Hamilton: The Real History of the Burr-Hamilton Duel

We examine the actual events that led to Aaron Burr being the damn fool who shot Alexander Hamilton, and just who exactly shot first.

Leading up to the fateful morning of July 11, 1804, Alexander Hamilton and Aaron Burr were incredibly secretive about the rendezvous they’d scheduled in Weekhawken, New Jersey. Only a small circle was aware that the pair, who shared the same banquet table during a Fourth of July dinner earlier that month, were planning to fire pistols in the other’s general direction only a week later. This is because the rules of code duello dictated absolute secrecy—and because dueling was illegal. Yes, even in New Jersey. Hence both parties, like many before them, wrote of this not as a duel or showdown, but as an “interview” of the most urgent nature.

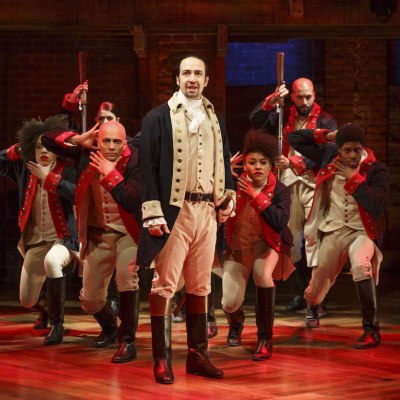

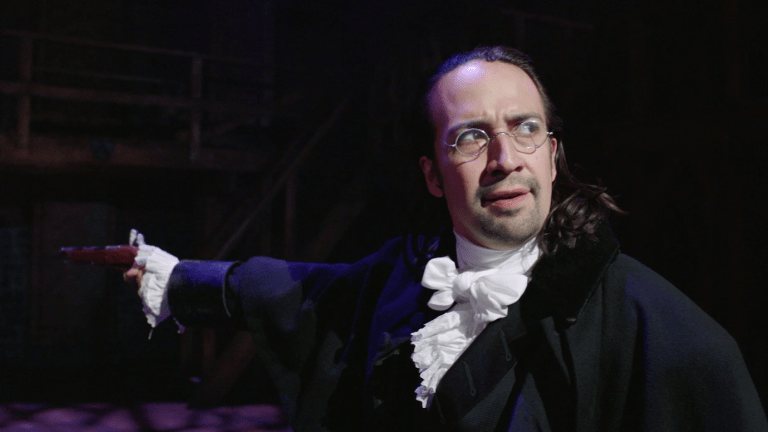

It’s amusing now to think that either man believed deniability could potentially be maintained in an event where two of the leading (if over-the-hill) statesmen of the Revolutionary generation shot at each other from 10 paces! It was an event that historian Henry Adams famously described as “the most dramatic moment in the early politics of the Union,” and one that’s been romanticized again in the 21st century with Lin-Manuel Miranda’s Hamilton. Foreshadowed to the uninitiated during the musical’s very first song when Aaron Burr laments “I’m the damn fool who shot [Hamilton],” the show builds like a grand tragedy to the event. With kinetic energy it dramatizes the special kind of ego it took for two men who were once friends to feel they had no choice but to make their interview on time, and how even though Hamilton was the one who fell, Burr was equally destroyed.

Still, there is much the musical abridges and skips in order to get to that climactic moment, including that it wasn’t even the election of 1800 that directly brought them to that Jersey shore. Indeed, several years, and one more failed political maneuver by Burr, passed before political disagreement gave way to bloodshed. And no less than the fate of the newborn republic hung in the balance… at least as far as Hamilton could see with fears of a New England secession haunting his mind until the night before he threw away his shot. So join us as we examine why the sitting Vice President of the United States essentially murdered the nation’s first U.S. Secretary of Treasury.

A Despicable Inciting Incident

Despicable is a big word with lots of connotations. None of them good. And it proved to be a fatal adjective when Aaron Burr stumbled across the word in a letter written by Dr. Charles Cooper that was published in The Albany Register. Already several months old, the newspaper was passed anonymously to Burr seven weeks after he lost a desperate election to become Governor of New York in the April election of 1804. Still technically Vice President of the United States, Burr was a pariah among the Democratic-Republican Party that controlled the White House and knew the party would drop him in the next presidential election. So, proving ever politically flexible, he’d switched parties and joined Alexander Hamilton’s own failing Federalists in a bid to become a governor.

It didn’t work out, no doubt to Hamilton’s relief. Indeed, the now inciting letter that caught Burr’s attention was penned by Cooper to Philip Schuyler, Hamilton’s father-in-law and former U.S. Senator, in which Cooper insisted a previous letter (one he claimed was published without his consent) did not exaggerate Hamilton’s personal animosity for newly minted Federalist, Aaron Burr.

“I could detail to you a still more despicable opinion which General HAMILTON has expressed of Mr. Burr,” Cooper rather vaguely but unflatteringly wrote about a dinner in February where, if Cooper is to be believed, Hamilton trash talked Burr at length. It wouldn’t be the first time. In fact, as the musical Hamilton underlines, Burr fairly blamed his losing the presidency in the House of Representatives on Hamilton. And they almost came to settling their differences with “an interview” then.

When the U.S. House debated, due to a quirk in the electoral college, if Thomas Jefferson or Burr should be president, Hamilton infamously lobbied for Jefferson, his greatest political rival. Jefferson was “by far not so dangerous a man,” Hamilton wrote. “As to Burr, there is nothing in his favour. His private character is not defended by his most partial friends. He is bankrupt beyond redemption except by the plunder of his country. His public principles have no other spring than his own aggrandizement… If he can he will certainly disturb our institutions to secure his personal power and with it wealth.”

Burr, who famously preferred keeping political disagreements above board, and not personally attacking his opponents, claimed he took such affront that he confronted Hamilton the next year and, perhaps to avoid a potential duel, Hamilton made a tacit retreat.

“He anticipated me by voluntarily coming forward and making apologies and concessions,” Burr said years later. “From delicacy to him and from a sincere desire for peace, I have never mentioned these circumstances, always hoping the generosity of my conduct would have some influence on his.”

It apparently did not. Always brash and determined to speak his mind, Hamilton continued to maintain a dim opinion of Burr, which could only be exacerbated by Burr switching parties to the Federalists at the exact same time a literal plot was afoot among New England members to secede from the nascent union. And far from being a fringe conspiracy, this plan included leaders like Timothy Pickering, who served as U.S. Secretary of War under President George Washington and later Secretary of State for both Washington and President John Adams. After the ascension of Thomas Jefferson and the Democratic-Republicans to the White House, grumbling among New England Federalists began at once with the plan of separating from the United States, and perhaps taking New York with them.

“Tell them from ME, at MY request, for God’s sake to cease these conversations and threatenings about a separation of the Union,” Hamilton wrote to Federalists who floated the idea to him. “It must hang together as long as it can be made to.” Conversely, as Burr switched to the party, he would not repudiate the idea when it was presented. While he also did not agree or make promises to a New York secession if he became governor, his typical political ambiguity on such matters was the kind of fluidity that disgusted Hamilton, and was likely on the mind up until his death. Despite being nine years out of public service after committing political suicide by publishing the Reynolds Pamphlet, Hamilton believed if secession were to come, he’d be required to lead his country again, perhaps even militarily. As he saw it, the fate of the Union was at stake and maintaining his credibility against dangerous forces like Burr was paramount.

On the night before the duel, he wrote with dread about potential secession, “I will here express but one sentiment, which is that the dismemberment of our empire will be a clear sacrifice of great positive advantages without any counterbalancing good.”

Thus hours before he was shot, Hamilton was convinced that the Union was in grave danger from self-serving forces, not unlike Burr, and his honor and leadership would be required. So goes his honor, so goes America. That was at least one reason why he showed up at Weehawken that day, but to get there he first needed to respond to a letter Burr sent him on June 18, 1804. For the once incredibly thick-skinned Burr was now politically ruined and thus susceptible to rage over a single word: He demanded an explanation or disavowal as to why Dr. Cooper characterized Hamilton’s opinion of him as “despicable.”

Preparations

While it cannot be stated with certainty, Hamilton likely knew he was on the path toward an “interview” when he delivered his first response to Burr’s letter. Despite never having fought in a duel himself by 1804, there were six occasions where he came close, three as a “Second” or adviser, as per the rules of code duello, and three times where the advisers were able to cool tensions and get the other man to apologize, as Hamilton was until now ever the challenger. While older Founding Fathers like Jefferson and Adams abhorred duels, and Benjamin Franklin dubbed it a “murderous practice,” it tended to maintain illegal popularity among military officers like Burr and Hamilton who appreciated the violent release of disagreements, and the reward of “satisfaction” in honor reclaimed on the field.

When Burr’s friend William P. Van Ness presented Hamilton with Burr’s demand for a disavowal or apology over the word “despicable,” Hamilton instead offered a multi-page response that both suggests “despicable” is too nebulous a word to explain and that he considered such demands an insult.

“[Despicable] admits of infinite shades, from the very light to the very dark,” Hamilton wrote. “How am I to judge of the degree intended?” He went on to add he rejects, “On principle, to consent to be interrogated as to the justness of inferences, which may be drawn by others, from whatever I have said of a political opponent in the course of a fifteen year competition.” Essentially writing a pedantic argument based on grammatical syntax, Hamilton did a first rate job of intentionally trolling Aaron Burr. He ended the letter by saying, “I trust, on more reflection, you will see the matter in the same light with me. If not, I can only regret the circumstance and must abide the consequences.”

By stating he’s willing to face consequences, Hamilton heavily implied he was prepared for the duel he suspected Burr was angling for. And instead of offering a generic apology for anything he might have said that was misinterpreted, he egged Burr on.

What followed was a week of letters exchanged between Van Ness and the man who would become Hamilton’s Second, Judge Nathaniel Pendleton. (Yes, a New York judge participated in an illegal duel across the Hudson River.) And underscoring the word “despicable” was just the latest umbrage, it reached the point where Burr and Van Ness demanded more than just a disavowal of the word; they now wanted a blanket apology in writing for anything derogative Hamilton might have said, or was rumored or misinterpreted to have said. As there was a paper trail going back years of Hamilton badmouthing Burr, a disavowal would essentially be signing his name to a lie and, in Hamilton’s mind, losing all honor or ability to lead.

So on June 27 Burr cut off further communication and challenged Hamilton to a duel in Weekhawken. But while duels generally were followed at once, the pair would have long days to think about this decision since Hamilton requested a delay. The New York Supreme Court was in session until July 6 and he wanted to ensure he could represent his clients’ interests before the bench. It was a respectable decision that nevertheless led to bizarre moments like the Independence Day dinner at the Society of Cincinnati, a New York organization for retired Revolutionary War officers that Hamilton led.

There Hamilton and Burr, keeping up appearances, sat at the same table on the country’s birthday. Artist John Trumbull later wrote about the night, “Burr contrary to his wont, was silent, gloomy, sour; while Hamilton entered with glee into the gaiety of a convivial party, and even sung an old military song.” In fact, Hamilton’s busy week before the duel included visiting friends and being repeatedly recorded as gleeful, discrediting later some psychologists’ suggestion in the 20th century Hamilton was suicidal. But maybe he was reflective.

On July 3, Hamilton and his wife Eliza hosted in the Granger House “uptown” a dinner party that included William Short, Thomas Jefferson’s former secretary and current protégé, as well as Abigail Adams Smith, the daughter of John Adams. The presence of these heirs to Hamilton’s two greatest political rivals suggested some regret and sudden desire to mend fences with old enemies after his third greatest rival, and once close friend, was now planning to shoot him.

Burr, conversely, kept to himself during these waning days. He wrote his daughter Theodosia and her new husband in South Carolina about how to build a first-rate library, and extracting a promise from her husband that Theodosia be allowed to continue her studies in Latin, Greek, and Classicalism. He likewise amended his will so that his slaves be given to Theodosia (even in death he would not free them).

Yet most significant about these days is Hamilton concluding he would not shoot Burr. Beyond Pendleton, he told old friend Rufus King he intended to throw away his shot by firing above Burr—a rather reckless idea that King tried to dissuade Hamilton of. After all, Hamilton’s own son, Philip, was fatally shot in a duel in Weehawken while attempting to settle a matter gallantly but bloodlessly. Still, the night before the duel, Hamilton wrote for posterity, “I have resolved if our interview is conducted in the usual manner, and it pleases God to give me the opportunity, to reserve and throw away my first fire, and I have thoughts even of reserving my second fire—and thus giving a double opportunity to Col. Burr to pause and reflect.”

The question of how long that pause might have been—and if it occurred—is debated to this day.

The Duel

The overall facts of the duel are meticulously agreed upon—outside of the brief seconds where rounds of lead went flying. On the morning of July 11, 1804, Burr rose from his couch on Richmond Hill and departed with Van Ness to a boat that ferried them across the Hudson. As agreed on with Hamilton’s man Pendleton, Burr would arrive at 6:30am to a small ledge about 20 feet above the water (and far below the more famous plains of Weehawken) to clear bushes and rocks for an isolated dueling location. It was actually quite a popular spot for duelists, including when Philip Hamilton was fatally wounded there some years earlier.

Hamilton and Pendleton arrived closer to the designated time of confrontation at 7am, bringing along with their oarsmen Dr. David Hosack. Normally, two doctors would be expected but it was agreed Hosack would be enough. However, the good doctor and the oarsmen stayed by the boats, so as to have deniability that they saw who shot who. With both men present, Hamilton as the challenged had the right to pick his position. He unwisely selected the northern side of the ledge where he’d have a view of the water, as well as the sun reflecting off of it and into his eyes.

The rules agreed on before Weehawken were clear: The pair would walk at 10 paces, at which point Pendleton would ask if they were ready. Once they agreed, Pendleton would shout “present,” which was the signal they could both fire at will. If one man was to fire before the other, and both were still standing, then the Second of the man who fired his shot would count, “one, two, three, fire.” If the other man still did not fire, he lost his turn. At which point everyone would regroup for a conference to decide if the “obligations of honor” had been satisfied or if there needed to be a second round.

As the challenged, Hamilton had the right to choose the weapons brought to Weehawken. Eerily, they belonged to his brother-in-law John Barker Church, and were both the same guns his son used and that Church used on a separate occasion in a duel against Burr—the greatest injury then being Burr losing a button off his coat. The guns, produced in London, were a gaudy affair of brass barrels and gold mountings. Their extremely large .54-caliber rounds had low accuracy—as any dueling pistol should—but were extremely dangerous in close quarters.

At seven o’clock in the morning, Hamilton and Burr took their positions… but before firing commenced, Hamilton asked for a delay. “Stop,” he said. “In certain states of the light, one requires glasses.” Burr patiently acquiesced. And as his apologists later noted, it gave no indication Hamilton was planning to throw away his shot when he squinted into his eyeglasses and aimed at several imaginary targets, including possibly Burr. The same apologists also like to point out that Hamilton did not tell Burr the guns had a hair trigger. But any suggestion of underhanded intentions is discounted by Pendleton recalling he asked if he should set the hair trigger, and Hamilton responded, “Not this time.”

After Hamilton was satisfied with his vision, the duel commenced. As soon as Pendleton uttered “present,” two shots rang out, as Van Ness, Pendleton, and Hosack attested. How much time elapsed between those gunshots, and who fired first, is a different matter. Nonetheless, it’s agreed Hamilton fell almost instantly after being struck, and Burr’s first reaction was to start toward his former friend. Even Pendleton conceded when he saw Burr walking toward the fallen, he had “an expression of regret.” However, Burr’s Second, Van Ness, would not allow him to reach Hamilton. Rather the oarsmen were approaching. So as to maintain that ever precious deniability, Van Ness rather absurdly to the modern eye was blocking Burr’s vision (and also hiding him from the oarsmen) by opening an umbrella and using it as a shield.

Van Ness ushered Burr back to the water where the victor said, “I must go and speak to him” but Van Ness refused. Meanwhile as soon as Dr. Hosack reached Hamilton, the Treasury secretary is alleged to have said, “This is a mortal wound, doctor” before passing out. For his part, Hosack suspected Hamilton would be dead before they reached Manhattan. That turned out to be inaccurate. Hamilton even regained consciousness on the boat and asked an oarsman to be careful with his pistol, for he believed it to be “still undischarged,” suggesting Hamilton was unaware he fired the gun in the duel.

Upon reaching New York, Hamilton was rushed to friend and loyalist James Baynard’s house. The bullet, as it turns out, had entered two or three inches from his hip, ricocheting through his ribcage, piercing his liver, and finally settling in to the second lumbar vertebra of his spine. He slowly died in Baynard’s mansion over the next 30 hours. At 2pm the next day, he died with Eliza, their seven surviving children, sister-in-law Angelica, and an Episcopal bishop present.

So Who Shot First?

In the musical Hamilton, the events happen very cleanly and unequivocally. Burr fires a split second before Hamilton, who is holding his pistol directly up to the sky. Burr cries out an anguished “wait!” as he realizes too late his rival threw away his shot. It’s a beautiful scene that errs on the Hamiltonian/Pendleton version of events. However, the actual moment was not so clear cut.

Indeed, even before Hamilton died, sympathetic and justifiably angered newspaper editors throughout New York began reshaping the events as pure political assassination. One newspaper said Burr’s silk black suit was crafted in such a way that it was in essence bulletproof. Others claimed Burr was laughing in taverns with friends while Eliza and her children cried over Hamilton’s gasping breaths—supposedly snarking, “I only wish I shot him in the heart.” Others compared Burr to Benedict Arnold. A later wax “recreation” literally depicted it as an ambush, with Burr shooting Hamilton while hiding behind bushes.

For their part, Pendleton and Van Ness initially agreed on the broad strokes in a joint statement released on July 12. There were two shots (not one) with a notable gap of a few seconds, possibly as many as four or five, although they could not agree on the actual amount of time that passed or who shot first.

What emerged as the popular version of events for centuries, and which the musical Hamilton riffs on, was what Pendleton insisted: Burr fired first while Hamilton was already aiming high above Burr. The impact of the shot caused Hamilton to unknowingly fire his gun, shattering a cedar tree above Burr’s head. Pendleton was able to corroborate that last detail the next day when he returned to the scene and discovered a bullet-inflicted branch about 12 feet above where Burr stood and four feet to the side. This version would explain why Hamilton was confused on the boat ride about his pistol still being loaded.

Van Ness, meanwhile, contended Hamilton shot first at Burr and missed. Burr then waited several seconds, as agreed upon in the rules, for Pendleton to begin counting to three. When Pendleton, distracted by his own man, failed to do so, Burr shot Hamilton before he’d lose his turn.

Historian Joseph J. Ellis in his book Founding Brothers: The Revolutionary Generation makes the convincing case that Van Ness’ version has a ring of truth to it, even as it omits that Hamilton fired wide and above Burr. Van Ness did, after all, note he initially was convinced Burr was shot, thinking he saw his man flinch. After the shooting, he ran to Burr (still not knowing of Hamilton’s intention to throw away his shot) and asked “where were you struck,” but Burr explained he was only in pain because he earlier sprained his ankle on the ledge. Ellis further suggests Hamilton was confused on the boat because of possible blood loss and trauma.

Still, the idea that Hamilton fired first and Burr waited to return fire best explains the time elapse of four or five seconds between shots, and suggests Pendleton remembered it differently to better martyr the reputation of Hamilton in case any doubted he intentionally missed Burr. But even if this was the actual order of events, how did Burr not notice that Hamilton missed him by such a berth and why did he still shoot?

No one can know for sure, and after years of having his career thwarted to the point of ruin by Hamilton, Burr may simply have let his rage get the better of him. Ellis contends that it is at least possible Burr might’ve wished to only lightly injure Hamilton. If his bullet was several inches closer to the hip, it would’ve been a flesh wound: and a bullseye on a frequent target in duels, as the hip was not considered a killing shot. However, Ron Chernow, author of Alexander Hamilton, the biography the Hamilton musical is based on, is more unsparing of Burr. He notes only a second or two probably passed between shots. And while Ellis sees Burr insisting they only need one doctor and “even that unnecessary” as a possible sign Burr planned only to mildly injure Hamilton, Chernow’s first assumption is that it was a sign that Burr planned to kill Hamilton instantly on the spot.

While Burr took his exact thoughts to the grave, Chernow heavily implies Burr knew Hamilton threw away his shot. He also cites a story a friend recorded of Burr returning to Weehawken 25 years later. “He heard the ball whistle among the branches and saw the severed twig above his head,” the friend said of Burr. If Burr admitted he heard the ball whistle and saw the severed twig above his head, Chernow suggests this was an unconscious confession on Burr’s part that in the seconds he waited for Pendleton to count down, he realized Hamilton intentionally missed him, and he still shot him anyway.

No one will ever truly know what when through Burr’s head in those seconds before pulling the trigger, but he ruined his life. Within a day, he fled New York and did not stop until he reached Georgia. His political career was even further tarnished and within a year, he seemed to embrace the Benedict Arnold label by pursuing a plot that would’ve broken off a major portion of the Mississippi Delta for himself and Great Britain. It was just one more humiliation and failure in a career for Burr, who lived long enough to hear of his beloved Theodosia drowning after her ship was sunk in the War of 1812.

But then as Hamilton’s version of Burr notes, “History obliterates. And every picture it paints, it paints me in all my mistakes. When Alexander aimed at the sky he may have been the first one to die, but I’m the one who paid for it. I survived but I paid for it.”