What Homicide: New York Left Out About the Carnegie Deli Case

Homicide: New York episode 1 focuses on a city landmark and a sympathetic victim.

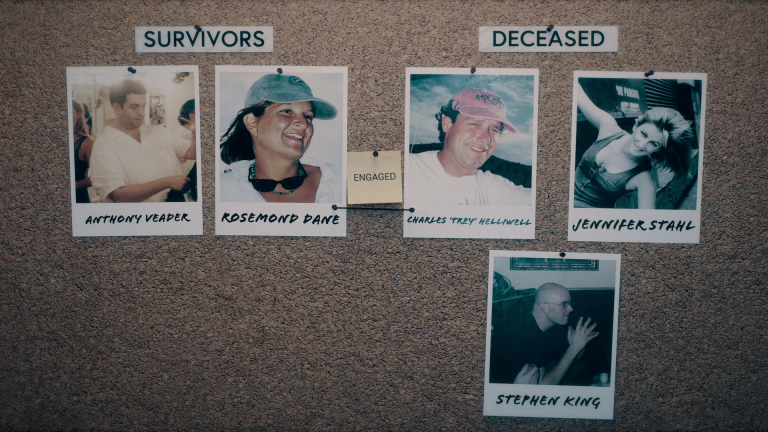

Netflix’s true crime series Homicide: New York’s first installment, “Carnegie Deli Massacre,” opens with the brutal murders of Jennifer Stahl, Charles “Trey” Helliwell, and Stephen King. The episode features NYPD Lieutenant Roger Parrino; Barbara Butcher, the second woman ever hired for the role of Death Investigator in Manhattan; and retired NYPD Det. Irma Rivera. The case plagues these veteran law enforcement professionals enough to revisit the evidence. The deaths seem to have weighed heavily on producer Dick Wolf too. “Tragedy on Rye,” a season 14 episode of his signature show Law & Order, is based on the tragic incident.

The crime also haunted New York. The murders happened on May 10, 2001, during a period when city crime had been on a downswing, and media at the time dredged up fears Times Square would go back to its not-so-distant wild and dangerous earlier character. Like the detectives in the show, it will be a long time before New Yorkers forget the associations. Here are some details the hour-long episode had to trim.

Who Was Jennifer Stahl?

The bodies of the victims were found bound with duct tape and shot in the back of the head, execution style. Helliwell’s fiancée, Rosemond Dane survived the head wound, as did Anthony Veader, Stahl’s hairdresser, who called 911 after the gunmen fled. The owner of the apartment, Stahl, succumbed to wounds in the hospital. Raised in Titusville, N.J., she was an actor best known as the backup dancer in a blue polka-dot dress in Dirty Dancing.

Stahl shifted her focus to songwriting, converting a room into a recording studio where she made music with friends, and dealt high-grade marijuana, also exclusively to friends. Weed was still illegal, and the docuseries points out elaborate precautions. Stahl treated customers like house guests, and promoted her songs, like “Ganja Woman.” She was more than relatable. The May 22, 2001 Village Voice piece “Ganja Woman” ends on the question: “And of course we all wonder: What if I had been there that evening, buying some pot?”

Some essayists pushed back on the victim. On May 12, 2001, Dan Barry of the New York Times published the character assassination “A Fading Actress, a Pile of Drugs and 3 Slayings,” casting Stahl as the rebellious loose cannon aimed at her “’affluent family.’” In the article, Dirty Dancing co-actor Heather Lea Gerdes claims Stahl “sold marijuana for as long as I’ve known her. She felt she had to do everything illegal. She wanted to have fun all the time, but she secretly also wanted to be a star.”

Stahl couldn’t have picked a more perfect home base. It was where the stars aligned over a Zorba the Greek Salad, Milton’s Smorgasbord, or Tongues for the Memory, washed down with Dr. Brown’s cream soda.

What Was the History of the Carnegie Deli?

The scene of the crime was six floors above a beloved New York institution. Located diagonally across the street from Carnegie Hall, Carnegie Deli is a block east of the Ed Sullivan Theater, where The Late Show with David Letterman was taped at the time. In 1984, Woody Allen shot scenes for Broadway Danny Rose, and had a sandwich named for him there. It is mentioned in Adam Sandler’s “Chanukah Song.”

Carnegie Deli was opened in 1937 by Milton Parker, or as he was “lovingly known, The Corned Beef and Pastrami Maven,” according to the sadly-now-closed eatery’s website. It was “an icon for many of the City’s most famous entertainers from Robin Williams, Mel Brooks, and Stevie Wonder early on to celebrities like Stephen Spielberg, Alec Baldwin, and Conan O’Brien decades later.”

The slayings did not happen in the restaurant, though the deli family owns the building, but “the Carnegie Deli Massacre” will always taint the memories of an unofficial New York entertainment capitol.

An Unthinkable Home Invasion

The shootings were an uneasy fit to standard criminal patterns. The arriving unit was concerned about gangland involvement. While there was never as much violence in illegal pot sales as the crack wars, marijuana turf-related shootings were on the rise – though they were routinely street-level and grossly underreported, according to The New York Times. Stahl’s boutique showroom was unique and well above the curb.

According to AP writer Samuel Maull’s “Jurors Get Crime Scene Details in Carnegie Deli Murder Case,” run in the Cape Cod Times, “[Det. Robert] Dunne’s photos showed large color-coded charts that were menus for varieties of marijuana and their prices. He said Stahl also had an album-like book with samples of different kinds of pot. A small sign photographed by Dunne read, ‘Closed Mondays.’” Stahl was drinking wine when the guest-list-approved assailants arrived.

“They didn’t break in, the door’s not broken down,” Butcher recalls in Homicide: New York. Working at the apartment, Stephen King, a musician and health-club manager from Manhattan, was manning the door. He apparently didn’t see the suspects as strangers. He recognized them as customers, even calling out one’s name. This confirmed the assailants were known. Their intent was not. “Don’t hurt anyone,” Jennifer yelled while being dragged, according to Homicide: New York. “Take everything and leave.”

Salley and Smith fled the apartment with $800-$1,000, depending on different reports, and a half-pound of marijuana. A photo exhibited at the trial “showed a black, hard-sided suitcase that Dunne said contained marijuana and cash, and apparently had been overlooked and left behind by the killers when they fled.” The police said “an additional six pounds of marijuana and $1,800 in cash had been more in the apartment,” the New York Times wrote on May 23, 2001.

Examiners lifted palm prints and fingerprints from the duct tape binding the victims. Two suspects were recorded on the second-floor landing surveillance camera at 7:27 p.m., the episode reveals. Eventually, they were identified as Andre Smith and Sean Salley, 29. Smith turned himself in two weeks after the shooting.

Who Was Andre “Dre” Smith?

“Andre Smith stonewalled for more than a day,” according to Larry Celona’s “Inside Carnegie Hell; Suspect’s Gory Tale Of Coldblooded Slay,” cracked when cops told him his fingerprints matched a print lifted from duct tape on the victims. Smith told cops he met Salley in Newark, N.J. two days before the fatal robbery. Smith said he turned down Salley’s suggestion of pulling a robbery. Salley returned two days later with details. “’It’s a white girl who deals weed to a lot of people in the music industry. He said it’ll be easy, no trouble, no weapon,’ the suspect told cops. ‘There’s no guard – we’ll be in and out.’”

Smith confessed he heard a gunshot, and saw Stahl on the floor of the studio. After exiting with the take and driving back to Newark, Smith claimed Salley said killing Stahl “’was an accident,’”according the New York Post’s source. When Smith asked “Why’d you shoot the other four?” Salley explained, “They knew me.”

At his arraignment in Manhattan Criminal Court, Smith was charged with three counts of second-degree murder, and one count each of robbery in the first- and second-degree. Judge Donna Recant ordered Smith held without bail, and placed under suicide watch. After the confession became known, Police Commissioner Bernard Kerik sent a message to Salley in a press conference: “Follow Andre Smith and surrender to the nearest police station.”

Who Was Sean Salley?

Salley knew Stahl from his time in the music industry. “One investigator said Mr. Salley had worked for George Clinton of the Parliament-Funkadelic performing troupe, also known as the P-Funk All-Stars,” New York Times reporter William K. Rashbaum wrote in “Police Identify a Suspect, 19, In 3 Killings at Carnegie Deli.” Clinton’s tour manager, Dana Pennington, said Salley was fired “about a year and a half ago” for allegedly hitting a woman on a band tour bus.

After the Carnegie Deli Massacre, Salley went on the lam outside New York and New Jersey jurisdiction. The detectives successfully pitched the fugitive’s story to America’s Most Wanted, a nationwide platform, and calls flooded in from all over the country. After taking a bus from New York, Salley was tracked to New Orleans. He was arrested in Miami, near a homeless shelter a witness placed him at.

As the documentary points out, Rivera was assigned to travel to Miami to interrogate Salley. He admitted intent to rob Stahl, but resolutely maintained his gun went off accidentally, and claimed Smith killed the other two victims. Salley was arraigned on Aug. 3, 2001.

What Happened During the Trial?

The Twin Towers attack delayed the trial to June 2002. Salley and Smith, held separately in the State Supreme Court in Manhattan, blamed each other for the murders. This necessitated separate trials. The two separate simultaneous trials were held in one courtroom. State Supreme Court Justice Carol Berkman seated two juries, each deciding the fate of a different defendant, in the same courtroom at the same time. Jury selection for the trials began on April 29, 2002.

The State Supreme Court courtroom had its share of drama. Survivors Dane and Veader relived painful details. Salley testified he lied in his statements to authorities because he was frightened of the other suspect and of the detectives investigating the murders, according to New York Times’ Susan Saulny June 11, 2002, report “Suspect in Murders Above Deli Says He Lied in Police Tape.” It was a complete reversal.

On the police videotape, Salley is heard saying Smith “planned a strong-arm robbery for money and the marijuana.” Salley testified that Smith “pulled a gun on him as they climbed to the top-floor apartment on May 10, 2001, and that Mr. Smith demanded he take part in a more violent robbery.” Smith said he gave the original version because a detective told him he was too poor for a good lawyer.

Each jury deliberated for two days. On June 2, 2002, because it could never be proven beyond a reasonable doubt who fired the gun, both Smith and Salley were convicted of three counts of second-degree murder, one conviction each for the deaths of Helliwell, King, and Stahl. On July 30, Smith and Salley were sentenced to three consecutive terms of 25 years-to-life, or about 120 years, in prison without parole.

Homicide: New York is now streaming on Netflix.