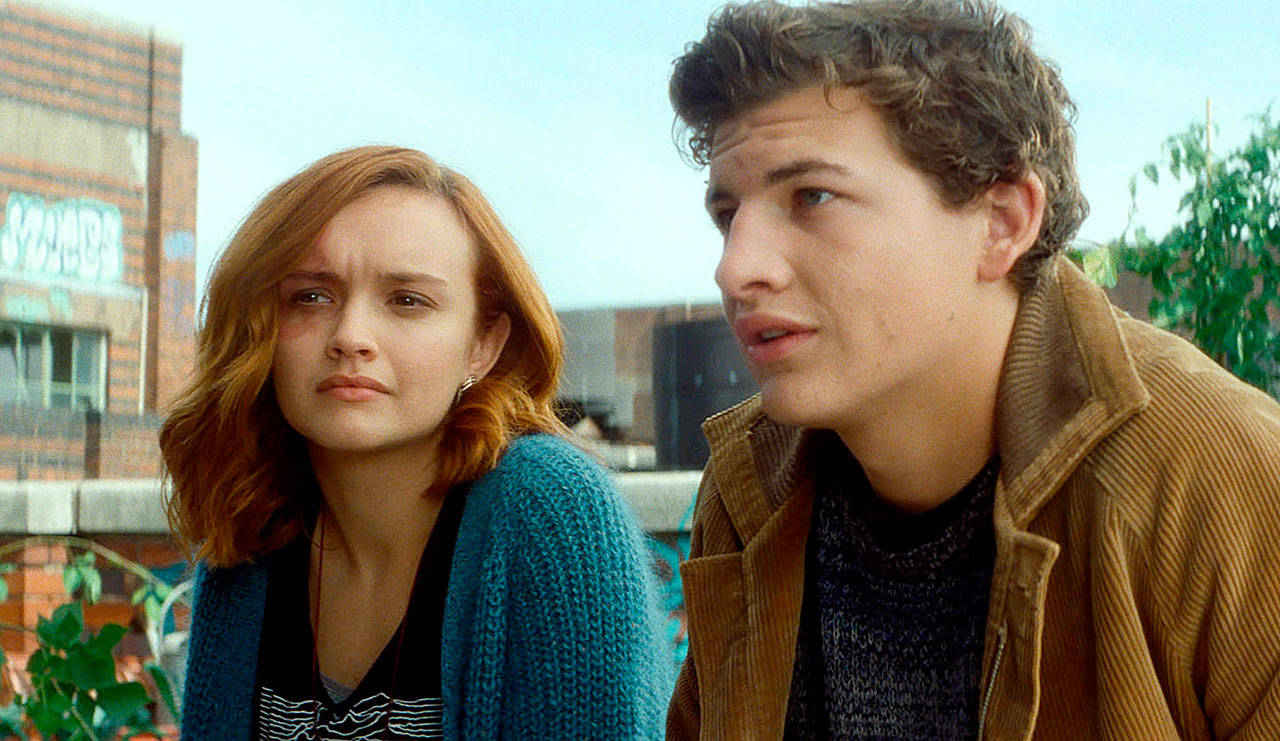

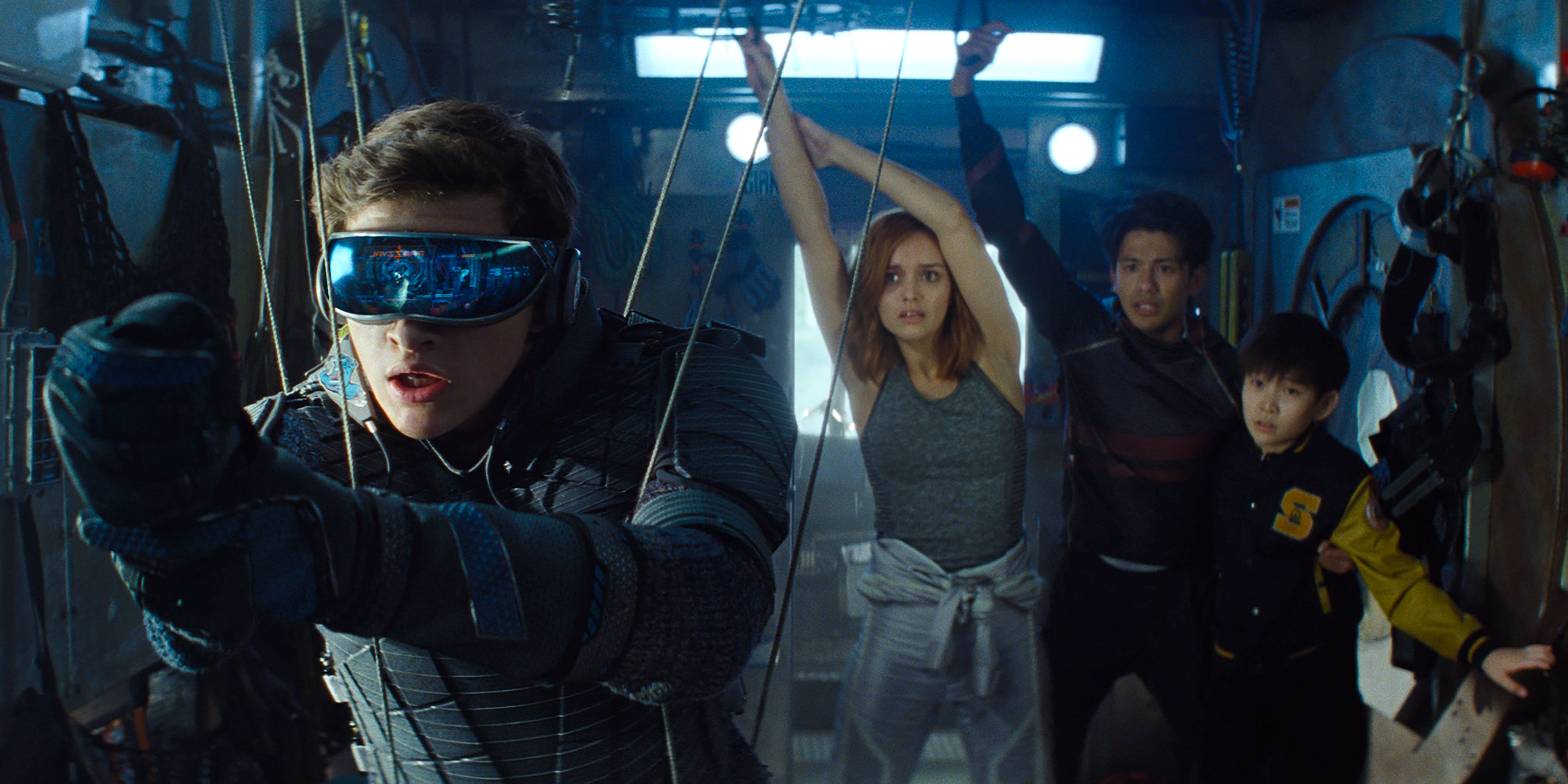

Artemis and Parzival

Again, given that the book spans almost a year versus the film’s compressed timeline, the very nature of Z and Arty’s courtship diverges in wildly different directions, both in the OASIS and otherwise.

It should be noted that during a Q&A at SXSW, Steven Spielberg said it was the charming dialogue and rapport between Z and Arty via OASIS messenger and at the Distracted Globe nightclub that convinced him and his wife he should direct a Ready Player One movie. And he more or less replicates that effect, especially again in the nightclub scene, which occurs earlier in the film than the book, but is more or less the same sequence. The difference, however, is that Artemis and Parzival have been flirting in the book for months by then, whereas in the film that is their third digital meet-up.

This creates a different dynamic when Wade confesses his love to someone who is technically a stranger, although it allows Spielberg to bring them together faster. In the book, Artemis drops out of sight for much of the narrative until the end, blocking Parzival on her email and video feeds, and generally trying to ghost him. In turn, much has been written on the internet about how creepy Wade becomes by messaging Arty every day and spying on all her social media feeds. In many ways, the third act is simply his attempt to “win her back,” even though they were not technically dating.

The film, meanwhile, much more astutely gives Artemis/Samantha a lot more to do than in the book. After Wade loses his aunt, rather than just chilling with Aech and Artemis in the OASIS, we learn Arty is also in Columbus (in the book she lives in Vancouver) and she recruits him to her “resistance.” While it is a bit Hollywood to have a resistance, it gives Artemis a lot more autonomy and agency. The literary Samantha has no backstory other than the birthmark on her face while the cinematic one is going to war with IOI because they essentially enslaved his father and drove him into an early grave.

further reading: The Virtues and Flaws of What Aech Represents

This reason that’s important is two-fold. First, it allows Wade and Samantha to get to know each other in the real world before the obligatory happily ever after kiss at the end. Wade learns about who she is, and she gets to know Wade as a real person when she recruits him to her team, as opposed to being a prize at the end of the novel for Wade to win—like literally, she hides in the center of a hedge maze that replicates the arcade game Adventure, so Wade finds her as his real-life easter egg in the book’s final pages. And that is the first time they meet face-to-face!

While they spend less time together in the OASIS, this change makes their romance feel less like an example of “manic pixie dreamgirl,” and also gives Artemis a major role in the film’s final act. In the book, Wade’s big gesture of love to Arty is to allow himself to be captured by IOI and intentionally go behind-enemy-lines to hack their system and bring down the force field around Anorak’s castle. In the movie, however, it is Artemis who is unwillingly taken by IOI. As opposed to this being the perfect plan of a flawless male protagonist, it is the worst nightmare of a young heroine, who ultimately does much on her own to get out. Z and Daito might hack her out of her slavery-coffin, but it is Samantha who figures out how to bring the force field down and does so on her own accord. Which leads Wade to… the final challenge.

All of the Key Challenges Are Entirely Different

In what is sure to be the least loved change for many literary purists, Steven Spielberg changed every single one of the challenges. Much of this relates to the first point about expanding the nostalgic appeal to a wider audience. Hence while one of the challenges required literary Parzival to prove his uber-geek credentials by knowing each line of dialogue in WarGames, the cinematic counterpoint is an Overlook Hotel sequence that gleefully echoes the spirit of Spielberg’s mentor Stanley Kubrick while not trying to actually recreate any scene verbatim, save for perhaps the beginning of Aech’s Room 237 tryst.

Further though, each of the challenges came in two parts in the book, a key and a gate. As such, Cline is able to double the nerdy credentials of his protagonist. Parzival must first play Halliday’s ghost (dressed as an honest to God Dungeons & Dragons monster) at the arcade game Joust to get the Copper Key, and then must replicate WarGames to get through the Copper Gate. At no point is there a racetrack with King Kong, a creature from 1930s pop culture that likely loomed larger for Spielberg than Cline. Yet ironically, ol’ Kong is more important to most general moviegoers today than Joust or D&D ever will be.

This truth can still be off-putting for fans of the book, as the novel is more low-key about its geeky fun. For example, the ending is not nearly so dramatic as the film. We detailed here all the changes to the ending, but in the broad strokes, the book has no real-world stakes for Wade and friends. They’re all safely hidden away in the mansion of Halliday’s old partner, “Og.” When they fight the epic battle and then finally see Z get Halliday’s egg, there is no threat of IOI attacking. It’s “all a game.” As such, even the game’s stakes are reduced. Once the cataclyst goes off on the page, Wade has a fairly clean path to winning the egg, which includes another arcade game (Tempest) and reenacting all the scenes of another movie (Monty Python and the Holy Grail).

In the film, there is still an arcade game Wade must beat, but he only gets one try (he has near infinite attempts at Tempest), and afterward he is given an Indiana Jones styled test of character by Halliday. If he signs a contract, it is implied he will have forfeited his claim to the egg, kind of like choosing the wrong “grail” in The Last Crusade. That decidedly Spielbergian shift gives a whole lot more resonance to Halliday and Z’s final conversation in his childhood home.

The Movie Downplays the Dark Ugliness of Fan Culture

Finally, while no one will suggest that Cline’s novel thoughtfully deconstructs the toxicity that exists in much of online fan culture, he at least examines the cruelty and loneliness many geeks might feel, and how it can manifest itself in dark ways.

In the book, after Wade’s aunt dies, he ultimately winds up renting an apartment in Columbus. While there is some wish fulfillment here, as he is overweight in the book as opposed to a dashing Tye Sheridan, he can now use his money to have the OASIS force him to exercise in what is a glorified gym membership, losing the pounds fast. But otherwise, it is pretty dark. Wade shuts himself off from the world, blocking out the sunlight of his window with black paint and not going outside for a full six months. He lives only for the internet’s fictional stand-in.

This is never fully explored, as there are no negative repercussions to this unhealthy lifestyle. In fact, he is pretty much rewarded for it by the end. Nonetheless, Cline looks at how people lose themselves in games and virtual distraction, and how gross that can look (in the book, Wade rents a sex doll to sync with the OASIS’ brothels, and pretty much spends a whole week or so paying it undivided attention).

further reading: Ready Player One – James Halliday and His Game are Toxic

Similarly, Daito and Shoto are quite different in the book. While the reader initially is led to believe they’re brothers—and I personally did think one of them was a child, which apparently Spielberg also concluded—it’s revealed they’re not related at all. They’re two lonely adult souls in Japan who have cut themselves off from society, and rely on their families to feed them while they live in a world of pure fantasy and distraction in the OASIS. This is not a dystopic touch either, as Japan’s Labor Department has an actual word for this right now: “Hikikomori.” It refers to people who elect to cut themselves off from society to live like hermits in their anime, manga, and video games. The OASIS would just be the next pop culture opioid.

Hence, the book does give a darker, and some would say more honest, meditation on nerd culture than the almost exclusively celebratory Steven Spielberg movie. And that too is a fair criticism. Yet movies are not books, and books are not movies. By and large, we’d argue the changes made from page to screen benefitted Ready Player One.

Do you agree, players?