The Failed Video Game Mascots of the 1990s

The video game mascot boom of the 1990s gave us iconic characters and more than a few animals with attitude that failed to move the needle.

Inspired by the record-breaking success of Mario and Sonic, various video game studios throughout the 1990s endeavored to create their own big mascot characters that would certainly become gaming’s next big thing. Many starred in platformers, some represented entire consoles, and others were simply mascot-style characters prominently placed in new titles with only vague hopes of mainstream success. Most of them failed spectacularly.

In those failures, you’ll find lots of laughs, vague memories, and more than a few animals with attitudes left by the roadside. Yet, there are lessons to be learned from those swings and misses. Was the rise and fall of the mascot game a simple case of a bloated market or were larger cultural factors to blame? Were there great games and mascots that got lost along the way? Perhaps most importantly, is there any chance of the mascot movement making a serious comeback in the modern era?

Bonk (1990)

While the first Bonk game (PC Genjin/Bonk’s Adventure) was technically released in Japan in December 1989, Bonk’s ‘90s escapades show how flooded and fragile the market for mascot platformers quickly became during the decade.

After all, Bonk’s Adventure was a very good game. Developed by Factor 5 (Star Wars: Rogue Squadron), it was a more action-driven take on the increasingly popular platformer genre that benefited from genuine style and exceptional gameplay. It was comparable to the better Capcom and Konami titles at the time and went on to define the Turbografx-16: the console Bonk was meant to become a mascot for.

In the end, that was Bonk’s biggest problem. The TurboGrafx-16 had a lot going for it, but it just never caught on in international markets. The original Bonk’s Adventure was soon ported to rival consoles, where it suddenly felt a little less special against so much direct competition. Subsequent sequels in the series (which were developed by other studios) failed to evolve the franchise in meaningful ways. Bonk shows that a good mascot game ultimately didn’t mean much if it wasn’t released on the “right” hardware and properly supported across multiple installments. He’s also a reminder that not every failed video game mascot earned that status by being in terrible games. That’s only true of most of them.

G-Mantle (1990)

While the character G-Mantle first appeared in the 1990 game Blue’s Journey, he is…umm…best known for popping up in some of the earliest and creepiest ads for SNK’s Neo Geo hardware. The mysterious G-Mantle (who, it has been noted, bears a striking resemblance to V from V for Vendetta) soon became the mascot for the hardware itself. SNK even had various employees appear as G-Mantle at promotional events. If, for any reason, you happen to be wondering, that costume apparently smelled truly terrible.

This is a case of the cart being put well in front of the horse when it comes to video game mascots. While G-Mantle appeared in several SNK games, he was meant to be more of a console mascot rather than a video game character. That’s a lovely thought, but at a time when great games were selling more consoles, a character that only made sporadic and unmemorable appearances in games was simply not a draw, especially for one of the most expensive consoles ever made. SNK seemingly aspired to get people to ask “Who is G-Mantle?” before gamers everywhere collectively answered, “Who cares?”

Captain Commando (1991)

As we previously discussed, the Captain Commando character was featured in the marketing material for several Capcom games throughout the ‘80s (most notably, the Megan Man series). In fact, those games were officially part of the “Captain Commando Challenge Series.” Captain Commando himself was essentially positioned as a Nick Fury-like character who Capcom treated as the pillar that united their historic hot streak of incredible new releases. In 1991, Captain Commando would finally get his own video game.

And that is where things went wrong. It’s not that Captain Commando was a bad game. It’s a 1990s Capcom arcade beat-em-up, so it’s actually pretty damn good. It’s just that after so much hype, Capcom put themselves in a classic Poochy situation. There was no way that this mass marketing conglomeration of vaguely cool concepts was going to surpass the cultural impact of Mega Man or the other Capcom characters who we were led to believe were always talking about Captain Commando whenever he wasn’t on-screen. Capcom would later incorporate Captain Commando into the Marvel vs. Capcom series as a surprisingly powerful character, but the damage was more than done. Ole Captain Try-hard is destined to be a curious historical footnote.

Zool (1992)

While Zool wasn’t the only mascot title for the Amiga, this game from Gremlin Graphics was treated as the home computer’s biggest direct competitor to the Marios and Sonics of the world. It was…fine. The lanky Zool lacked the ninjitsu coolness that his teenage turtle counterparts benefited from, but the challenging title was entertaining in its own right and featured a few genuinely clever level design concepts.

Unfortunately, Zool is the tragically perfect representative of the many failed attempts to give PC gaming its own platforming mascot. There were great platformers released on PC platforms during that time, but the whole cutesy mascot thing just never caught on among the PC gaming crowd in the ways developers clearly hoped it would. By the time Doom came out in 1993, games like Zool were practically fossils. It didn’t even help that Zool was sponsored by Chupa Chups: a Spanish sweets company with a logo designed by Salvador Dali. The ‘90s were weird, y’all.

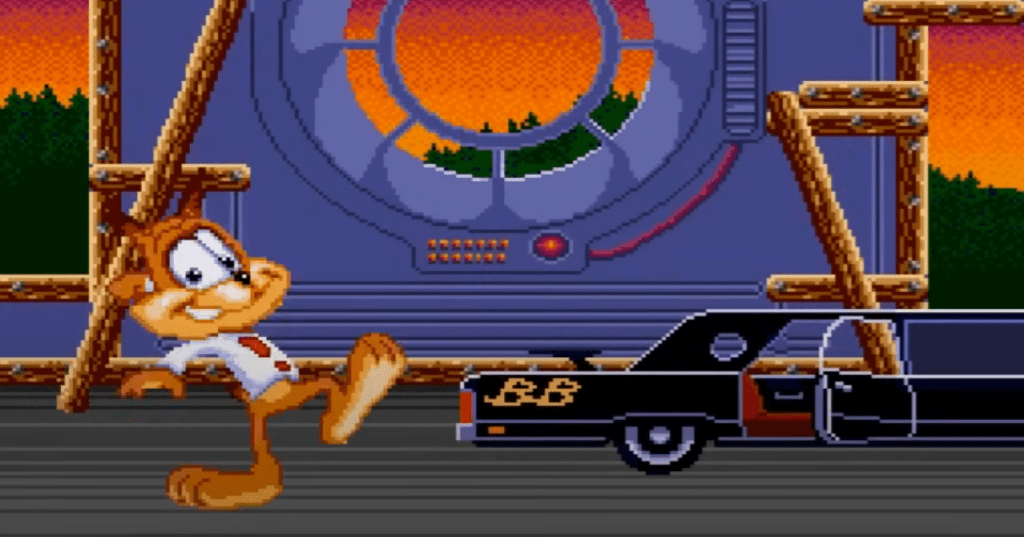

Bubsy (1993)

Bubsy (who made his video game debut in 1993’s Bubsy in Claws Encounters of the Furred Kind) is a strange case of a failed video game mascot. While reviews of that game were largely leaning positive, they ultimately paled in comparison to the hype machine that was the character’s marketing campaign. Bubsy was jammed down the throats of every gamer at that time to the point where some were tired of him before the game itself launched. By the time 1996’s Bubsy 3D secured its status as one of the worst games of all time, many were happy to be rid of the character.

Yet, you could make the argument that Bubsy was something of a success. Not in terms of things like quality or sales but rather as a pure marketing tool. The fact that such a seemingly forgettable character was able to generate enough hype to make his game far more successful than it ever should have been was both a testament to the power of the mascot movement at this time and a precursor to the Taylor Swift phenomenon.

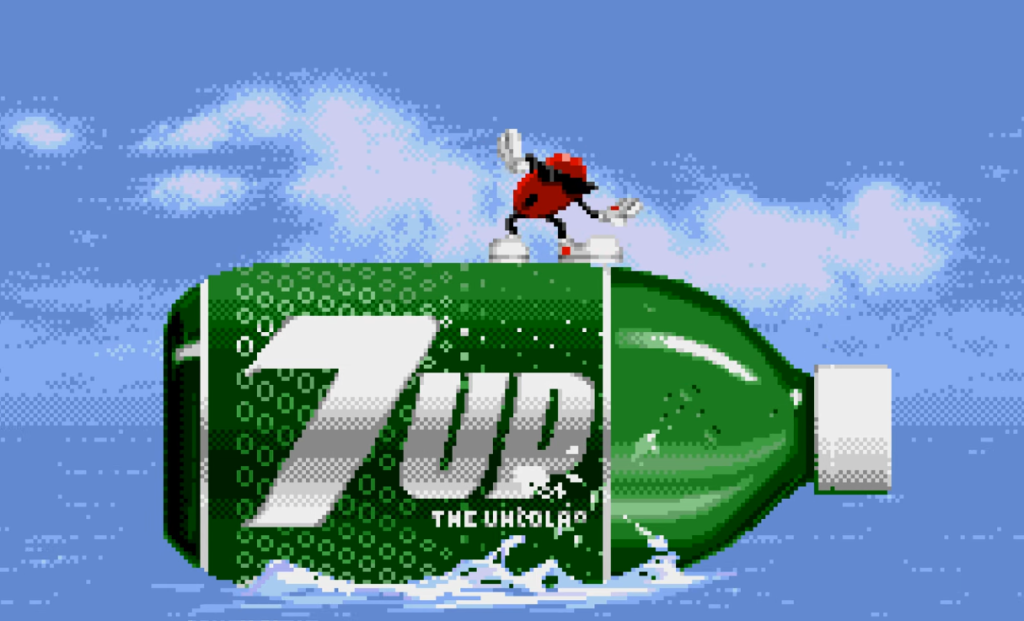

Cool Spot (1993)

Does anything sum up a very particular era of ‘90s culture than the time that the 7-Up company greenlit a video game starring their mascot? Yes, their mascot was just a dot, but it was the coolest dot that ever was and possibly ever will be. Don’t believe me? Then why is it wearing sunglasses? I don’t know what you know about dots, but most dots just don’t do things like that. Such was the overwhelming personality of one Mr. Cool Spot.

Against considerable odds, though, the Cool Spot game is actually pretty ok. “Good” feels like a strong word, but this game has exceeded all known low expectations over the years. Even still, its short-term success was modest and its long-term legacy is slightly better than non-existent. Worse, that title is also both representative of a time when many companies tried to push their own mascot-based video games and a bit of an anomaly in the sense that the vast majority of those titles are as unremarkable as the beige boardrooms they were conceived in.

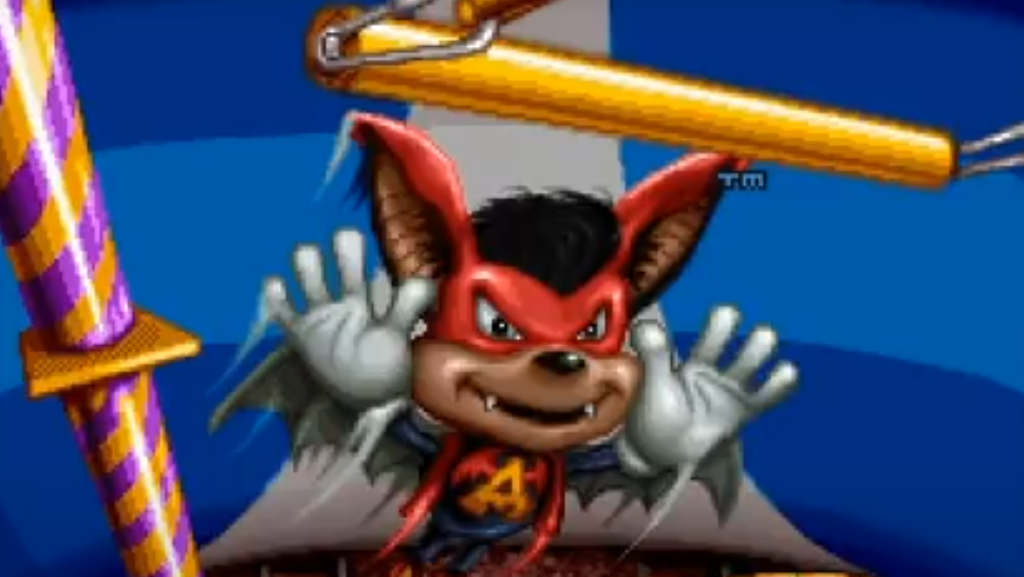

Aero the Acro-Bat (1993)

Despite regularly being fired out of a canon during his day job, the acrobatic Aero never really reached the heights of even some of the lesser video game mascots of the ‘90s. It wasn’t due to a lack of effort, though. Aero’s first two games were solid, as was the series’ only spin-off title, Zero the Kamikaze Squirrel. Try as they might, though, developer Iguana Entertainment couldn’t turn out anything more substantial than “interesting.”

Actually, the name “Iguana Entertainment” is more interesting than Aero in this instance. Aero the Acro-Bat helped Iguana break into the industry, but its failure to achieve true blockbuster status soon softly turned the developer into a sports game studio otherwise best known for its work on the N64 FPS titles Turok and South Park. Aero was never a massive hit, but it was this odd little game that both helped launch a prolific ’90s developer and somewhat sealed their fate as a largely secondary studio. Companies could live, die, or sometimes do a bit of both at the same time by virtue of their mascot creation attempts.

It’s also worth noting that 1993 was a particularly chaotic year for mascot titles. Along with the games already mentioned, you had Awesome Possum, Rocky Rodent, and more all vying for relevancy at that time. Developers spotted a small gap in the release schedule that year and decided to shoot their shots. Many weren’t great and others simply simply got caught in the stampede.

Boogerman (1994)

Boogerman is certainly the embodiment of that Nickelodeon era of the ‘90s when creators everywhere figured out you could reach kids (boys, mostly) by making things vaguely gross and edgy. It could be an effective marketing strategy in the short term, though it was often used to conceal inherently inferior products (as was the case with Boogerman and his Sega CD spiritual equivalent, Wild Woody). As Earthbound showed, that approach could even hurt the perception of a game in the short term. Mind you, it didn’t help that the Boogerman commercial was a live-action monstrosity that tested the limits of the seemingly timeless fart joke.

Gross mascots with limited shock appeal aside, Boogerman also showcases the competition that was brewing between lesser mascot characters at this time. Boogerman developer and publisher Interplay Productions probably didn’t expect him to beat Mario and Sonic, but they clearly had their eyes on the Earthworm Jim series that had achieved considerable second-tier success at that time. Ultimately, Boogerman lost, and Interplay acquired the Earthworm Jim franchise around the time it began its downward slide into total unplayability. It was a brutal time for the mascot gaming, and things were quickly becoming worse.

Ristar (1995)

Ristar has the saddest story to tell at the gathering of failed video game mascots that I assume takes place in one of the smaller conference rooms at an off-the-freeway Best Western. 1995’s Ristar is an incredible game that showcases both the things Sega learned from Sonic the Hedgehog and their willingness to experiment far beyond their perceived comfort zone within that genre. Ristar really should be one of those secondary mascot legends that Sega continuously tried to make happen to give Sonic the supporting stable he desperately needed.

Unfortunately, Ristar had the great misfortune of being released just for the Sega Genesis just a few months before the global release of the Sega Saturn (and after the console had debuted in Japan). On top of that, Sega was fending off increasing (and increasingly overwhelming) competition from Nintendo and Sony. Ristar was born into a world that had determined his fate long before he was given a chance to prove himself.

Polygon Man (1995)

Ahead of the PlayStation’s global debut, the company’s North American representatives started to worry the device wouldn’t appeal to Western audiences. Their solution to this largely manufactured issue was Polygon Man: a giant polygonal head designed to represent the PlayStation brand. The idea was to give the North American launch of PlayStation an “edgy” face, both in terms of Polygon Man’s constant quips about PS1 games and the competition and the literal edges of his design.

The totality of Polygon Man’s failures cannot be overstated. Visceral reactions to the character’s E3 1995 and advertisement appearances revealed that the public not only found him fundamentally disturbing but also a poor representation of the console’s supposedly advanced graphics. Notable design flaws aside, Sony’s Ken Kutaragi suggested that no mascot should be bigger than the Sony brand. That’s a somewhat curious stance given the number of possible PS1 mascots that would emerge, though it’s an idea you can kind of see in the PlayStation brand to this day. In any case, Polygon Man was instantly scrapped and didn’t make another appearance until the release of 2012’s PlayStation All-Stars Battle Royale.

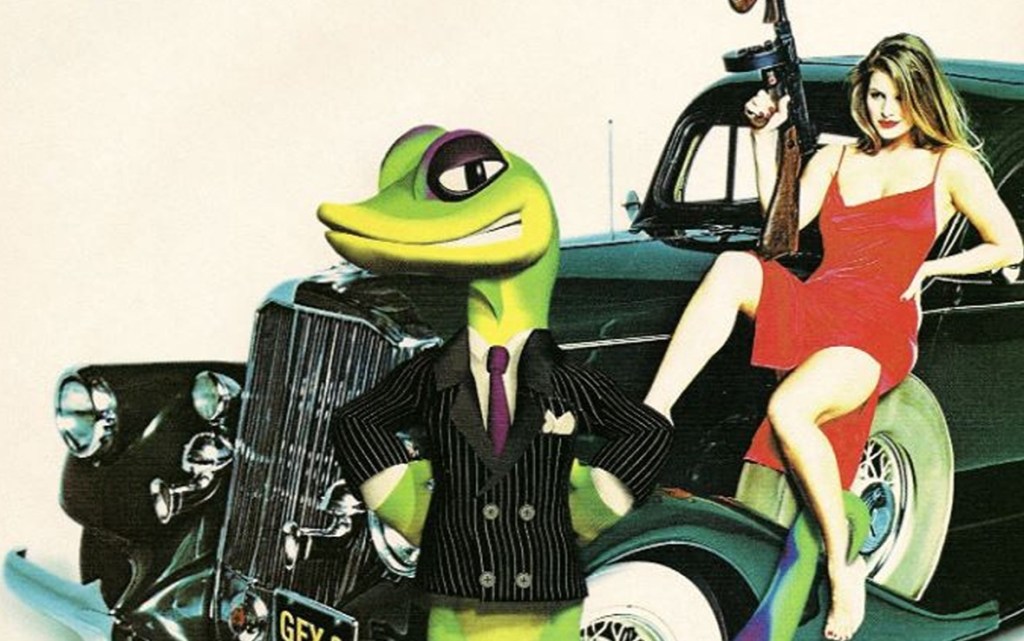

Gex (1995)

If Bubsy isn’t the poster child for the failed gaming mascots of the ‘90s concept, that honor would have to go to Gex. Developer Crystal Dynamics originally intended for Gex to be the 3DO’s biggest mascot. While no mascot could have saved that console from its entirely deserved demise, it didn’t help that Gex’s nightmarish development resulted in a highly flawed platformer. When a version of that game was ported to the PlayStation, though, Gex drew at least cautious praise from those who appreciated the game’s humor, creativity, and style, and those who saw the potential for the franchise to grow into something great.

That never really happened, though. Gex’s humor lent itself well to the magazine ads at the time (including one that famously featured Playboy model Marliece Andrada), but the games themselves continued the original’s spirit by being conceptually clever and fundamentally flawed. Yet, Gex became a kind of icon in his own right. His meta-style humor appealed both ironically and unironically to multiple generations of gamers. For as impressive as Gex’s popularity was, though, the diminishing returns of his games hurt both the long-term prospects of the character and contributed to the growing stigma towards the mascot concept.

Croc (1997)

After a run of hits that notably included Star Fox, developer Argonaut Games decided to pitch a technically and conceptually ambitious 3D Yoshi title to Nintendo. Despite initial enthusiasm on both sides, the deal fell apart. When it did, developer Argonaut decided to go their own way, sever their relationship with Nintendo, and continue working on that prototype. Of course, Yoshi would need to be replaced with a spiritually similar (but legally distinct) reptile known simply as Croc.

The results were mixed. Croc doesn’t break the genre mold, and its borrowed ideas from other N64 platformers often exemplify the slightly derivative design of its lead character. Crucially, though, Croc was released on the PS1; a console notably devoid of N64-like 3D platformers. It stood out on that console and was reportedly one of Argonaut Games’ most financially successful projects. Yet, the relative modern obscurity of the game and the struggles to produce a proper sequel suggested that Croc may have been significantly more impactful in the long run as a Yoshi title. It was a reminder that an elite few mascots had secured their cultural status and that the window for new characters to join that pantheon was either closing or simply already closed.

Segata Sanshiro (1997)

By the end of 1998, the Sega Saturn would be discontinued in the United States and Europe. It was a complete failure for a console that was only three years old in those markets at that point. In Japan, though, the Saturn continued to perform reasonably well. In fact, it performed so well in that region that Sega launched a new, Japan-exclusive ad campaign for the Sega Saturn in 1997 starring the fictional character Segata Sanshiro.

How to describe Segata Sanshiro? In marketing terms, he’s a combination of Chuck Norris memes and the Sneak King. He was a martial arts master who would often appear out of nowhere and beat the ever-loving life out of kids who possessed the audacity required to not be playing Sega Saturn at that moment. Later ads featuring Sanshiro became increasingly unhinged, slightly serialized, and typically showcased a specific Saturn title. They’re some of the best video game ads ever. Seriously, check them out.

The failure in this instance is reserved for the 1998 game, Segata Sanshirō: Shinken Yūgi. What could have been a fantastic comedy action title starring the Saturn mascot was instead an almost WarioWare-like collection of generally awful minigames. It’s a minor failure in the grand scheme of the Saturn, but it was a Saturn game featuring the face of the console was far too little and far too late. Hey, I guess Segata Sanshiro really was the perfect Saturn mascot.

Glover (1998)

Unlike so many of the mascots that preceded it, Glover didn’t try to win people over with a big attitude and bold look. Instead, Glover’s unique design was incorporated into the gameplay. Much of the Glover experience sees you guide a ball to its destination via moves that all feel accurate (relatively speaking) to a mystical glove. Bizarre? My word, yes. But despite its strange set-up and various shortcomings, there was genuine brilliance in this title.

However, that’s also the reason why Glover feels like a sadly appropriate game to end this discussion on. Developer Interactive Studios made a genuine effort to do something more interesting with the mascot concept (specifically within the platformer genre). Yet, Glover didn’t even fail spectacularly; it came and went with little notice in its day except from some critics who seemingly reserved a lot of pent-up vitriol toward mascot platformers for this largely interesting examination of the concept. It was one thing for a mascot to fail on its own merits, but we were reaching a point where indifference or straight-up hostility toward the mascot concept were becoming increasingly common.

The early 2000s saw the influx of mascot games, some of which were certainly better than others. Yet, many of them failed and were ultimately forgotten for similar reasons. A handful of video game mascots had been grandfathered into a new generation. The rest were caught under the wheel of an industry rapidly heading towards a more “mature” era that sometimes felt like the antithetical response to the entire mascot concept. While a mascot worthy of the ‘90s will occasionally make a splash via a Kickstarter campaign or indie title, franchises have simply become a bigger draw than mascots. It’s not that a great game featuring a mascot character couldn’t make a splash but rather that the mascot-lead projects of this era increasingly feel like a relic of their time.