1983 Was a Hidden Great Year for Star Trek

40 years ago, the best Star Trek stories weren't being told on screen.

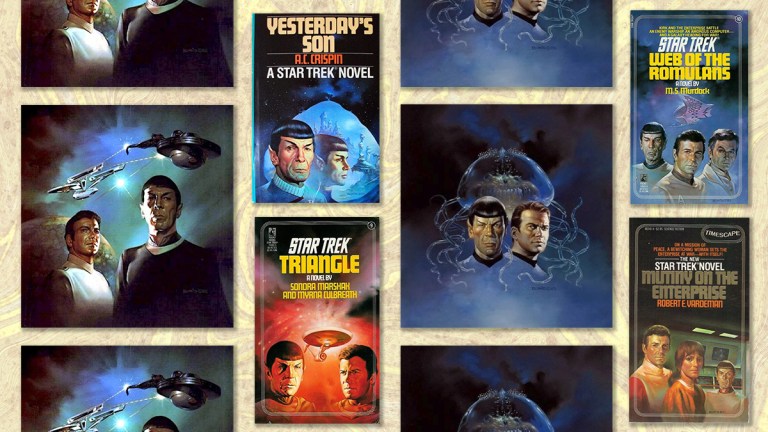

In 1982 Spock died in Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan. But one year later, in 1983, Spock had become a space pirate, helped stop a mutiny on the Enterprise, foiled two Romulan invasions, got locked into a love triangle with Kirk, and, oh, learned about his secret son Zar, via the Guardian of Forever. If you don’t remember any of these thrilling adventures from Star Trek: The Original Series, you might think what is described above constitutes fan fiction, furtively published in the zines of the time. But, you’d be wrong. 1983 saw the publication of six original Star Trek novels, all during a year in which there was not any new Trek on TV or in the movie theaters. It may not be the best year in Star Trek history, but the output was impressive, and proof that Trek’s appeal is far greater than just what we see on screen.

Starting in 1979 the rights to publish officially-licensed Star Trek fiction moved from Bantam to Simon & Schuster, specifically, the imprint known as Pocket Books. The Pocket series began with a series of numbered original Trek adventures, beginning with a novelization of Star Trek: The Motion Picture, written by Gene Roddenberry himself. Today, this book is regarded with bemused curiosity by hardcore fans, or, not thought of at all. In it, Roddenberry asserts that the 23rd century featured some kind of media, a fictionalized version of “Star Trek,” and that he was its author. Captain Kirk was real and had asked a 23rd-century Roddenberry to further put down the adventures of the crew into book form.

Because the ‘79 TMP novelization is so bizarre and apocryphal, it’s tempting to assume that the original novels that followed (zero of which were written by Roddenberry) are equally odd. But, that’s not really the case. What’s remarkable about the run of 1980s Star Trek novels, in general, is their quality and fidelity to feeling like actual episodes of The Original Series, often with a far bigger budget.

Case-in-point, the Sooni Cooper penned novel Black Fire (January 1983), in which Spock goes undercover as a sexy space pirate to try to fool the Romulans. Until the space pirate stuff starts happening, you could squint and imagine this as a TOS episode in the vein of “The Enterprise Incident.” But, the ‘83 Romulan action didn’t end there. In fact, you could say, 1983 was the biggest year for the Romulans ever, considering that they are central to four out of the six books published that year; the aforementioned Black Fire, Web of the Romulans (M. S. Murdock, June 1983), Yesterday’s Son (A.C Crispin, August 1983), and Mutiny on the Enterprise (Robert E. Vardeman, October 1983). At this point, the Romulans had only appeared in three episodes of The Original Series, and three episodes of The Animated Series, and hadn’t appeared in the films at all (although, to be fair, deleted scenes from The Wrath of Khan established Saavik as half-Romulan.) Oddly enough, an early story idea for the film Star Trek III: The Search For Spock would have featured Romulans instead of Klingons as the antagonists. Apparently, the novels published in 1983 reflected something that never came to pass on screen: the Romulans being a bigger deal to the Star Trek stories of the time.

From the perspective of people writing prose Trek stories, this makes a lot of sense. The Romulans are inherently more interesting in the early ‘80s, simply because their culture is more complex than the Klingons at that point in franchise history. Although The Motion Picture reintroduced the Klingons with ridged-foreheads and formidable armor in 1979, none of these new Klingons were characters in 1983. Even in The Original Series, the behavior of Klingons, culturally, was inconsistent.

The Romulans were the opposite: In both TOS and TAS, they’re portrayed as evil Vulcans. So, their association with Spock and the Vulcans instantly creates juicy story opportunities. Meanwhile, the Klingons, prior to 1984, are somewhat generic villains with cool ships. From a certain point of view, the Klingons weren’t really made into a fleshed-out culture until Star Trek: The Next Generation. Even in The Search for Spock, the Klingon Kruge (Christopher Llyod) feels like a criminal and less like the honorable warriors we saw post-1987. The larger point is clear: A more realistic adversary for the Federation in ‘83 was the Romulan Empire.

But, Romulans or not, what makes the Trek novels of 1983 fascinating, is again, their overall quality and consistent ability to feel right at home in the classic TOS pantheon. This doesn’t mean these books are the best Star Trek stories ever, but rather, they feel like a natural outgrowth of the fandom in the ‘70s because they honor the weird mixture of progressivism and regressive sexuality of TOS. In Mutiny on the Enterprise, the crew is beguiled by a pacifist alien woman, who everybody basically falls in love with, which almost leads the ship to its destruction. Kirk thinks all sorts of sexist thoughts about this person, but, just like in an actual episode of TOS, there is a thoughtful introspective theme here all about whether or not the Federation is really a peace-keeping force.

Triangle (March 1983) finds Spock’s pon farr getting triggered outside of the seven-year-cycle, and a love triangle between him, Kirk, and a woman named Sola Thane. Written by Sondra Marshak and Myrna Culbreath, this novel pushes the romantic tensions between Kirk and Spock to the edges of slashfic but not more so than was already implied in The Original Series, or Roddenberry’s TMP book.

The excellent Yesterday’s Son, written by A.C Crispin, gives Spock a son, Zar, the lovechild of Spock and Zarabeth from the TOS episode “All Our Yesterdays.” While it’s hard to imagine the barbarian Vulcan Zar in an episode of TOS, this kind of storyline — in which a child exists retroactively thanks to some time travel action — feels like a precursor to certain ‘90s Trek episodes like the DS9 episode “Time’s Orphan,” in which Molly O’Brien undergoes pretty much the same thing. Plus, the notion of giving Spock a son who lives in a barbaric past is just too good not to put in a book.

Although the cover art from this time makes big use of both the TMP and The Wrath of Khan era uniforms, most of these stories take place during the TOS five-year mission. Ironically, Diane Duane’s The Wounded Sky (published December 1983), features a wonderful cover painted by legendary fantasy artist Boris Vallejo, in which Kirk and Spock are rocking their TOS uniforms, even though this story apparently takes place sometime in 2275, which would put it after the events of The Motion Picture.

This novel, the last of 1983 is also possibly the best of the bunch. Diane Duane wrote several compelling and thoughtful Star Trek novels — including Spock’s World and the Rihannsu series (more Romulans!) — delivering an absolute classic with The Wounded Sky. In it, the Enterprise tests an “inversion drive,” which is supposed to be some kind of improvement on warp drive. But the result is that the crew is hurtled into a spacetime rift, in which various realities seems to merge. Turns out the inversion drive actually rips holes in spacetime, which results in dreams basically coming to life.

Sound familiar? Well, it should. The Wounded Sky was the basis for The Next Generation episode “Where No One Has Gone Before,” which aired just four years later on October 26, 1987, one of the best episodes of TNG’s first season.

Although Star Trek proliferated in the ‘90s more than any other time, the ‘80s were perhaps the time it changed the most. What’s interesting about the snapshot of 1983 is just how similar the Trek vibe was to TOS back then, but how much more potential there was for new adventures. If you’re looking for a time in Trek history when the fiction was fast, readable, and cozily familiar, the early ‘80s are a hidden frontier you can’t miss.